I moved from Seattle to Istanbul in June 2017 for my most current archival venture in pursuit of the story of marginal Jews of nineteenth-century Izmir.

While applying for ANAMED’s doctoral fellowship, on my project description I wrote: “This research aims to give voice to marginal members of the community who have long remained on the margins of a minority as well as the margins of Jewish historiography.” The act of giving voice started with a twenty-minute bus trip from Taksim to Ottoman State Archives of the Prime Minister’s Office in Kağıthane on a cold September morning. I had Arlette Farge’s book The Allure of the Archives in one hand and a double Turkish coffee on the other.

Some of us have favorites in the academia. Mine is a French social historian of eighteenth-century Paris, Arlette Farge. The Allure of the Archives has been my guide for the last five months. While reading and re-reading her experience in the Archives of the Bastille, I felt like her sitting next to me in the reading room of the Ottoman State Archives, laughing at my nervous breakdowns and appreciating six-hour straight stares at the computer screen followed by migraine attacks during the night. Her understanding of the lived experiences and emotive states of her subjects assisted me while forming the theoretical and methodological foundations of my dissertation project. I wanted to write like her, but more importantly, I wanted to tell stories of ordinary people as Farge did brilliantly. I have always loved stories, and she told good ones with thieves, working people, and children nurtured with rumor, quarrels, and various other forms of drama. In her works, common figures from eighteenth-century Paris come to life once they step off the dusty manuscripts, appearing as human beings with dreams and disappointments, and above all, with genuine emotions.

My dissertation project at the University of Washington focuses on the historical conditions which drove and sustained intracommunal exclusion of marginal Jewish figures in Ottoman urban settings, specifically addressing this question during the period 1847–1913 in the Jewish community of Izmir. By studying the relationship between marginality, exclusion, and Ottoman modernity I try to expand the cast of characters of Ottoman Jewish history while distancing my work from the existing literature which focuses mostly on male elite Jews. Although a great number of documents related to Izmir disappeared due to fires, dampness, and wars, luckily Ottoman archives still hold stories of İzmirli [from Izmir] beggars, orphans, prostitutes, criminals, diseased, converts, poor, quarrelers, and vagrants, situated in their daily mayhem.

Archival documents related to my research are mostly traces of official correspondence regarding the protection of the public order as marginals’ pre-assumed violence, immorality, and lawlessness were seen as essential elements of their deviance. Marginals had to be policed and punished for the greater public good. Related archival documents are brief and often I consider myself lucky if I get to learn the name and age of the “marginal.” Just like personal details, lived realities also disappear among the honorary salutations to Sultan and state officials. Hence, often my imagination comes to my rescue, helping me to fill the void around these individuals by asking never-ending questions. What would an Ottoman subject Jewish woman do when she “loses her mind (şuur kaybı)” while abroad, with no money or family? Why would two young Jewish men stock animal bones, nails, and horns in a store? Why did three İzmirli men kill and dismember their friend while gambling? What was the behavior that led a Jewish man to be labeled as insane at an official ceremony attended by Sultan?

I keep searching, transcribing, and translating. I feel overwhelmed by the amount of the material. Farge in her book sadly confesses that a whole lifetime would not be enough to read the entirety of the eighteenth-century French judicial archives. I will not be able to read the entirety of Ottoman archives, nor the communal archives located in Jerusalem. Through the immensity of the collections, I realize once again my mortality, in a harrowing way. Actually, soon I was to realize that it was not only the constant reminder of my mortality but something else would be my problem in the Ottoman archives.

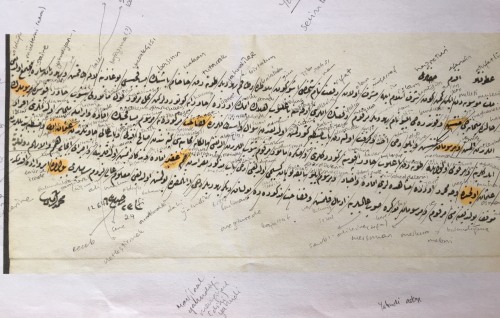

I spend most of the weekdays sitting in the reading room, staring at a computer screen, going through documents and questioning what can be gleaned from them about life and death of these marginals. I click on documents with the hope of finding something relevant, something interesting. I struggle as I try to read hand-written documents from the 1840s. In previous years, the realm of printed material of Ottoman Turkish journals and newspapers was a safe haven for me. Printed letters with their rigidity and uniformity rarely left me confused. Whereas, the uncanny curves, mysterious dots up and above the letters make me nervous as I go over the hand-written material. Nevertheless, within time I got familiar with the hand writing styles and even started memorizing the names of İzmirli marginals. If being part of marginal networks of a nineteenth-century port city was similar to being a member of a social club, I was the nosey newcomer.

With the arrival of winter, İzmirli marginals were already constant figures dwelling in my brain. While re-reading their documents, trying to find more in the archives about their story, I started to refer to them by their first names and without the requirement of being kind or politically correct, I started giving them names: Hayim the thief, Mazalto the mad, Yako the arsonist… They were labeled as thieves, prostitutes, murderers, and mads during their life time. I once again initiated the cycle of name-calling without knowing whether they were rightfully labeled and judged. I accept the fact that, probably, I will not learn more about these people due to the limits of the archive, about the “prostitutes” residing in Izmir during the 1870s. I will never understand the extent of their experience of being forced to change houses within the city because of their neighbors’ complaints. I will never grasp the experience of their forced exile to Konya. Nevertheless, almost 150 years later, I am part of the process as a researcher, bystander, name-caller, and also as an İzmirli. Throughout this process, I consider these individuals’ agency and experience and often amazed by their use and manipulation of various survival tactics. Yet, the treatment they received from their community and state urges me to reconsider the concept of justice. Now, having read more than hundred cases regarding the marginal figures of the city, I feel overwhelmed by all the misfortunes, hardships, and miseries. In other words, the burden of the archive hit me hard right after its allure. Perhaps, I was not ready for the traps and snares of the archives.

Three months ago, an archival document of a Jewish woman made me realize the human suffering I have been dealing with at the Ottoman archives. Mazalto, labeled insane, had nowhere to go once the rabbinate declared that they are no longer willing to take care of her due to her “violent” behavior. The overcrowding crisis of mental asylums of the Empire during the late nineteenth century worsened the situation as none of the state institutions were able to offer her a place. The official correspondence regarding her situation between the authorities lasted for five years. Mazalto’s fate is still unknown. Stories continue piling up on my desk. Patients of the mental asylum in Edirne chained to the walls, a Christian missionary attempting to rape Armenian orphan girls, a neighbor beating a young Jewish boy to death.

As I was going after a truthful narrative, I was not expecting to be struck by the emotional burden of the archival stories. When I first started thinking about marginal figures of the Jewish community of the nineteenth-century Izmir three years ago, I was trying to find my way in the grad school. I never fully considered the bare existence of human suffering. My academic curiosity in deviance and marginality brought me to these stories, and now I realize that it is very difficult to analyze these historical events in their historical context to create a meaningful narrative. Farge in her book states that the historian must be both close to and distant from the figures, words, and events emerging from the archives since she has to intervene and interpret. Recently, I started thinking that figures I found at the archives are more than their strangeness as they reflect the popular conceptualizations of deviance and social order are powerful indications of state authority and social norms. Today, as I still try to find ways to narrate the emotive aspect of my research, I realize that going after “the strange” in the archives might be another trap especially in a state archive where the line between truth and lies is blurred. But, how to tell if the archive is lying?

“A historical narrative is a construction, not a truthful discourse that can be verified on all of its points,” says Farge. (p. 95) Archival documents from the Ottoman archives usually do not describe people in full. It cuts them out of their families, friends, and communities while displaying only one side of their identities. The discourse of the state is visible in the texts with its authority, arrogance, and denial. Farge is correct, from the very start, the archive plays with the truth as with reality and the researcher’s job becomes a challenging one. Her advice to look deeper, beyond the immediate meaning, and interpret the circumstances that permitted and produced them requires experience and practice.

Just like its allure, archive’s burden is inescapable in many ways, and often the line dividing the attraction and affliction becomes invisible. Nor the archive neither the performance of research is limited by the walls of the repository with CDs you can purchase loaded with thousands of PDFs of the archival documents. I carry the bits and pieces of this gigantic repository to fancy third wave coffee shops of Istanbul and dentist appointments. Maybe most importantly, every month for a couple of days they travel with me to Izmir, to my hometown and also the hometown of whose misfortunes I have been reading.

Now I have in my hands stories of marginality and human suffering. As these stories sadden me, at the same time, they strengthen my commitment to telling the stories of marginal but ordinary, invisible but noticeable individuals. Trying to avoid romanticism of a young researcher, I refrain from the phrase of “feeling the past.” I constantly want to learn more about “my marginals,” and most days I end up thinking if the dead could speak how better my life would be. In this research, silence is what I am struggling with.

The desire to understand is a tough one, and my experience at the Ottoman archives have been a challenging one. When I question my shock in the face of misery reflected in the archival documents, I blame my naiveté probably stemming from my childhood spent at the Aegean countryside surrounded by seventeenth-century pastoral poetry-like figures. Today, I perceive the archives as a microcosm of past lived experiences, a dark place born out of a moderately coordinated chaos. Yet, the question still lingers: Is it ever possible to find happy instances in an imperial archive?