A version of this post had appeared in the now-discontinued blog Baraza in October 2014

Visitors have fallen in love with Istanbul for generations. In the early 20th century, photographers captured its blue seas, red roofs, and beige buildings. Despite its beauty, the city’s riot of color obscures a troubling past of missing signs, sounds, and scripts.

Listen closely. The sounds of Turkish give voice to its history. Its raised and rhymed vowels connect the syllables of each word in a harmonious flow, but that flow has been artificially enhanced. During the creation of the modern Turkish state, authorities purged the fricative sounds like “gh” and “kh” found in Arabic and Persian. For instance, in Ottoman words like “yogurt” (Turkish: ‘yoğurt’) were pronounced “yo-ghurt” (with the “gh” sound of the English interjection “ugh!”), but in modern Turkish the “gh” was silenced, becoming “yo-urt.”

The sounds of Turkish resonate with me because I grew up hearing Western Armenian. Our Armenian shares the softer, raised vowels of Turkish, along with a sing-songy, tap-dance cadence. When I moved to Istanbul after college, I was, without knowing it, already an expert on Turkish vocabulary for foods, terms of endearment, and insults. Whenever my grandmother cooked me ‘mantı’ (mini soup dumplings), called me yavrum (“my child”), or yelled dangalak (“idiot”) at another driver, she was inadvertently teaching me words for my years in Turkey. The Turkish and Armenian languages share words for food, love, and hate, but, unfortunately, it is still hate that dominates the relationship between Turks and Armenians. Entire books (and careers) have been devoted to studying the end of the multi-ethnic, multi-confessional Ottoman Empire and its brutal transition to a Turkish nation-state, so I will not elaborate here.

This period of murder and violent expulsion acted like a giant linguistic sieve, straining out “foreign” words. Around 1930, the Turkish state began creating a new language, modern Turkish. Unlike the Ottoman language, modern Turkish shunned the Arabic alphabet, replacing flowing curves and dots with their upright Latin counterparts. Thus فنجان became fincan (“cup”) and چاى became ‘çay’ (“tea”). Authorities also expelled hundreds (if not thousands) of Arabic and Persian loan words, concocting “pure” Turkish replacements in their stead. “Oriental” sounds were also on the chopping block. The fricative letter ‘khe’ (خ, pronounced like the “ch” in “Bach”) became a simple “h”, and another fricative letter, ‘ghayn’ (غ), changed from “gh” to a silent “ğ” (pronounced like the “gh” in the word neighbor). Thus, “yo-ghurt” became “yo-urt.”

As modern Turkish developed, a movement grew around eliminating non-Turkish languages from public life. People speaking Greek, Armenian, Ladino, Arabic, or other languages faced discrimination, beatings, and fines. The movement, started by students and supported by the government, coalesced around many slogans, the most famous of which was “Vatandaş, Türkçe konuş!” (“Citizen, speak Turkish!”)

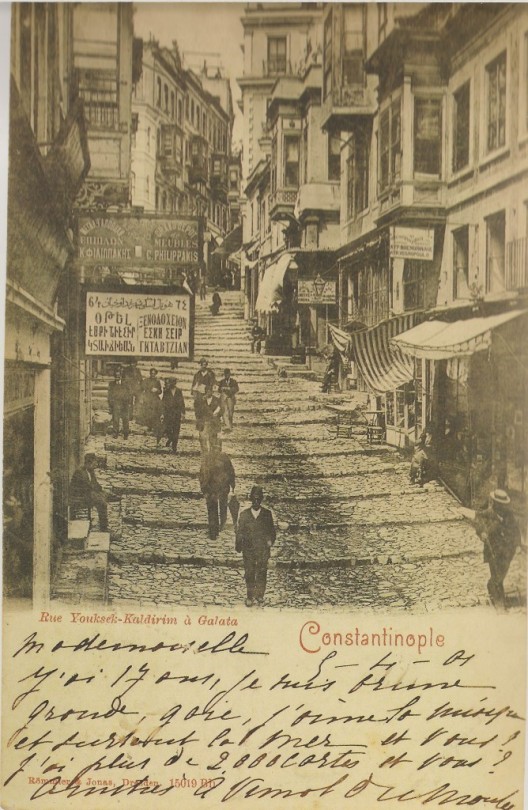

Looking at images from before this period and comparing them with images from today, we can see how effective this campaign has been. Thanks to the photo collection of Orlando Carlo Calumeno, a wealthy and eccentric businessman in Turkey, we have a wealth of such images. Calumeno has collected thousands of postcards which give us a glimpse of what the Empire looked like in the years before the linguistic rupture. In 2005, a book of his postcards was released. Titled ‘100 Yıl Önce Türkiye’de Ermeniler (Armenians in Turkey 100 Years Ago)’, it contains a collection of hundreds of photographs capturing Ottoman Armenian life before 1915. A second volume was released in 2013. In addition to showing us images of Ottoman Armenian life, the postcards also provide a glimpse of Ottoman Istanbul’s linguistic diversity:

The postcard above is from 1901. The neighborhood, called Galata, rises over the Golden Horn, an inlet splitting Old City from the rest of European Istanbul. Galata was a bastion of diversity, where non-Muslim communities like Jews, Greeks, and Armenians lived among the embassies of major European powers. Correspondingly, the storefronts in the postcard offer us information in several languages – Armenian, English, French, Greek, and of course Ottoman.

Elsewhere in the city as well, it was commonplace for the streets to offer passersby a view of several languages. The “Chicago” grocer pictured below shows us a combination of Greek, Armenian, and English:

Today, only the most diligent of tourists in Istanbul would be able to find the traces of these vanishing minority letters. The point never resonated with me until I visited the church of Surp Hıreşdagabed (Սուրբ Հրեշտակապետ, “Holy Archangel”) in Balat, a neighborhood of narrow cobblestone streets and old Greek houses. Just across the Golden Horn from Galata, Balat was home to the noble Phanariot families, Greeks who spent centuries in some of the Imperial administration’s highest posts. A plaque offers some history about Surp Hıreşdagabed Church.

A century earlier, I could have walked by the most mundane locations, grocers and hardware stores, spelling their signs in five different languages. Armenian, like Greek and Ladino, was a permanent fixture in the aural and visual landscape. But the streets have changed. Today, the most prominent signs of this past cosmopolitanism are preserved in glimpses on imperial postcards.