Dr.Taranto, seramik malzeme üzerinde teknolojik ve işlevsel iz analizi konusunda uzmanlaşmış bir arkeologdur. Esas olarak, eski toplulukları daha iyi anlamak için yeme davranışını kültürel bir yön olarak araştırmakla ilgilenmektedir. Bu amaca ulaşmak için, Roma Sapienza Üniversitesi’ndeki LTFAPA laboratuvarında öğrendiği gibi etnografi, deneysel arkeoloji ve kullanım-değişim analizi gibi farklı yaklaşımları entegre olarak kullanmaktadır. 2022 yılında Autonomous University of Barcelona ve Roma Sapienza Üniversitesi ile ortak araştırma yaparak Tarih Öncesi Arkeoloji alanında doktora derecesi almıştır. Doktora araştırması boyunca, İstanbul Üniversitesi ve Koç Üniversitesi gibi çeşitli laboratuvarlarda çanak çömlek örneklerini analiz ederek Geç-Neolitik dönem ‘Husking Tray’ olarak lüteratüre geçmiş kabuk soyma kaplarının üretim aşamalarını ve işlevini incelemektedir. ANAMED doktora sonrası araştırmacısı olarak, Güneydoğu Anadolu ve Yukarı Mezopotamya’da Geç Kalkolitik dönemin en belirgin çanak çömlek formlarından biri olan Coba kaselerin işlevi üzerine bir araştırma yürütmektedir. Araştırma, Değirmentepe ve Arslantepe’deki arkeolojik alanlardan elde edilen bu çanak çömlek formuna ait parçaların kullanım-aşınma analizini ve coba-kase replikalarının deneysel olarak yeniden üretilmesini ve kullanılmasını içermektedir.

The Functions of Late Chalcolithic Conical Bowls from Eastern Anatolia Investigated by Way of Experimental Activity and Trace Analysis

Sergio Taranto

During the fifth–fourth millennia BCE, profound sociocultural changes seem to have involved communities in Greater Mesopotamia and southeastern Anatolia. Indeed, archaeological evidence suggests a gradual shift in the social organization of communities toward more stratified forms.[1] According to many scholars, the conical bowls found concentrated in large quantities are one of the elements of material culture that best testify to these transformations. The conical bowls were fashioned into a variety of vascular forms. This heterogeneous group of bowls is currently the subject of various classifications according to different interpretations by scholars; some of them are referred to as coba bowls—this term is related to the site, Coba Höyük (Sakçegözü), where fragments belonging to this ceramic form were first found. These ceramic forms were produced by potters who shaped coarse-tempered clay with organic inclusions. The bowls were medium in size and had relatively thick walls. Usually, the outer surface of these vessels was scraped.[2]

Because of the relatively standardized production and the fact that they have often been found in large concentrations, these bowls have been interpreted by most scholars as mass-produced vessels used in connection with the distribution of rations.[3] In fact, these features would indicate their use as ceramic support for the distribution/processing of food for a large number of individuals, implying the existence of a kind of incipient “contractual relationship.”

In this sense, these vessels constitute material evidence of socio-economic changes in the structural organization of ancient Near Eastern communities. From this perspective, the bowls would be interpretable as evidence of a change in interpersonal relations, prefiguring the epochal changes in social relations that would materialize in the late fourth millennium BCE with the emergence of the state in Lower Mesopotamia.

Although much debated, several studies have been conducted and various hypotheses have been put forward in relation to the function of the later bevelled rim bowls; in this case, scholars have proposed that these containers might have been used for serving beer, porridge, and cereals,[4] as molds for baking bread,[5] or for various other purposes.[6] Moreover, pictures also exist for another set of conical bowls from Old Kingdom Egypt, the bedja, suggesting that they were used to bake bread.[7] In this sense, it is interesting to note that, in an earlier period (6400–5900 BCE), the tradition of baking bread in ceramic containers, so-called husking trays, was most likely already widespread in the Near East, as several studies reveal.[8]

In contrast, the actual function of Late Chalcolithic mass-produced bowls has been little investigated: scholars have proposed hypotheses that have so far remained unverified by further analysis. Mass-produced bowls could have been used for individual consumption of liquid or semi-liquid foods, in one of the ways hypothesized for later ceramic forms (for baking bread or serving beer, “porridge,” or grain-based foods), or even for kneading flour and dough. Although the actual functions of the conical-shaped bowls must necessarily be studied in relation to the specific contexts in which each was recovered, this research constitutes the first focused study on the function of mass-produced bowls from the Late Chalcolithic period.

The research integrates an experimental approach with use-alteration analysis.

The experimentally obtained data can help provide a preliminary indication of the possible functions of the bowls. The experimental activity was conducted in Sicily in the fall of 2022 and the spring of 2023 with the aim of verifying the suitability of the ceramic form under analysis with respect to some hypothesized activities. In fact, the experimental trials make it possible to discard less appropriate functional hypotheses and verify the degree of appropriateness of others. In particular, it relates the morphological and compositional characteristics of the vessel to its possible functions. In practical terms, conical bowl replicas were shaped, finished, and fired (Fig. 1). Subsequently, they were used for cooking (Fig. 2). In particular, the bowls were used for the preparation of grain-based foods with different cooking techniques in both a domed oven and a fireplace.

The experimental evidence, in addition to providing an overview of the actual possible functions of the ceramic forms with respect to specific activities, allows for the creation of a use-wear reference collection necessary for use-alteration analysis.

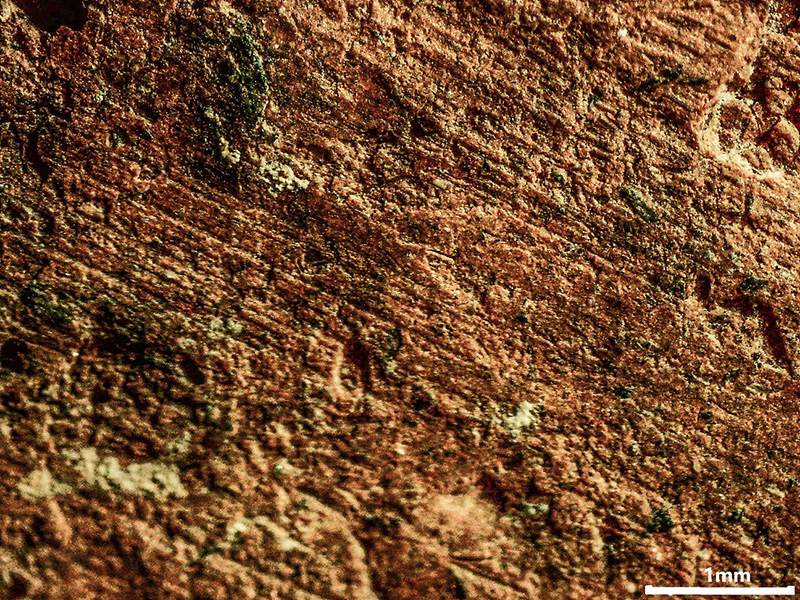

This type of analysis is based on the presence or absence of coherent similarities between the traces developed on the surfaces of experimental replicas during their use and those present on archaeological finds. The analysis is carried out through macroscopic and microscopic observation of ceramic surfaces of the artifacts. The study of the technological traces created on the surface of conical bowls during their construction is allowing us to define specific evidence of the techniques and gestures adopted by potters in shaping and finishing mass-produced bowls (Fig. 3). Similarly, the study of the use-wear developed during their use allows us to narrow the field of the possible functions of the archaeological artifacts.[9] This analysis activity was carried out through microscopic observation of experimental and archaeological artifacts at ANAMED, the ARHA laboratory of Koç University, the BIAA in Ankara, the prehistory laboratory of Istanbul University, and the Rıdvan Çelikel Archaeological Museum. The samples analyzed in this study came from several sites, including Sakçegözü, Değirmentepe, and Hassek Höyük.

In conclusion, the research on the function of mass bowls undertaken at ANAMED has produced significant, albeit preliminary, information on the function of these artifacts, whose use has been of exceptional importance in human history.

References

Baldi, J. S. “Coba Bowls, Mass-Production and Social Change in Post-Ubaid Times.” In After the Ubaid. Interpreting Change from the Caucasus to Mesopotamia at the Dawn of Urban Civilization (4500–3500 BC). Papers from The Post-Ubaid Horizon in the Fertile Crescent and Beyond. International Workshop held at Fosseuse, 29th June–1st July 2009, edited by Catherine Marro, 393–416. Istanbul: Publications de l’Institut Français d’Études Anatoliennes-Georges Dumézil, 2012.

Balossi, F. “The Beginning of the Late Chalcolithic Occupation at Arslantepe, Malatya.” In After the Ubaid. Interpreting Change from the Caucasus to Mesopotamia at the Dawn of Urban Civilization (4500–3500 BC). Papers from The Post-Ubaid Horizon in the Fertile Crescent and Beyond. International Workshop held at Fosseuse, 29th June–1st July 2009, edited by , 235–59. Varia Anatolica 27. Istanbul: Publications de l’Institut Français d’Études Anatoliennes-Georges Dumézil, 2012.

Chazan, M., and M. Lehner. “An Ancient Analogy: Pot Baked Bread in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia.” Paléorient 16, no. 2 (1990): 21–35.

Frangipane, M. La nascita dello Stato nel Vicino Oriente. Rome-Bari: Laterza, 1996.

Goulder, J. “Administrators’ Bread: an Experiment-Based Re-Assessment of the Functional and Cultural Role of the Uruk Bevel-Rim Bowl.” Antiquity 84 (2010): 351–62.

Jacquet-Gordon, H. “A Tentative Typology of Egyptian Bread Moulds.” In Studien zur Altägyptischen Keramik, edited by Do. Arnold, 11–24. SDAIK 9. Mainz am Rhein, 1981.

Perruchini, E., C. Glatz, S. Gravdal Heimvik, R. Bendrey, M. M. Hald, F. Del Bravo, S. M. Sameen, and J. Toney. “Revealing Invisible Stews: New Results of Organic Residue Analyses of Beveled Rim Bowls from the Late Chalcolithic Site of Shakhi Kora, Kurdistan Region of Iraq.” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 48 (2023): 103730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2022.103730.

Pollock, S. “Feasts, Funerals, and Fast Food in Early Mesopotamian States.” In The Archaeology and Politics of Food and Feasting in Early States and Empires, edited by T. Bray, 17–38. New York: Kluwer Academic Press, 2003.

Potts, D. T. “Bevel-Rim Bowls and Bakeries: Evidence and Explanations from Iran and the Indo-Iranian Borderlands.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 61 (2009): 1–23.

Sanjurjo-Sanchez, J., J. Kaal, and J. L. M. Fenollos. “Organic Matter from Beveled Rim Bowls of the Middle Euphrates: Results from Molecular Characterization using Pyrolysis-GC-MS.” Microchemical Journal 141 (2018): 1–6.

Skibo, J. M. Pottery Function. A Use-alteration Perspective. New York: Springer, 1992.

Taranto, S. “Pot Baking: Revisiting an Ancient Analogy.” SocArXiv (2021), open access.

Taranto, S., M. Portillo, A. Gómez Bach, M. Molist, M. Le Mière, and C. Lemorini. “Investigating the Function of Late-Neolithic Husking Trays from the Syrian Jazira through Integrated Use-Alteration and Phytolith Analyses.” Journal of Archeological Science, Reports 47, no. 1 (2023): 103694.

[1] M. Frangipane, La nascita dello Stato nel Vicino Oriente (Rome-Bari: Laterza, 1996).

[2] F. Balossi, “The Beginning of the Late Chalcolithic Occupation at Arslantepe, Malatya,” in After the Ubaid. Interpreting Change from the Caucasus to Mesopotamia at the Dawn of Urban Civilization (4500–3500 BC). Papers from The Post-Ubaid Horizon in the Fertile Crescent and Beyond. International Workshop held at Fosseuse, 29th June–1st July 2009, ed. EDITORS?, Varia Anatolica 27 (Istanbul: Publications de l’Institut Français d’Études Anatoliennes-Georges Dumézil, 2012), 235–59.

[3] J. S. Baldi, “Coba Bowls, Mass-Production and Social Change in Post-Ubaid Times,” in After the Ubaid. Interpreting Change from the Caucasus to Mesopotamia at the Dawn of Urban Civilization (4500–3500 BC). Papers from The Post-Ubaid Horizon in the Fertile Crescent and Beyond. International Workshop held at Fosseuse, 29th June–1st July 2009, ed. EDITORS? (Istanbul: Publications de l’Institut Français d’Études Anatoliennes-Georges Dumézil, 2012), 393–416.

[4] S. Pollock, “Feasts, Funerals, and Fast Food in Early Mesopotamian States,” in The Archaeology and Politics of Food and Feasting in Early States and Empires, ed. T. Bray (New York: Kluwer Academic Press, 2003), 17–38.

[5] M. Chazan and M. Lehner, “An Ancient Analogy: Pot Baked Bread in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia,” Paléorient 16, no. 2 (1990): 21–35; D. T. Potts, “Bevel-Rim Bowls and Bakeries: Evidence and Explanations from Iran and the Indo-Iranian Borderlands,” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 61 (2009): 1–23; J. Goulder, “Administrators’ Bread: an Experiment-Based Re-Assessment of the Functional and Cultural Role of the Uruk Bevel-Rim Bowl,” Antiquity 84 (2010): 351–62; J. Sanjurjo-Sanchez, J. Kaal, and J. L. M. Fenollos, “Organic Matter from Beveled Rim Bowls of the Middle Euphrates: Results from Molecular Characterization using Pyrolysis-GC-MS,” Microchemical Journal 141 (2018): 1–6; S. Taranto, “Pot Baking: Revisiting an Ancient Analogy,” SocArXiv VOLUME? (2021): PAGES?.

[6] See E. Perruchini, C. Glatz, S. Gravdal Heimvik, R. Bendrey, M. M. Hald, F. Del Bravo, S. M. Sameen, and J. Toney, “Revealing Invisible Stews: New Results of Organic Residue Analyses of Beveled Rim Bowls from the Late Chalcolithic Site of Shakhi Kora, Kurdistan Region of Iraq,” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 48 (2023): 103730.

[7] H. Jacquet-Gordon, “A Tentative Typology of Egyptian Bread Moulds,” in Studien zur Altägyptischen Keramik, ed. Do. Arnold, SDAIK 9 (Mainz am Rhein : PUBLISHER?, 1981), 11–24.

[8] Chazan and Lehner, “Ancient Analogy;” S. Taranto, M. Portillo, A. Gómez Bach, M. Molist, M. Le Mière, and C. Lemorini, “Investigating the Function of Late-Neolithic Husking Trays from the Syrian Jazira through Integrated Use-Alteration and Phytolith Analyses,” Journal of Archeological Science, Reports 47, no. 1 (2023): 103694.

[9] J. M. Skibo, Pottery Function. A Use-alteration Perspective (New York: Springer, 1992).

If this is a direct quotation, provide citation. If not, remove quotation marks.