Dr. Salay, Antikçağ Akdeniz’inde yerel/bölgesel gemi inşa geleneklerinin devamlılığını gösteren arkeolojik kazı sonuçlarıyla deniz taşımacılığı ağlarını temsil eden verileri yan yana getiren bir araştırma projesi yürütüyor. Proje, değişen ulaşım ağlarının Antikçağ’da gemi mimarisinin gelişimini nasıl etkilemiş olabileceğini anlamayı amaçlamaktadır.

Research Title: The Technology of Ancient Maritime Trade: The Connection Between Mediterranean Maritime Networks and Ancient Naval Architecture

Dr. Salay is conducting a research project juxtaposing data representing maritime transportation networks along with results of archaeological excavations demonstrating the persistence of local/regional shipbuilding traditions in the ancient Mediterranean with the goal of understanding how changing networks may have affected the development of naval architecture in antiquity.

Fellow’s End of the Academic Year Research Report:

The Technology of Ancient Maritime Trade

For those outside the field, it is important to keep in mind that the discipline of maritime archaeology is comparatively still extraordinarily young. The excavation generally considered to be the first “modern” underwater archaeological excavation, in fact, is only slightly more than six decades old. By comparison, if we accept for the sake of convenience that Herodotus was the father of history, or that Vitruvius is the first exponent of architectural theory, we can see that maritime archaeology is still in its infancy. From a practical perspective, what that means is that the field is in a virtual constant state of flux. New tools are being introduced all the time, and new discoveries are perpetually changing our understanding of the dynamics of ancient humans’ interactions with aquatic environments.

The initial impetus for this project stems from a desire to leverage two recent emerging trends in the maritime archaeology of the ancient Mediterranean: first, the growing adoption and contributions of Geographic Information Systems (GIS); second, the results of ongoing fieldwork, particularly in the demonstration of persistent regional shipbuilding traditions (Fig. 1). In recent years, continuing excavations and the study of the results of those excavations have revealed distinct, regional shipbuilding traditions in addition to those already chronicled. Since the groundbreaking work of Pomey at the Place Jules-Verne at Marseille in the early 1990s,[1] the existence and nature of a distinct and presumably Greek tradition of boatbuilding using ligatures to fasten the architectural members has been well established (represented by red squares in Fig. 1). However, more recently, new discoveries have brought to light two distinct sewn-boat traditions in the Mediterranean, one in the north Adriatic and Danube River basin using ligatures to join the ship timbers (represented by yellow circles in Fig. 1), and another in the northwest Mediterranean using a system of “internal lashings” to fasten the frames to the hull (represented by blue circles in Fig. 1).[2]

Fig. 1. Locations of excavated remains of ancient sewn-boats in the Mediterranean (Greek, northwest Mediterranean, and north Adriatic traditions).

One of the principal motives for carrying out this project with ANAMED has been the ability to incorporate the work of the Koç University Mustafa V. Koç Maritime Archaeology Research Center (KUDAR) and the Ancient Maritime Dynamics Project (AMD) which uses GIS to model maritime connectivities in the ancient Mediterranean. The intent has been to create a geospatial database of the various sewn-boat traditions in the ancient Mediterranean and to incorporate the data from the AMD in order to produce a picture of the development of naval architecture relative to the development of increasingly robust maritime trading networks that reached levels of exchange in the Late Republic and Early Empire that would not be rivalled for another millennium and a half. The operating hypothesis has been that emerging maritime networks were instrumental in forming the patterns by which new technologies were adopted and/or traditional methods of shipbuilding were retained. As part of this process the aim was to address several related questions: 1) How did cultural factors affect the formation of maritime networks and patterns of technological change? 2) What was the impact of economic activity on technological change (or the lack thereof)? 3) How did the adoption of new technology influence economic growth and the expansion of ancient maritime trade?

Not surprisingly, there have been some bumps in the road along the way. First of all, working with a database that has been curated and collected by someone else always presents difficulties. Each individual inevitably organizes and labels data in idiosyncratic ways, influenced by their own personal preferences, as well as their specific research questions and aims. As a result, a certain amount of time was spent becoming familiar with the AMD data and the ways in which it was organized. At the same time, there was an additional learning curve related to the software used to process the data. For this project, I am using ArcGIS, which has become the standard GIS platform for the majority of archaeological applications. While I am familiar with the tools and capabilities of the software, I am nowhere near an expert, and that has often meant several days or more of frustration spent in figuring out how to perform functions of which I know ArcGIS to be capable but am simply not fluent enough to carry out with the same facility as someone more adept with the software would.

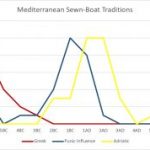

At the moment, the research has yielded some early results that I did not expect. Initially, I assumed that the progression of the different shipbuilding traditions would have followed more or less similar developmental patterns, even if those patterns may have taken place at different junctures. However, there are some notable differences that I am currently wrestling with and attempting to understand more fully. First of all, the Greek tradition exhibits a clear process of transformation, visible in the excavated ship remains, of a shift in the method of construction from the use of ligatures to pegged mortise-and-tenon joinery beginning in roughly the middle of the sixth century BCE and culminating by the end of the fourth century BCE (Fig. 2). However, the northwest Mediterranean tradition (which I regard as a Punic influence following the arguments of de Juan[4]) exhibits significant development and innovation from the earliest examples at the end of the seventh/beginning of the sixth century BCE to its peak in the Late Republic but shows no evidence of adaptation to a different technique prior to largely disappearing over the course of the first century CE. Meanwhile, the north Adriatic traditions, particularly the Istro-Liburnian technique, demonstrate remarkable stability over the entire length of their existence for the better part of two millennia, from the LBA/EIA and fading out but still surviving, albeit in reduced numbers, long after the fall of Rome.

Fig. 2. Time-series chart of recovered/excavated examples of boats securely identified with Mediterranean sewn-boat traditions.

It is here that the project currently rests. I am still in the processing stages of correlating the AMD data related to levels of maritime commerce and observable patterns of connectivity with the data regarding the different sewn-boat traditions and trying to make sense of it. There are some interesting initial observations to be made from this juxtaposition, although I am not yet to the point at which I feel confident making any definitive claims. Thanks to the KUDAR-ANAMED fellowship, the cooperation of KUDAR Director Dr. Matthew Harpster, and the supportive staff at ANAMED, I have the opportunity and resources to bring this project to its conclusion and expect to produce the results of the project for publication over the summer.

[1] P. Pomey, “Les épaves grecques du VIe siècle av. J.-C. de la place Jules-Verne à Marseille,” The Nautilus 14 (1998): 147–54.

[2] For an overview of these finds and the current state of scholarship, see P. Pomey and G. Boetto, “Ancient Mediterranean Sewn‐Boat Traditions,” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 48 (2019): 5–51.

[3] For an explanation of the method and approach of the AMD project, see M. Harpster and H. Chapman, “Using Polygons to Model Maritime Movement in Antiquity,” Journal of Archaeological Science 11 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2019.104997.

[4] C. De Juan, “Técnicas de arquitectura naval de la cultura fenicia,” Revista de Prehistoria y Arqueología de la Universidad de Sevilla 26 (2017): 59–85.