According to Kirchberg and Tröndle (2012), in German speaking countries as well as in the Anglo-American world, the majority of studies on visitor behavior in museums are still heavily theoretical (p. 435-436). On the other hand, as a field with great potential for innovation and interdisciplinary collaboration, studies in exhibition design place a much greater emphasis on the visitor as the main focus of empirical research. Reviewing various studies in exhibition design in his article titled “Interconnecting: museum visiting and exhibition design” (2007), Macdonald says: “Within a more ‘interpretative paradigm’, however, design is recognised more fully as an integral part of the visitor experience, with potentially more far- reaching implications for structuring the very nature of that experience rather than simply providing a more or less attractive medium for presenting content” (p. 150). He also identifies a growing scholarly interest in constructivist approaches, an increase in the use of visitor surveys and semi-structured open- ended interviews in museum spaces that allow us to identify the visitors’ more subjective and emotional reactions as well (p. 151-152). He also adds that “research on particular museum technologies—for example, labels or hand-sets—is a significant, and growing dimension of this kind of research” (Ibid.).

The more recent scholarly approaches not only place more emphasis on the visitor but also attribute him a more active role. Macdonald (2007) argues that research in this realm has begun to rely more heavily on the idea of an active visitor as well (p. 150), and that exhibition designs are abandoning the didactic presentation method in favor of a more interactive approach (p. 153). Blackman (2016) explains that contemporary audiences shall be referred to as ‘prosumers’, i.e. both the producers and the consumers of meanings (p. 37-38). In describing an exhibition in one of her articles, Mieke Bal says that “meaning was not offered to the audience simply to be consumed, but created by and within each individual visitor as they wandered through the spaces” (2012, p. 183).

Another important development is the recognition of the correlation between visitor involvement and exhibition effectiveness. Jun & Lee (2014) cite Simon (2010) to support the argument that participation in the exhibition creation process makes the visitor feel more empowered and attribute deeper meanings to the exhibiting institution (p. 248). For Blackman (2016), “the success or efficacy of the material-semiotic- affective apparatus depends on what qualities, sensitivities and intensities are actively recruited” (p. 51). For Macdonald (2007), “how people negotiate their way through museums and galleries can have considerable implications for how they relate to and interpret exhibition content” (p. 157).

All these three developments, i.e. the growing importance of the visitor, the visitor’s more active role and its correlation to the exhibition’s level of impact, can be observed in the design approach of the exhibition “ON THE FRINGE: The Istanbul Land Walls” (19.10.2016-02.01.2017 extended to 08.01.2017) taking place at Koç University Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations in Beyoğlu, Istanbul. This paper examines its design principles in detail both through in-situ observation and interview with the curator, and tests, via visitor surveys, to what extent the desired impact was obtained.

B.THE EXHIBITION: “ON THE FRINGE: THE ISTANBUL LAND WALLS”

B.1. Before Entering the Exhibition Hall: Preparing the Audience

Curated by Assoc. Prof. Figen Kıvılcım Çorakbaş from Anadolu University Faculty of Architecture and Design, the exhibition presents a comprehensive account of Istanbul land walls and explores the “multi-layered cultural landscapes surrounding them”1. In her YouTube interview, Çorakbaş explains that the exhibition focuses on the land walls’ both tangible and intangible meanings outside of their war context, and adopts a holistic approach towards the subject (2016). She also adds that the exhibition does not intend to replace the actual experience of a visit to the walls; instead, it aims at encouraging one (Ibid.).

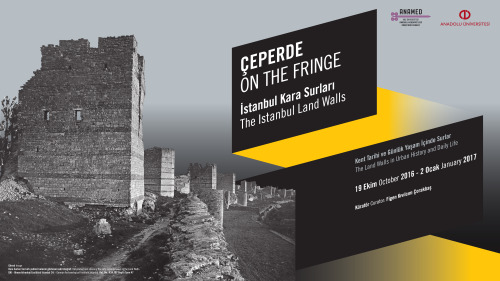

Picture 1: Exhibiton poster

The message in the exhibition poster (Picture 1) is as clear as Çorakbaş’s statement: the depth and rhythm of the land walls in timeless black and white selected as the main PR image supports the message in the introductory text published on the exhibition’s official website, emphasizing “depth” and “multilayeredness”. The exhibition’s subtitle, “The Land Walls in Urban History and Daily Life” is also highly explanatory, communicating the exhibition’s main intention of juxtaposing the experience of the past with that of the present (Ibid.).

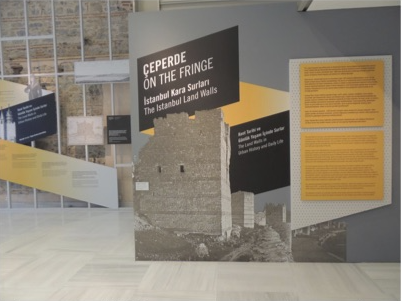

Picture 2. Exhibition entrance at ANAMED. Photo: İpek Yeğinsü

The welcoming panel at the entrance of the exhibition (Picture 2) elaborates on the same graphic elements observed in the poster. The black and yellow structure on which the texts are positioned replicate the structure of the land walls as a marker of boundaries and enclosure. The texts on the yellow stripe, on the other hand, are quotes taken from various authors ranging from Edmondo de Amicis to Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar that are not arranged in a chronological order; for instance, Schrader’s work from 1917 is followed by a de Amicis quote dated 1874. Moreover, the maps, images and texts organically placed around the yellow stripe add dynamism and open-endedness to the narrative, hinting at the overall design approach we will be experiencing inside the exhibition hall.

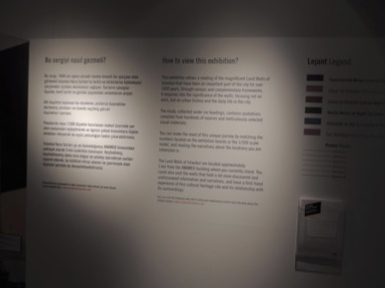

Picture 3. Exhibition entrance at ANAMED. Photo: İpek Yeğinsü.

The second panel (Picture 3) carrying the exhibition’s introductory text and the image from the poster is placed at the immediate vicinity of the exhibition hall. Here the following statement stands out as an effective summary of the exhibition’s main purposes: “The exhibition examines the existence of a structure of defense ˗ which has actually not seen a scene of battle since 1453 ˗ in urban life, not through verifying the truth of the written and visual resources but rather aiming to show the plurality of the memories, perspectives and representations”.

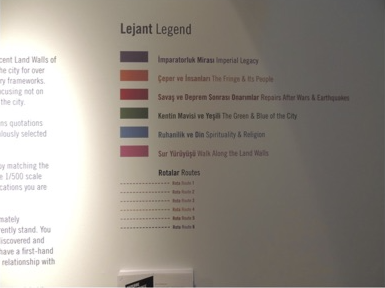

Pictures 4 and 5. Panel of instructions on “how to view this exhibition”. Photos: İpek Yeğinsü.

The exhibition hall is preceded by one more preparatory space: a smaller passage hall with an introductory panel where the exhibition team, the contributors and sponsors are listed and credited. But more importantly, on this wall the visitor finds a set of instructions on “how to view this exhibition” (Picture 4- 5). Here the principles of the exhibition design realized by Yeşim Demir Pröhl / Demir Tasarım are explained in detail; the text refers to the 1/500 scale model of the land walls installed at the center of the exhibition hall where each monument is assigned a number. Six color codes represent six thematic chapters, namely: “Imperial Legacy”, “The Fringe & Its People”, “Repairs After Wars & Earthquakes”, “The Green & Blue of the City”, “Spirituality & Religion”, and “Walk Along the Land Walls”. The visitor may choose to focus on one thematic chapter and then trace the monument route assigned to that color/chapter, or, vice versa, he can choose a monument and read the texts assigned to that number/monument in each thematic chapter (Picture 5). As stated in the instruction, the layout was chosen to “allow a reading […] through various and complementary frameworks”.

B.2. Inside the Exhibition Hall: Layers of Information and Plural Narratives

Mieke Bal (2012) sees the curatorial as an “act of framing”, and framing, in turn, “produces an event” (p. 180) and “points to a process” (p. 181). Blackman (2016) describes curation as “a performative practice that has the potential to perform, move, animate and re-move those narratives and experiences that are often disqualified, disavowed, submerged, displaced and discredited within particular scenes of entanglement” (p. 36). The exhibition “ON THE FRINGE” is an ideal example of such a curatorial approach, and this is rendered possible by two exhibition design elements: layers of information and the resulting plural narratives. Macalik sites Greenberg (2005) in arguing that content layering has an important role in creating a visitor experience both rich in information and emotion (2010, p. 94). According to Macalik (2010), “Modern exhibits have veered away from the linear narratives, avoiding a single storyline, which must be adhered to; instead multi-thread stories are assembled within distinct information pockets, as chapters in a spatial book. Layered information in a visceral montage of imagery and texts guide visitors to their next information interaction. The exhibitions, avoid singular narratives but instead distinct information areas, likened to scrapbooking (Macalik 2008)” (as cited in Macalik, 2010, p. 84).

Information layering is particularly important if various visitors with different levels of knowledge are simultaneously targeted. For Hughes (2015), “every large exhibition addresses a wide range of visitors, some with more knowledge of its theme than others. To accommodate their varied needs, designers and exhibitors create layers of information. Any exhibition can be layered in a great variety of ways. For example, there could be a layer for lengths of visit—short, medium or long—or for different interest groups” (p. 40). Thanks to the ways in which various chapters are presented and rendered readable independently of each other, as well as the plurality of media chosen for the presentation of the content, this exhibition allows for multiple versions of visiting as well, both in length (time) and depth (engagement). In Blackman’s words, (2016), the different media in this exhibition “compete, coexist and have complex genealogies of existence” (p. 41).

The use of plural media can also be effective in simultaneously engaging visitors with different types of learning orientations. Hughes (2015) identifies three types of learning in visitors: the visual learner is less interested in textual information and more involved with visually interesting presentations, while the auditory learner is most efficient when the content is communicated to him verbally, and the kinaesthetic learner prefers touching objects and interacting with the content (p. 42-43). On the other hand, departing from Bakhtin’s Carnival Theory (1984), Jun & Lee (2014) identify four ways in which a visitor dialogically engages with an exhibition: critical reflection as dialogue with the exhibition’s principle, creative expression as dialogue with the self, exploring interrelationship as dialogue with the context and free and familiar interaction as dialogue with other people (p. 249). Thus the combination of a variety of media in the exhibition design also has the potential to minimize the risk of losing the concentration of visitors with differing cognitive orientations.

Six main types of media used in this exhibition are:

-The Model: 13-meters long, the model is a 1/500 scale replica of the land walls and the surrounding topography, with markings of all the important monuments in the area (Picture 6). As the exhibition’s centerpiece, it is effective in encouraging the visitor to explore further and adding a third spatial dimension to the two-dimensional textual information and imagery exhibited on the walls. Each column erected as a monument marker has a number that sends the visitor to the corresponding information sections on the walls, and color codes indicate under which chapters each monument is being discussed.

Picture 6. The model surrounded by panels and displays. The map on the floor is distinguishable. Photo: İpek Yeğinsü.

Interestingly, the model is not left suspended in a void; it solidly sits within a much larger map drawn on the floor, a map of Istanbul including the Marmara Sea, and the visitor is both able and compelled to walk on it (Picture 8). At this point, it is crucial to touch upon the issue of architectural approach to textual information. According to Kim & Lee (2016), “nowadays, as the exhibition text plays a major role in information-based exhibitions, the scope of the typography, which used to be confined to the panel or board, has expanded to include all of the architectural surfaces—walls, ceilings and floors—of the exhibition hall” (p. 16). These scholars analyzed the effect of typography on communication in information-based exhibitions with a focus on “the use of the architectural surface as the expanded presentation interface”, including floors, walls and ceiling (p. 15). They discovered that the use of the architectural surface generated increased visitor attention and encouraged the latter to use more diverse routes, as well as providing better post-experience rates of remembering the presented information (p. 27), for the visitors were able to associate the content with a tridimensional spatial experience (p. 28). They add that attention and engagement as well as effectiveness of communication were even more significantly enhanced for the casual visitor who had no particular interest in the exhibition’s subject matter (Ibid.).

Picture 8. Detail from the map on the floor. Photo: İpek Yeğinsü.

-Texts: Except for the map on the floor and textual markings on the model and labels, the majority of the textual content is arranged into panels (Picture 9-10-11). The chapters are organized in subsections, an introductory text followed by panels each of which is dedicated to one monument referred to in the chapter. Quotes from specific authors add nostalgia and emotional framework to the otherwise informative descriptions. The chapters are supported by other media installed in and around the chapter, including videos, photographs, images and objects. Panels are not identically arranged, which adds dynamism to the layout.

Picture 9 and 10. General view from one of the chapters. Photo: İpek Yeğinsü

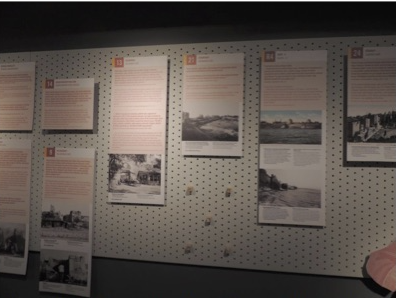

Picture 11. Closer view from the panels in a chapter. Photo: İpek Yeğinsü.

-Photographs: Photographs are used in two different ways. The majority of them are placed underneath the panel texts for illustrating their content. On the other hand, a group of photographic images are printed large and highlighted in a way that creates visual attraction points which reclaim the visitor’s concentration. These photographs also add a more organic feeling to the highly structured layout and have more emotional connotations such as sympathy and nostalgia (Picture 12).

Picture 12. Examples of photographs exhibited outside the panel structure. Photo: İpek Yeğinsü.

-Videos: Similarly, the videos are used either as panel inserts in chapters or in other independent arrangements (Picture 13). However, unlike the nostalgic photographs that function as a gateway to the past, the videos represent the visitors’ strongest access point to our present day. Some emerge as the documentary accounts of specialists and activists who have been developing projects around the current state of the walls. Other videos are presented as artistic experimentations. In other words, the videos constitute the exhibition’s contemporary element involving sociopolitical activism and hinting at an artist-as researcher approach, highlighting the current issues of ecology and cultural heritage preservation.

Picture 13. Examples of videos exhibited outside the panel structure. Photo: İpek Yeğinsü.

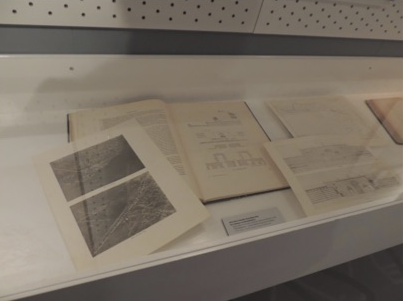

-Documents: Documents in the exhibition mainly consist of books and maps (Picture 14). They reinforce the exhibition’s didactic and archival character, and add dynamism to the layout.

Picture 14. Examples of documents from the exhibition. Photo: İpek Yeğinsü.

-Objects: According to Macdonald (2007), “by comparison with text, objects might be seen as relatively open to alternative interpretation” (p. 155). The objects are installed in the exhibition in an asymmetric and dispersed manner, either supporting the arguments presented in the chapters or facilitating the visitor’s introduction into the subject, also through more emotional connotations like those found in the photographs (Picture 15).

Picture 15. Example of object from the exhibition. Photo: İpek Yeğinsü.

C. EXHIBITION DESIGN AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE VISITOR: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY

C.1. Interview with the Curator

To test my in-situ observations, I interviewed the exhibition curator, Assoc. Prof. Figen Kıvılcım Çorakbaş, on how she approached this exhibition (Annex 1). In describing her curatorial intentions, she says: “My main concern was to employ different media to enable each visitor to create her/his own path through the multiple layers that the tangible and intangible qualities of the cultural heritage provide”. Her approach is in line with the scholarly accounts I presented in the preceding sections: the curator believes that a combination of different media and multiple layers of information allow enhanced visitor engagement through the construction of personalized narrative paths. She also adds that “[her] selection of the presentation methods followed [her] research on establishing relations between the tangible and intangible qualities of cultural heritage and developing appropriate interpretation and presentation methods”. In other words, she decided on the specific exhibition method only after the final content emerged, i.e. she did not force her content into a predetermined structure. The curator’s close collaboration with the designers throughout the process appears to have been another fruitful aspect of her approach: “The exhibition designers attended most of the meetings for the last six months during the preparation of the project. So they followed the development of the conceptual framework. Therefore, when all the textual and visual materials were submitted to them (and this was only one month before), they could respond very fast to the design needs of the exhibition”.

When I asked her if there were any elements such as lighting and color that she strategically used to generate affect in the audience, the curator said, “Yes, we discussed that lighting and color should help the visitor navigate easily through the themes and the massive amount of information presented within the scope of the exhibition”. Thus she defined the form of the visitor’s bond to the exhibition as one that was expected to emerge from an effective navigation in the vast pool of information. In other words, the exhibition design was conceptualized and expected to function as an ‘enabler’ of an intense visitor interaction with the content. Finally, when asked what she would have done differently if she could, Çorakbaş replied: “I may utilize more interactive digital methods to enhance the connection of the spatial and written data, if we have another chance to re-exhibit this material. Moreover, I would like to document better the visitors’ opinions about the World Heritage Site and about the exhibition”. Her remarks on interaction are particularly worthy of attention since they illustrate how much emphasis this notion has had in her overall approach. Regarding the documentation of the visitor response, on the other hand, the following survey conducted for the purposes of this paper provides a useful insight.

C.2. Visitor Survey

The survey (Annex 2) was placed at the entrance/exit of the exhibition hall and was made available to the visitors for an entire month, and the visitors participated to it on a self-service and voluntary basis. The questions aimed at understanding the relationship between six different media used in the exhibition design and three different forms of visitor engagement: information, emotion and curiosity. The survey also included questions targeting demographic data, to examine the relationship between visitor experience and variables such as age, sex and education level. The study produced eighteen eligible survey submissions. The collected data are presented in the table Annex 3.

The findings are summarized as follows:

1) 11 of the 18 participants are women and 7 are men;

2) 8 participants had graduate school education, 8 had university education, and 1 is a high school student. One participant did not specify his or her level of education;

3) Except for one participant who declared his country of origin as the USA, all the participants are of Turkish origin and reside in Turkey;

4) The age range is 16-75. 8 participants are below 30; 6 are in their 30s and 3 are 50+. Very interestingly, none of the participants are in their 40s and one participant did not specify his or her age;

5) The exhibition’s comprehensibility ratings ranged from 6 to 10 out of 10, with a highly successful average of 8.3;

6) A significant majority of the participants found the exhibition to be more informative than emotional or evoking curiosity, and the exhibition performed very poorly in terms of generating emotional response. However, when the visitors were asked to rate each of the 3 aspects separately from 1 to 10, ‘evoking curiosity’ produced a higher average (8.7) than ‘informative’ (8.4); also here the emotional aspect performed relatively poorly (6.9). This may indicate that the visitors’ initial expectation in visiting the exhibition was to acquire information but the exhibition layout also succeeded in evoking significant curiosity in them. The only score in favor of emotional effect came from the visitor with the only different country of origin, and, as predicted in the observational data, he placed a very high emphasis on photographs as the dominant medium of engagement;

7) An overwhelming majority of the participants marked the texts and the model as the most interesting elements in the exhibition. In other words, as the curator intended, the text- model structure appears to have had a crucial role in visitor engagement. When they were asked which medium performed best in generating information, emotion and curiosity, the text again had an overwhelming victory as the informative element. Photography, on the other hand, was by far marked as the most emotional medium, with no single marking as informative; the same informative score of zero also emerged for objects that performed relatively better in the emotional department, as I already observed in my in-situ analysis. Text, on the other hand, received zero emotional score; this is also interesting, considering the various authors’ quotes that were featured in the panels which, I thought, could have provided some emotional points of access through feelings of nostalgia. Finally, in terms of evoking curiosity, the model performed significantly better than all the other media;

8) Unsurprisingly, the highest scores for video came from participants in their early 20s; this age group also had a high level of engagement with the objects and the model, i.e. non- textual information;

9) In terms of education level, participants with a university degree had more response in favor of the informative aspect, whereas participants from graduate school had a more even distribution of scores between the information and curiosity aspects; this finding might have become less significant if the survey sample were larger;

10) The average score for the overall visitor experience emerged as 8.3 out of 10, indicating a significantly high rate of success. No significant difference exists between the scores given by the university level and graduate school participants. The average score for men is 8.6 and 8.8 for women, again indicating no significant difference.

D. CONCLUSIONS

The exhibition “ON THE FRINGE: The Istanbul Land Walls” is an ideal example of how presentation of multilayered information on plural media allows the visitors to engage with an exhibition’s content and draw satisfaction from the experience regardless of their demographic traits. The study relied on in-situ observation, the curator’s interview remarks and the visitor survey testing six different media used in the exhibition against three forms of visitor engagement based on information, emotion and curiosity. The survey findings indicate that visitor response is mainly in line with the curator’s original intentions, the most important of which is to allow for multiple readings and personalized narratives. The scaled model of the land walls rendered the textual information more accessible and in-situ navigation more engaging, and allowed the visitors to determine their own visit’s pace, route and depth. As the findings illustrate, the layout also evoked curiosity in the majority of the visitors who were hoping for an informative experience, i.e. another positive feedback if we remember the curator’s intention to encourage a visit to the actual physical site of the land walls.

The exhibition’s weakest aspect was its ability to evoke emotional response despite the use of nostalgic photographs, activists’ videos and quotes from seminal authors. The curator did not specify it as one of her main intentions but this element could have been exploited more thoroughly to evoke further curiosity and to encourage the visitors to take a more activist position regarding the preservation of the cultural heritage around the walls. It is also very interesting to note that younger visitors managed to establish a better connection with the videos; this might be both due to their less text and more image- oriented daily experience due to social media and digital technology, and the more contemporary issues addressed in the videos.

The survey definitely had its shortcomings. The sample could have been larger and offer more demographic variety, especially in terms of educational background; the questions could have been more detailed and descriptive. Nevertheless, the sample was sufficient to indicate certain tendencies and patterns, and the overall visitor satisfaction was evident and sufficient to illustrate that the majority of the curatorial targets were met thanks to the intelligent use of several elements of exhibition design. A similar study was conducted by Skydsgaard, Andersen and King (2016) examining the exhibition Dear, Difficult Body taking place at the Steno Museum in Aarhus, Denmark and targeting youngsters, more specifically, adolescents (p. 48-49). The museum (2008) announced the four design principles they employed in the exhibition as curiosity, challenge, narratives and participation, and the researchers attempted at measuring if these principles produced the effects they aimed to generate (Ibid.). They discovered that these principles in fact made a difference, but their cleverly combined use specific to each subsection in the exhibition was what made the difference significant and in the desired direction (p. 62-63). They add: “Our analysis has demonstrated that the systematic use of design principles has largely enabled a clear match between the aim of the exhibition and visitor outcomes” and “these findings suggest that the use of design principles is effective in informing exhibition design” (p. 65). The exhibition “ON THE FRINGE” is no exception.

“Bu sergi, Anadolu Üniversitesi Bilimsel Araştırma Projeleri Komisyonu tarafından kabul edilen 1604E179 nolu proje kapsamında desteklenmiştir. Sergide, TÜBİTAK tarafından desteklenen 115K225 nolu proje kapsamında yapılan çalışmalardan faydalanılmıştır. This study was supported by Anadolu University Scientific Research Projects Commission under the grant No: 1604E179. The content of the exhibition is derived from the research carried out for the TUBITAK Project No:115K225.”

You can reach the complete study at ANAMED’s website.