ANAMED Editor and Publications Coordinator Özge Ertem shares her journey with Yusuf Franko, from her first encounter with ‘L’expiation’ to her involvement in ANAMED’s recent exhibition ‘The Characters of Yusuf Franko: An Ottoman Bureaucrat’s Caricatures’…

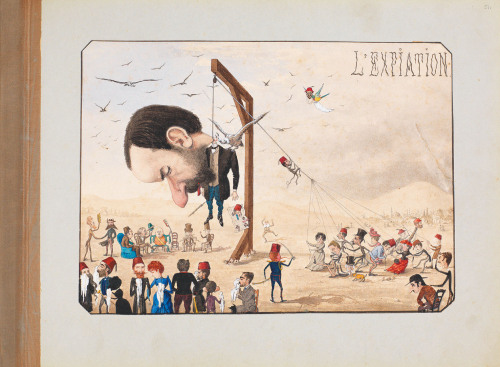

I met Yusuf Franko for the first time through “L’expiation,” the last drawing in his album of caricatures. It was almost a year after my farewell to ANAMED where I was previously working as Head Librarian (2013–2015). I had left Istanbul in order to continue post-graduate studies for a year, and came for a few days in spring 2016 to visit my friends and former colleagues. While I was in her room, Buket (Coşkuner), ANAMED Manager, showed me the color photocopy of a magnificent album. Something unique, full of elegantly and wittily drawn caricatures from the 19th century… Scanning the album, randomly I opened the last page and became amazed at what I saw: “L’expiation.” Yusuf’s last caricature where he drew himself as being hung by the characters seen all throughout his album. As K. Mehmet Kentel, my colleague and the writer/consultant in the exhibition project nicely put forward, it was “The Death of a Caricaturist” at the hands of the characters he drew. He was not just playing with the characters, the subject-material seen throughout the whole album; but he was playing with death: His own symbolic (maybe also physical) death. In vivid colors. If it was a Hollywood movie, soon after that moment he could meet Whoopi Goldberg in Purgatory, in white clothes, and watch his funeral together with her. Yusuf Franko, known to be an Ottoman bureaucrat, a governor-general — all serious and scary titles even for a student of Ottoman history —seemed also to be a man capable of looking into both his own “self” and life, and his social surroundings with a bird’s eye view. At least his caricatures gave that impression to me. I had just scanned the album then, and I had not yet any profound idea about what Lebanese people thought of him, or what was happening in Pera’s graveyards during the rich tea hours, balls, dances and high-society events he also attended. A few months later, here on Istiklal Avenue, in a surrounding where his daily routine took place, we started the book project that accompanied the exhibition on his caricatures. Thanks to the whole team, our journey with Yusuf Franko at ANAMED would soon teach me more about him and Pera, complicate his story, juxtapose the story of an individual (an artist/bureaucrat one) with the history of a city in transformation, and meanwhile personally help me gain experience in my new job at ANAMED.

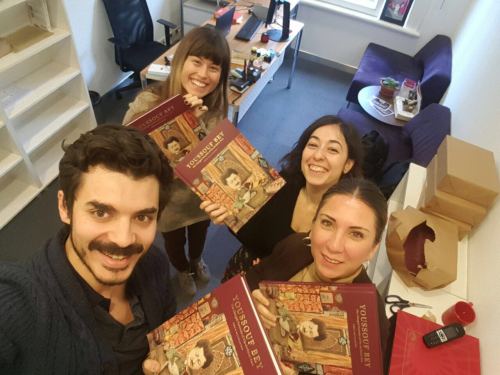

Yusuf Franko was my first task as ANAMED Editor and Publications Coordinator. I was in charge of preparing for publication and copy-editing two volumes of material, including a facsimile of Yusuf Franko’s album and an edited book of articles based on his caricatures. I was lucky because I had a chance to work closely and thus discuss in detail the issues at stake in different moments directly with the authors Bahattin Öztuncay (curator/editor), Sinan Kuneralp (consultant), K. Mehmet Kentel (consultant/also author of exhibition texts), Guillaume Doizy, Ebru Esra Satıcı (project coordinator), Umur Çelikyay (translator), Yeşim Pröhl (designer), Didem Uraler Çelik (design implementor), Buket Coşkuner, Şeyda Çetin (exhibition team), and Chris Roosevelt (ANAMED Director). My colleagues at KU Press, our neighbors in the building, also kindly answered my questions whenever I felt the need to consult their experience. This collaboration was one of the motivating parts of my first task.

One of the first challenges was how to find a solution for giving numbers to figures that corresponded to the order of caricatures in the original album. The original album had no page numbers; we needed to create our own logic for cross-referencing. The appendix prepared by Sinan Kuneralp was extremely helpful. We had now a draft key which we could use both for our and the reader’s orientation. These numbers in the appendix formed the plate numbers we gave to the caricatures cited in the articles. We were worried whether it would be too complicated to use both a figure and plate number for the same visual material; the organization was clear and obvious, however. Cross-referencing back and forth between the facsimile and the article book worked well. Another challenge was the vocabulary, to understand and analyze properly the linguistic “charge” behind the words ‘Types et Charges,’ Yusuf’s own title for his album. It took us some time, but finally, after fruitful discussions with colleagues and professors (Thank you Prof. E. Akarli and Yavuz Aykan!), we were feeling more confident about the way we translate and use these phenomena in their historicity. Being a researcher, I have been trained in particular academic styles of writing, and it is still always a challenge. Now, carrying its full responsibility on my shoulders, language was even more of a challenge. At the same time, I started to appreciate the etymological endeavor even more. Amidst an almost common feeling when “everything solid continued to melt into the air,” language and words themselves, phrases, the titles in captions and meanings hidden in the jokes of Yusuf Franko, even punctuation marks helped me hold onto the concrete more. Yes, dealing with them was sometimes extremely boring (Thank you also Chicago Manual 16th edition!), but thinking about language profoundly, and especially about a witty and talented human’s language, definitely enriched my perspective, both as a researcher historian and as an editor.

One of the many drafts.

There were many moments of despair during the preparation process, and several moments of “eureka!” Yusuf Franko was our “man of dark times,” dark times in the sense of the despair and anxiety we have been experiencing in Turkey and in the world intensively for the last couple of years. The humour in Youssouf (the title written on the cover of his caricature album) became one of the strongest motivations and inspirations that helped the whole team hold onto the routine of the work days. He left us a unique material which showed gestures, mimicry, emotion and cunning. Those women and men he drew were real, and we saw them through his eyes; we saw his individuality as much as theirs. He named many of his caricatures by captions, most of them describing directly who the person was. There she was, Madam Stékoulis, in her black dress reading the book titled Life, Virginia Zucchi in her stage costume, and Countess Belmondo holding her man in her palms like Gulliver, or the famous character of the following century, King Kong (Definitely strong women characters! Still, unfortunately, Yusuf Franko’s sister existed in the album only with her husband’s name: Madam Naum Paşa). Yusuf Franko did not only depict people, but he also depicted music and theatre. He depicted great musical instruments and moments of performance, even of a young brother in front of the piano, who died at an early age in Beirut. He depicted the famous actress Sarah Bernhardt rehearsing, and an Armenian musician Mihran Balassan playing the Dance Macabre. But when did he draw all these? Between the years 1884–1896. Yes, but when and how exactly? On a study desk in the evening? During the conferences he attended? Thinking what? Did he smile at his own caricatures after finishing them? Did he hang them on his wall? What was their meaning for him? What was their meaning for the others? What is their meaning for us today? We can speculate about the answers to some of these questions, and the authors in the book brought forth their own interpretations to some of these questions in their articles. They half-opened the gates of a late-nineteenth century bureaucrat’s world and gaze nicely for us. The rest still remains to be imagined, and maybe one day discovered even more.

Yusuf Franko, “L’expiation,” Undated.

I don’t know whether he ever hung them on his wall, but his characters certainly hung him in “L’expiation.” That was the opening of the story of Yusuf Franko for me, and last week this journey reached a new phase in our lives: The last couple of months’ work bore its fruits; the exhibition was opened, the book was published. Feeling the satisfaction of completing a unique project with collaboration, Yusuf Franko “charged” us with smiles on our faces, smiles which we needed very much. The two-volume work was published as a limited special edition by the Vehbi Koç Foundation. I hope, following the exhibition, the book of articles will again have a chance to meet with a wider audience.

Book Citation: Bahattin Öztuncay (ed.) Youssouf Bey: The Charged Portraits of Fin-de-Siécle Pera. Istanbul: Vehbi Koç Foundation, 2016.