Dr. Sezer-Aydınlı, Osmanlı kitap tarihi ve okuma kültürü konusunda uzmanlaşmış bir kültür tarihçisidir. Çalışmaları, popüler kahramanlık hikâyeleriyle ilgili el yazmaları üzerine birinci elden notlarına dayanarak Osmanlı bireylerinin okuma, yazma ve dinleme pratiklerine odaklanmaktadır. 2022 yılında Freie Universitat Berlin’den “Osmanlı İstanbulunda Yazma Eserler Topluluğu (18-19. Yüzyıllar): Kahramanlık Hikâyeleri, Sosyal Profiller ve Okuma Alanı”başlıklı teziyle doktor unvanını almıştır.

Tez projesi, Türkiye’deki Amerikan Enstitüsü (ARIT) tarafından 2019–2020 akademik yılı boyunca ABD’deki Boston College’da misafir akademisyen olarak cömertçe desteklenmiştir. Öne çıkan yayınları şöyledir: Osmanlı Edebiyatında Sözlü ve Yazılı: Firuzşah’ın Hikâyesinde Okuyucu Notları (2015) başlıklı kitabın, (2015) ve ”Erken Modern İstanbul’da Sıradışı Okuyucular: Yeniçeriler ve Diğer Ayaktakımının Popüler Kahramanlık Anlatılarındaki El Yazması Notları” (Journal of Islamic Manuscripts, 2018) adlı hakemli makalenin yazarı ve . Osmanlı İstanbulu’nda Sese Dönüşen Kitaplar” (Zemin, 2023)’makalesinin ortak yazarıdır.

Boğaziçi Üniversitesi, Harvard-Yale Üniversitesi, Oxford Üniversitesi ve Princeton Üniversitesi de dahil olmak üzere birçok yerde kamuya açık dersler ve konferanslar vermiştir. ANAMED doktora sonrası araştırmacısı olarak halen “19. yüzyıl Osmanlı İstanbulu ve Anadolusu’nda Popüler Okuma Kültürü” başlıklı projesi ve ikinci bir monografi üzerinde çalışmaktadır.

Popular Reading Culture in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Istanbul and Anatolia

In the 2023–2024 academic year, I was fortunate to have been an ANAMED post-doctoral fellow. The generous support of this institution enabled me to conduct my archival research and present my project on nineteenth-century Ottoman popular reading culture in multiple venues. The collections of manuscripts I have uncovered this year such as storybooks, memoirs, and miscellanies have helped situate popular texts and reading practices developed in nineteenth-century Istanbul and Anatolia in a centuries-old book and reading culture that transcends multiple cultures and geographies (Turkish, Arab, Persian, Urdu).

Fig. 1. A visit to the Rare Book Collection at the Istanbul Research Institute with ANAMED fellows.

The primary source for this research was the popular heroic stories that were circulated in nineteenth-century Ottoman Istanbul via collective reading sessions. Either for scholarly or entertainment purposes, reading stories publicly in front of an audience through the mediation of a prompt text was a widespread reading practice in the pre-modern period. Like their counterparts in Europe or the Near/Middle East, coffeehouses, shops, houses, Sufi lodges, open-air venues… any place where people gathered and socialized could be a venue for collective reading. Led by Istanbul, major Ottoman cities such as Bursa, Edirne, Konya, Sivas, Damascus, and Aleppo hosted collective reading sessions of oral and written narratives. Among them, the stories of heroes from an amalgamation of Arab-Persian and Turkish identities were the most popular texts of these sessions, accompanied by manuscripts as old as thirteenth-century Anatolia.

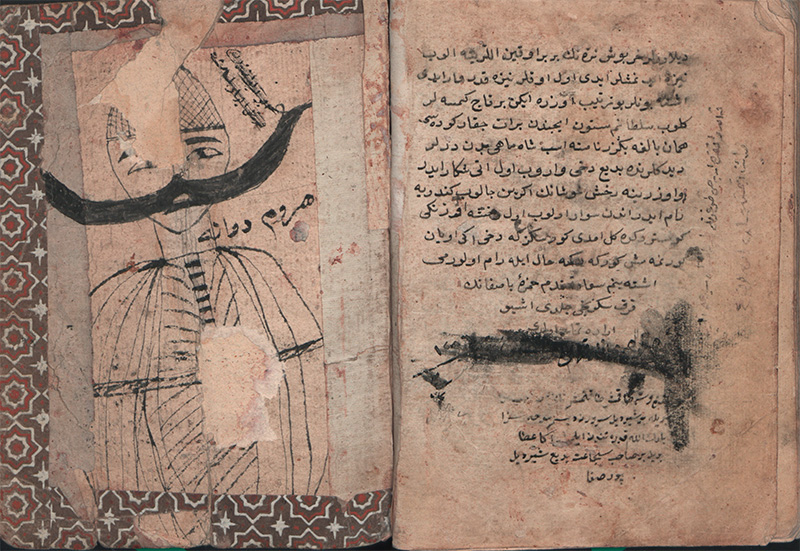

Fig. 2. Sample of a distorted page with a drawing. Hamzanâme, İstanbul, İstanbul Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Kütüphanesi, volume 47, last page.

In the nineteenth century, dubbed the “longest” century of the Ottoman Empire, social structure and urban landscapes changed unprecedentedly, in parallel with transformations in political, economic, and education systems. Likewise, Ottoman reading and writing practices were marked by the introduction of new genres such as realist stories, newspapers, or novels, as well as the dominance of print production. However, the still-ongoing aspects of reading in this period, such as the appreciation of traditional stories, collective reading performances, and production of manuscripts, have not received enough attention in scholarship. Therefore, my primary corpus, the traditional heroic stories produced and widely circulated in the nineteenth century in manuscript format, contributes to a reevaluation of nineteenth-century Ottoman literary culture with specific attention to popular reading practices in Istanbul and Anatolia.

For my archival research during the fellowship term, I sought to enrich the corpus of my doctoral research by including new collections in manuscript libraries. The manuscript collections at the Suna İnan Kıraç Library and Istanbul Research Institute were available for personal as well as collective visits with other ANAMED fellows (Figure 1). I also investigated the manuscript libraries in Anatolian cities such as Konya, Sivas, and Erzurum, thanks to the digitalization of manuscripts and the opening of the Portal by Yazma Eserler Kurumu Başkanlığı. Hundreds of more manuscript notes were written firsthand by their readers about their personal reactions, opinions, and emotions, but their collective reading experiences also enabled me to delve into a widespread cultural practice that especially proliferated in the nineteenth century. The documentary value of these notes comes from the information on addresses, venues, and dates but also the agents of collective reading (kıraat) sessions, of which migrants from the Anatolian provinces composed a substantial portion. Given the scantiness of popular texts that survived in Anatolian cities, this corpus is also precious for pondering the literary tastes and reading practices of Anatolians.

Fig. 3. After my talk with Koç University’s History Club.

During the period of my fellowship, I was able to present the results of my work in multiple venues. I delivered a paper on the interrelationship between the text and reading sessions (meclis) to be published in an edited volume on Ottoman storytelling. In this paper, I discuss how the presumption that eighteenth- and nineteenth-century reading practices became more individual, isolated, and Westernized needs an update. I assert that this period witnessed the emergence of a hybrid reading culture via the overlaps between the text and the majlis, the narrator and the scribe, as well as the reader and the audience. My paper, which I presented at the ERC-supported conference at the University of Bologna, was about these blurred boundaries between reading practices in nineteenth-century Ottoman society through the concept of kıraat. Apart from the reading practices, I also delved into the materialistic aspects of manuscripts in their cultural and historical context. Thanks to my ongoing survey of the manuscripts of heroic stories, I will present a paper at the Center for Manuscript Studies at Fatih Sultan Mehmet University on defacement and auto-censorship practices with a discussion about the intentions of the manuscript users.

I have not only limited my research to the manuscripts of heroic stories but also other sources such as cönks (vertical anthologies), memoirs (hatırat), and miscellanies (mecmuas), to discuss the transformation of Ottoman popular literature by the eighteenth century. In May, I am preparing to present a paper entitled “18th Century Self-Narratives in the Miscellanies of Connoisseurship: Dâyezâde Mustafa, Süleyman Fâik and Saraybosnalı Molla Mustafa.” In this paper, I argue that—due to the new social and cultural environment and the diversification of types of literacy—a new type of miscellany developed in the eighteenth century which is characterized by the use of daily content, vernacular language, and social bonding between authors and audiences. Among the books I reviewed this year, Istanbul-Kushta-Constantinople: Narratives of Identity in the Ottoman Capital, 1830–1930 was also on the diversity of identities and cosmopolitanism in the late Ottoman period through personal narratives of the time.[1] Two other reviews I wrote were 1) on the archival sources of Ottoman literature by İsmail E. Erünsal and 2) on the interrelationship between the manuscript and print cultures in world literature.[2]

I also prioritized presenting my doctoral and current studies to general and semi-academic audiences. The History Club of Koç University invited me to the Sarıyer campus with an interest in my doctoral study. The undergrad students of Doğuş University were also enthusiastic about my study, especially the social profiles of readers and the audiences of heroic stories, during my presentation entitled “Reading (Kıraat) Notes as Sources for Ottoman Social History.” I will also present some outcomes of my dissertation project at the Center for the Study of Manuscript Culture (CSMC) at Hamburg University in June, which is the institution that has awarded me with the J.P. Gumbert Award.

The academic and supportive environment of ANAMED helped me to improve my previous research and embark on new projects. As a non-residential fellow commuting between Üsküdar and Taksim and as a mother of two children, I cannot overstate the impact of ANAMED’s support that inspired and motivated me to make significant scholarly strides on converting my dissertation into my first monograph, as well as the listed secondary projects.

[1] Christoph Herzog and Richard Wittmann, eds., Istanbul-Kushta-Constantinople: Narratives of Identity in the Ottoman Capital, 1830-1930 (New York: Taylor & Francis, 2019).

[2] İsmail E. Erünsal, Arşiv Kayıtları, Yazma Eserler ve Kayıp Metinler: Edebiyat Tarihi Yazıları (İstanbul: Timaş Tarih, 2024); Scott Reese, ed., Manuscript and Print in the Islamic Tradition (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2022).