Anyone who has ever been a fellow or a guest at ANAMED would confirm this: nights here are, undeniably, very animated. Even if you prefer not to join the hyper-intense social life of the local community at Merkez Han, the stream of tourists, musicians, and bon vivants flowing along Istiklal Caddesi constantly remind you how the old Pera neighborhood, although radically transformed over the centuries, has never lost its energetic and cosmopolitan allure.

However, after a certain hour (usually around 3:30 am or so), the ANAMED building seems to fall into a sudden state of calm. Then, only a gentle whistle from the elevators and, occasionally, alley cats fighting in the streets can be heard. That is the moment when bats, introverts, and other eerie creatures of the night are allowed to emerge from the shadows and finally live their moment of glory. It is also, undeniably, the most creative and productive time in the study room on the 3rd floor. Unfortunately, I have always found it extremely difficult to persuade other fellows of that.

ANAMED: the study room at night

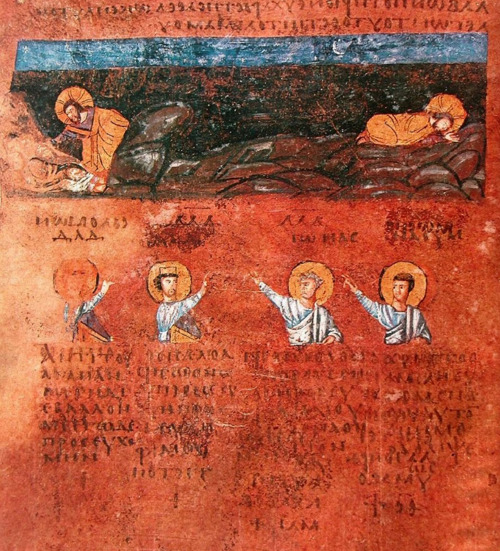

As a Byzantine art historian and a resolute night owl—the two attributes being concurrent, but apparently not consequential—sometimes I love indulging myself with the idea that artists in Byzantium might have shared my personal preference for nocturnal atmospheres. Indeed, for a culture that had developed such a highly sophisticated aesthetic based on the symbolic and soteriological values of light, Byzantium seems to have also cultivated a surprisingly serene relationship with the visualization of the night. Truth be told, Byzantine religious iconography used to associate darkness with some of the most tragic episodes in the Christological narrative, such as the Agony in the Garden and the Crucifixion. In a famous sixth-century representation of Gethsemane from the Rossano Gospels, Christ’s loneliness is emphasized by the presence of a dark background, and the colors are so dense and deep that they permanently stained the parchment on the verso of the same folio.

Rossano Calabro (CS, Italy), Museo Arcivescovile, Codex Purpureus Rossanensis: Agony in the Garden

The night sky, however, often played a positive role in Christian imagery, functioning as a dramatic tool to highlight (pun intended) some crucial moments of the divine revelation and to express the universal potency of God’s nature. The star of Bethlehem descends from a deep blue hemicycle to brighten the darkness of the cave in Byzantine Nativity scenes; golden stars decorate the maphorion of the Theotokos in numerous icons, mosaics, and wall paintings; and in an early seventh-century icon at Mount Sinai, a gleaming, starry night sky surrounds the austere figure of Christ as the Ancient of Days.

Sinai, Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Icon: Christ as the Ancient of Days

Byzantine secular arts also seem to reveal a fascination with the night. Much of this attitude was due to the robust Greco-Roman cosmological tradition, which the Byzantines constantly updated and reinterpreted in their own ways. The luxurious Vat. gr. 1291, a ninth-century copy of the Procheiroi Kanones by Ptolemy, has preserved a calendar table in which the hours of the night, depicted as dark-skinned female busts, surround the chariot of the sun, providing the necessary counterpart to daylight. Another folio in the same manuscript shows a majestic astrological representation of the night sky, in which numerous classical personifications of constellations, delicately sketched in white paint, emerge from a deep blue background.

Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS gr. 1291: Chariot of the Sun/Constellations

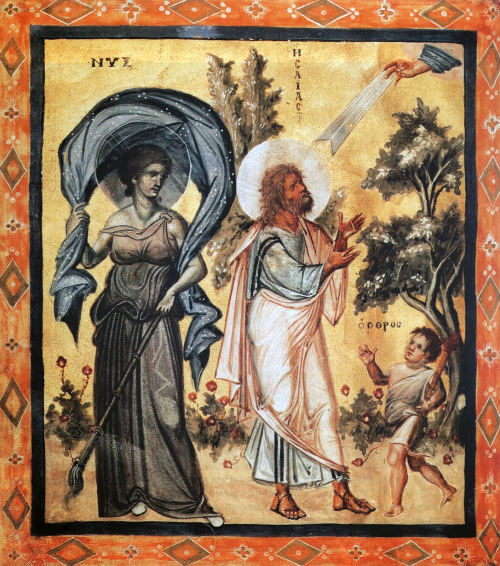

Ancient archetypes contributed to religious iconography, too, and led to some very eclectic (and sometimes curious) results. The well-known Paris Psalter (BNF gr. 139), produced in the mid-tenth century for the court of Constantinople, has preserved some quintessential examples of the enthusiasm for classical imagery that characterized aristocratic artistic production during the so-called Macedonian Renaissance. Among the plethora of Hellenizing personifications that accompany various characters from the Old Testament we can find the elegant Nyx, the personification of the night, depicted as one of the three protagonists in the episode of the Vision of Isaiah. She is clad in a long flowing peplum and her airy blue veil, decorated with little white dots like a starry sky, floats over her head while she gently moves away from the scene, pointing a torch to the ground. The sense of the whole composition is easy to understand: Isaiah’s vision takes place at a very specific moment when the night is slowly making way for the dawn of a new day, Orthros, represented as a cheerful young boy holding a flaming torch.

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS gr. 139: Vision of Isaiah

The representation of the night sky as a precious veil is also included in one of the most notable masterpieces of late Byzantine art in Constantinople. In the Last Judgment scene preserved in the parekklesion of the Kariye Museum (ex-Chora Monastery), visitors can still see the representation of an angel wrapping the starry sky in a roll as if it were an expensive silk fabric, similar to those for which the Byzantine capital was celebrated all over Europe. I have always loved to think of this scene not as an act of destruction but, rather, as an attentive gesture of conservation. The angel is not tearing the sky apart: he is carefully folding and storing away a valuable artifact that is not needed anymore. Another example of Byzantine nyctophilia? Perhaps….

Istanbul, Kariye Museum, parekklesion: Last Judgement, detail