Even though it may sound strange or maybe even creepy, visiting cemeteries from time to time, wandering among the tombstones, reading the epitaphs carved for those who are not breathing in this life anymore, has always given me a sense of relief as well as fear, since there is actually nowhere better to show that life is short and pointless and that death is certain.

Whether you are a fellow on Istiklal Street living in the midst of the 24/7 non-stop entertainment culture of Istanbul (which I occasionally—rarely—experience) or an academic struggling to complete articles/books just before deadlines, it is completely normal to forget that life is ephemeral. That’s why I intend to take you out of your busy schedule or your never-ending entertainment cycle and take you on a tour to the cemeteries that remind us of the cold face of death. I will then talk briefly about the stories the deceased narrate in their funerary inscriptions, while comparing them to their ancient counterparts.

A boat trip (on a sunny day if possible) starting from Karaköy ferry port leading to its final destination in Eyüp will take you to one of the most authentic districts of Istanbul and also doubtlessly one of the most historical sites of this gigantic metropolis. Apart from its town center (also worth a visit if you have time), this district houses a very old and famous burial ground (called “Eyüp Sultan Mezarlığı”) on the west bank of the Golden Horn, which hosts the graves of Ottoman sultans such as Mehmed V as well as intellectuals, artists, and poets such as Ahmet Haşim or Necip Fazıl Kısakürek. If you follow the path stretching from the historical Eyüp Mosque up to Pierre Loti Hill (with an exquisite view of the Golden Horn; don’t forget to stop and have tea or coffee if you go there), you will see thousands of tombstones on the slopes of the Karyağdı Hill. Let’s skip the celebrity tombs and take a look at the tombs of the common people.

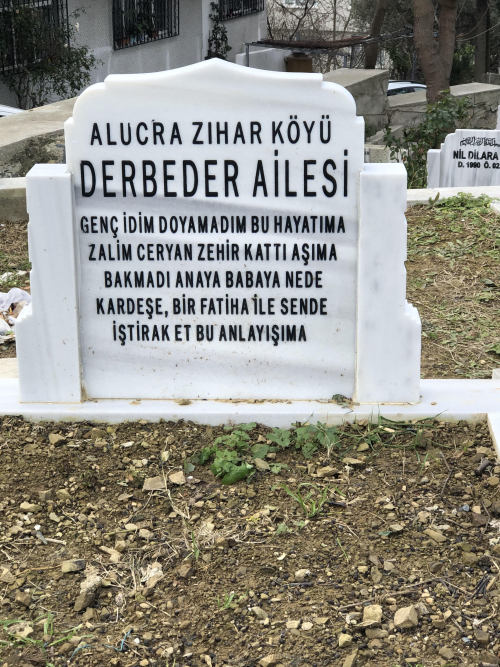

Even though these tombs are from modern Turkey, you’ll notice the same kind of funerary epigrams that were very prevalent in the ancient Greek and Roman world and that provide valuable information about the deceased, containing his mortis causa, place of origin, and the sorrow that his family felt on losing him. This funerary epigram of one member of the Derbeder family, for example, captures the pain of an accidental death at an early age. It reads: “I was young, and I could not enjoy my life; the wretched electricity made my life miserable; it didn’t care about either my parents or my sibling.” This epigram clearly demonstrates that the young deceased was a victim of an electric shock, something nobody could help.

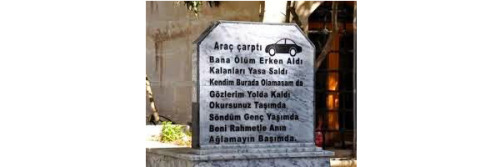

Maybe you don’t have time to visit the cemeteries (understandably enough, but there’s nothing to fear; we will be spending enough time there after our burial), but you don’t even need to bother to leave your room; just surf the internet, for example, and you’ll run into this unusual tombstone.

The epitaph even has a caption: “A car crashed (into me),” along with a picture of a car. The epigram starts with a grammatical mistake (instead of “beni,” it reads “bana”): “Death took me away so early (I came to an untimely end).” Then it goes on like this: “It deeply saddened those who I left behind. Even though I am not present here, I am (still) looking forward to seeing you. Read on my tomb that I died at a young age. Remember me with mercy; do not cry at my grave.”

I don’t intend to make a detailed analysis and comparison, but it is obvious that the expressions or the selections of the themes in these types of epigrams imply a noticeable perpetuity in the approach of the Anatolian people towards the conception of death. However, as a Greek and Roman epigraphist who encounters thousands of texts written in verse, it seems to me that the Anatolian people in antiquity were more creative in producing epigrams than their successors in modern-day Turkey, even though academics adopt the view that “the content of ancient epigrams usually contained standard, and to a large extent previously prepared, compositions which purchasers (often illiterate and/or lacking inspiration, or preferring to adhere to a tradition) could choose at the workshop of the engraver or stonemason.”[1] Take a look, for example, at this remarkably vivid funerary epigram of a three-year-old boy who drowned in a well in Notion, the port of the ancient city of Colophon (Menderes, Izmir/Turkey).

Reinhold Merkelbach and Josef Stauber, eds. Steinepigramme aus dem griechischen Osten I. Die Westküste Kleinasiens von Knidos bis Ilion. Munich; Leipzig: 1998, no. 03/05/04 (Roman Imperial Period):

When the sun had gone down to the halls […],

I came after dinner with my uncle to wash.

At once the Fates sat me there on the well

for I fell in and a most hateful Fate took me away.

When the daimon saw me below, he handed me over to Charon.

But my uncle heard the sound of my falling into the well,

and straightaway he went looking for me, but I no longer had any hope

of mixing with men in my lifetime.

My aunt ran up and tore her gown;

my mother ran up and started beating her breast.

Straightaway my aunt fell to embrace Alexander’s knees,

and when he saw this, he did not hesitate, but straightaway jumped into the well.

When he found me down there drowned, he brought me out in a basket.

Straightaway my aunt snatched my dripping body

to see whether I had any share of life left.

Alas for my wretched fate! I did not live to see the palaistra,

but an evil Fate concealed me when I was just three years old.[2]

In this epigram, one can easily see the significant role that Fate (Gr. Moira) played in the destiny of the young deceased, whose name is not given in the text. Not surprisingly, Fate has always been an indispensable element of funerary epigrams and is usually described as “wretched.” It is repeatedly seen as a leading figure that leaves children without parents or conversely parents without children. In the Turkish epitaph above, although not named directly, we may assume that it was Fate yet again who deprived the parents of their small child, as was the case in the Greek epigram.

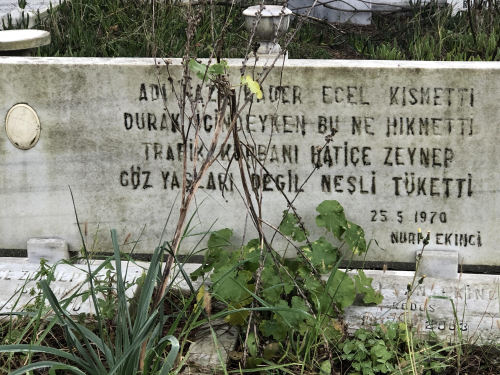

Fate still plays a role in Turkish epitaphs, but because of the Islamic belief that predestination is the will of God and that every believer must consent to what God destines, it doesn’t appear in the same terms as in ancient Greek inscriptions. Unlike the Greek epigrams that describe Fate as ἀμείλικτος, νηλεόθυμος (“ruthless,” “relentless,” or “cruel”), in the funerary stone of this unfortunate lady, who died in a traffic accident (most likely a vehicle crashed into the bus stop and killed her), what happened is characterized as predestination. Every Turkish reader can sense here an acquiescence to death without complaining about what “fate” had in store.

One can provide thousands of similar examples which illustrate how the same themes appear in the funerary epigrams on Anatolian soil across every time period. Admittedly though, it is neither possible nor necessary to make a full comparison between Greek or Latin epigraphic culture and their counterparts in modern Turkey; nonetheless I find it remarkable that the mindsets of the ancient and modern people of the same land could be so similar when it comes to burial practices and ways of grieving.

As a concluding remark, I would like to take this opportunity to commemorate my esteemed teacher, Prof. Dr. Sencer Şahin, who, amongst many other things, taught “ancient Greek epigrams” for many years at Akdeniz University. While we were on a field survey in the hinterland of Antalya years ago, we visited a local cemetery to check if there was anything relevant to our fieldwork. Instead, we saw a very long and interesting Turkish epigram (which bore many similarities with Greek epigram culture, both in form and context; unfortunately I couldn’t find any picture of it). I remember him saying very clearly, “Hüseyin Bey, if you want to pass your exam, I recommend that you study this stone carefully, because you will come across something not very different than this on the exam.”

—————————————————————————————————–

[1] Wypustek, A, Images of Eternal Beauty in Funerary Verse Inscriptions of the Hellenistic and Greco-Roman Periods (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2013), 11.

[2] Translated by Richard Hunter, “Death of a Child: Grief Beyond the Literary,” in Greek Epigram from the Hellenistic to the Early Byzantine Era, edited by M. Kanellou, I. Petrovic, and C. Carey (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 137–38.