This Thursday, November 28th is American Thanksgiving, a holiday affectionately known as “Turkey Day” thanks to the central role the bird has traditionally played on the holiday’s dinner table.

For some, Thanksgiving is a time to reconnect with family and friends with both the usual and unusual fare. For others, it means annual arguments about politics, and for PhD students it may mean dodging questions about your graduation date… But ultimately, when historians are involved at least, the question always comes up: Why do the turkey bird and Turkey the country have the same name?

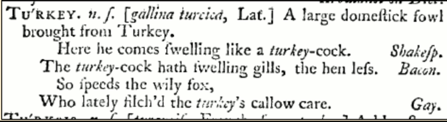

When compiling his 1755 English dictionary, Samuel Johnson defined the Turkey bird as a “large domestic fowl brought from Turkey.” But the Turkey bird is of course not from the Ottoman Empire, an empire that Europeans at the time persistently called “Turkey.”

Samuel Johnson’s famous English dictionary

Instead, its North American origins famously prompted Benjamin Franklin to suggest the Turkey, instead of the golden eagle, as the United States’ national bird.

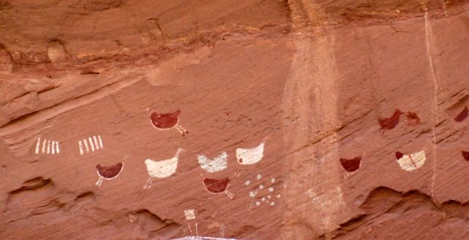

Cave drawings of turkeys in the Canton de Chelly

Before the arrival of Europeans, native Americans on the eastern seaboard of North America hunted the wild Northern Turkey, the Meleagris gallopavo. It was widely used by the Ancestral Pueblo Native Americans. Naturally mummified turkeys have been found at sacrificial spots. Some of these turkeys were domesticated. Archaeologists have discovered evidence of pens made of sturdy sticks where domesticated turkeys were raised for their meat by at least Pueblo I times (750–900 CE). The turkey’s bright feathers were also used for ceremonial robes according to the conquistador Coronado. The bones of the turkeys were also used, carved into tools like awls. The turkey’s role in Pueblo life was central enough even to be immortalized in cave drawings in the Canyon de Chelly.

A mummified turkey in the Canyon de Chelly National Monument.

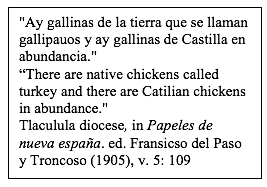

Europeans first encountered the turkey in Central America and Mexico. Hernán Cortés in his 1519 “Letters from Mexico” wrote about “Mexican” turkeys, Meleagris “Agriocharis” ocellate, common in Mexico City before sacking the city. In Columbus’ fourth voyage in 1502 to Honduras, natives presented the newcomers with turkeys which they called gallinas de la tierra, or “land chickens.” Columbus’ Moorish captain Pedro Alonso Niño is believed to have first introduced the turkey to Europe in the early 1500s. Unlike the potato or tomato, the turkey seems to have been a nearly immediate culinary success. By 1530, enough turkeys had been shipped from the Americas to support turkey farms in Spain, Rome, and France.

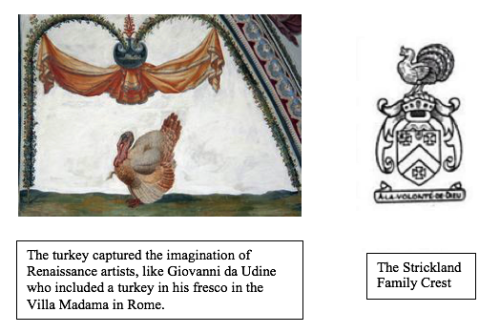

Turkeys first reached England in 1524 through the endeavors of William Strictland, a Yorkshire landowner and a lieutenant on Sebastian Cabot’s voyages. At least, this is a story the Strictlands were keen to promote. With the wealth from his voyages, he purchased a country manor, sat in Parliament, and, in 1550, established a family crest emblazoned with, you guessed it, a turkey! His descendants, however, continue to search for solid proof of Strictland’s celebrated involvement with the introduction of the turkey to England.

Long before Americans adopted turkey as the hallmark of the Thanksgiving feast at the end of the 18th century, the English incorporated the turkey into their own holiday repasts. By 1534, Thomas Tusser had penned verses instructing housewives to provide turkey at their Christmas feast. Henry VIII (r. 1509–1547) himself, an elaborate feaster, is fabled to have offered turkey to his Christmas guests. Archaeologists in Exeter recently dug up turkey bones from one of these early turkey dinners. By 1550 the turkey was already a popular choice for Christmas dinner, and, by 1570, it was a common Christmas dinner selection. Today, according to a recent (and admittedly cutesy) poll, 87% of U.K. residents argue that Christmas just wouldn’t be the same without the turkey.

Yet none of these turkey tales tell us why this North American bird was called the “turkey.” There are a variety of explanations for the conundrum including the improbable and the absurd. Some speculated that the name derived from the red-colored fez even though the fez was only adopted by the Ottoman state in the 19th century. In 1847, one commentator argued for the “resemblance between the head of the Turkey cock and helmet of a Turkish soldier.” Other explanations revolve around English stereotypes of both “Turks” and the turkey bird as proud.

Some linguists argued that the word “turkey” derives from Tamil, a language of South Asia, in which the peacock is called “toka” and reached English through the Hebrew version of the word “tukki.” They argue that Iberian Jewish merchants named the North American bird a “tukki” which through confusion became a Turkey leading people to believe it was actually from Turkey. However, there is no evidence of the involvement of the Jewish diaspora in the Iberian Turkey trade, particularly after the explosions of unconverted Jews from Spain and Portugal in 1492 and 1497.

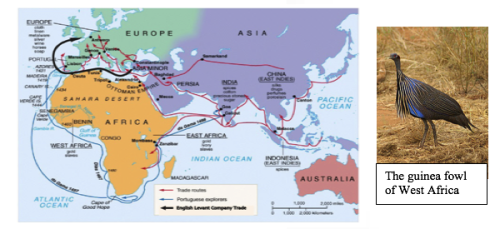

The most convincing explanation for calling the turkey bird a turkey actually involves another bird entirely. The guinea fowl was native to West Africa and traded by Portuguese merchants who, beginning in the late 15th century, were trading around the Cape of Good Hope and into the Indian Ocean. Through Portuguese traders passing through Guinea, the guinea fowl was introduced to the Ottoman Empire. There, at least supposedly, English Levant Company merchants purchased these brightly colored fowl and imported them back to England. They called them “Turkey birds” because they presumed they originated from the place that they first encountered them.

Once the guinea fowl and the turkey were both introduced to England, confusion reigned. Often, they were described as interchangeable. It didn’t help that the Guinea fowl was later exported to the Americas, adding another layer of confusion between the two feathered creatures. Both used the Greek and Latin name meleagris originally reserved for the guinea fowl. When Sir Thomas Elyot wrote in 1552, however, the definition of meleagris had expanded: “Meleagrides birdes,which we doo call hennes of Genny or Turkie henne.” A 1615 recipe book describes guinea fowls as “young turkeys.” As the origins of the two different birds coalesced into one bird with one origin story, the name “Turkey hen” won out. As the Mediterranean terminus of the caravan trade bringing luxury goods from Asia, “Turkey” carried a connotation of luxury and exoticism with which the name guinea fowl was unable to compete.

The bewildering story of how the Turkey bird got its name doesn’t end there. In Turkish, the bird is called hindi. The French similarly called it dinde, from poulet d’inde, “chicken of India.” Armenian, Italian, Polish, and Russian also named the bird after its supposed Indian roots. Dutch, Indonesian, Icelandic, and Lithuanian describe the turkey more specifically as a bird of Calcutta. Why did so many languages insist on the turkey’s Indian origins? Perhaps because the Portuguese traders bringing the guinea fowl to the Ottoman Empire or “Turkey” were most famous for their trade in the Indian Ocean. People just simply assumed it was from India.

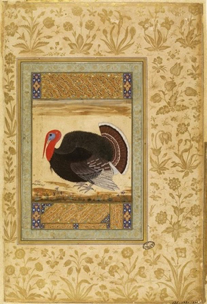

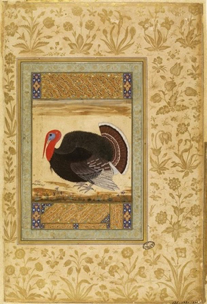

To further complicate matters, in 1612, a turkey brought from Portuguese Goa was presented to the Mughal Emperor Jahangir. By the early 17th century, then, North American turkeys were in India and the Guinea fowl was roaming the Caribbean.

Together, these globetrotting birds—the North American turkey and the guinea fowl—tell a tale of early modern globalization, as more people (and birds!) travelled further and faster than ever before, and the culinary confusion that ensued!

Mughal miniature ca. 1612, attributed to Ustad Mansur.