Dr. Böhlendorf-Arslan, Almanya’daki Philipps-Universität Marburg’da Bizans sanatı ve arkeolojisi profesörüdür. Araştırmaları, çanak çömlek, küçük buluntular ve yerleşim arkeolojisi dahil olmak üzere Türkiye’deki arkeolojik saha çalışmalarına dayanarak Geç Roma ve Bizans imparatorluğunun günlük yaşamına odaklanmıştır. Aynı zamanda Geç Antik Çağ ve Bizans kentsel gelişimi üzerine bir proje de yürüttüğü Assos kazılarında görev almaktadır. ANAMED’deki araştırmaları süresince Troas bölgesinin erken hac yerlerinden biri olan Assos Hac Kilisesi ve aziz mezarına odaklanmaktadır. Bu mezar, sıvıların bir kanaldan mezara geçirilmesiyle ikincil kalıntıların üretimi için kullanılıyordu. Antik sur duvarları içindeki erken Bizans kentinin 8. yüzyılın başlarında sona ermesiyle birlikte kilise de terk edilmiştir. Bazen 9. yüzyıldan itibaren ölen çocuklar eski vaftizhanenin bulunduğu alana gömülmüştür. 11. ve 12. yüzyıllarda kilise kapsamlı bir şekilde yeniden inşa edilmiştir. Bu nedenle beklenen yayın, erken dönem Hıristiyan hac yerinin oluşturulması ve bir orta Bizans mezarlık kilisesine dönüştürülmesine önemli bir katkı sağlayacaktır. Ayrıca araştırma, ölü gömme gelenekleri ve anma törenleri hakkında da fikir verecektir.

From Veneration to Commemoration: The Late Antique Pilgrim Church in Assos and its Transformation into a Middle Byzantine Cemetery Church

Beate Böhlendorf-Arslan

West of the ancient city of Assos, in the extended Archaic necropolis street, a church is located on a flat hill (Fig. 1). In the Turkish cadastral plan, this area is named “Ayazma,” even though there is no evidence of a hagisma. However, in the nearby vicinity there are two springs, which may be the name-giver for the church. Since the first excavations of the site in 2002, the building was labeled the “Ayazma church.” Small parts of the remains have always been visible, as seen in the map of the first excavators in 1881.[1] The main building was excavated in 2002 and 2003 under the direction of Ümit Serdaroğlu.[2] From 2007–2012 and with a last campaign in 2022, the church and its surroundings were excavated and examined again.[3] The fellowship from ANAMED in 2022–2023 has enabled the author to work on the publication of the church.[4]

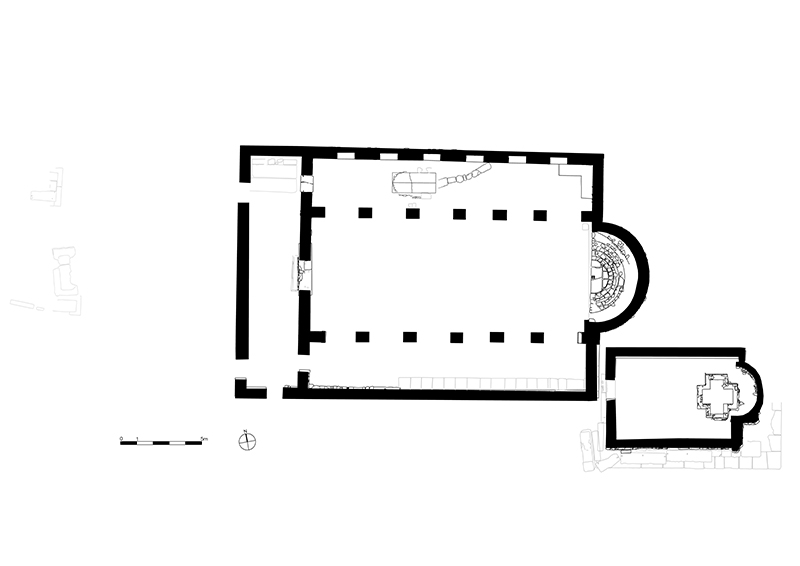

In the south, the Ayazma Church overbuilt two Hellenistic burial terraces in its substructure. In the north, the rocky ground was cut and straightened. The church was first constructed in the sixth century as a three-nave basilica with a round apse in the east (Fig. 2). The early Byzantine basilica was divided into three naves by a row of columns; the postaments of the column are still preserved in the masonry of the later building. Probably, the first church also had a narthex, even though the narthex visible today was built later in the Middle Byzantine period. The interior of the church was furnished with a mosaic floor, of which small remains are still preserved. A small baptistery to the east of the southern nave, built directly on the massive Hellenistic burial house, hosts a cruciform font used for the baptism of the first Christians. The early Byzantine church houses a burial pit in the northern nave. The grave, measuring 1.6 x 1.6 m, was dug into the rock of the church and covered with a reused Roman sarcophagus lid. In this tomb, a venerated person was buried, a saint or martyr, as shown by a channel covered with flat stones leading into the tomb coming from the northeast. Such installations were used for the infusion of liquids such as oil or water, which become secondary relics through contact with the sacred body. At what time this tomb was built and who was buried here is unknown. There are no references to a saint in Assos in the historical sources. Similar installations for the production of secondary relics date back mainly to the fifth century.[5] Until the end of the seventh century, simple bronze tubes were produced in the xenodocheion and used to cover the holy relics from the church.[6] The building was gravely affected by the devastating earthquake that also destroyed the early Byzantine city in the end of the seventh century.[7]

The holiness of the church was never forgotten by the inhabitants of Byzantine Assos. Since the ninth or tenth century, the former baptistery was used as a small burial ground. Afterwards, in the eleventh century, the building was rebuilt in the type of church with isolated aisles.[8] This new church was used for liturgical proposes, as demonstrated by the massive ambon in the center of the naos and the bema, separated by a templon.[9] The floor of the naos was paved with sarcophagi cut into slabs, on some of which the early Byzantine inscriptions can still be seen. On the sides, stone benches lean against the walls. The bema was covered with marble slabs, small remains of which can still be found. The screed on which the slabs were laid shows the size of the slabs and the position of an altar. An atrium was built in front of the narthex to the west. Several high benches made of reused and trimmed sarcophagus slabs were used in that area to lay out and present the dead (Fig. 3). To the east of the apse, a narrow funeral chapel was added, using the north wall of the former early Byzantine baptistery as a foundation for the southern wall of the burial chapel. Only children were buried in the chapel and in the area around it.[10]

In the twelfth century, the church was rebuilt for the second time. The church was now converted into a cemetery church. The atrium was divided, and a burial chamber was built in the northwest. In the southeastern corner of the church, a small parekklesion in the shape of a dome-in-cross-church was added. The entrances in the west of the naos into the side rooms were closed with masonry. The side rooms were divided with walls and now served as burial chambers. The saint’s grave was still venerated at that time; the burials ad sanctos date back to that time. The attraction of the unknown saint was possibly also the reason as to why people then buried their dead in and around the entire church in the twelfth century.

References

Böhlendorf-Arslan, Beate. “Assos. Bericht Über Die Ausgrabungen Und Forschungen Zur Stadtentwicklungsgeschichte 2006 Bis 2011.” Archäologischer Anzeiger 1 (2013): 228–38.

Böhlendorf-Arslan, Beate. “Die Ayazmakirche in Assos. Lokales Pilgerheiligtum Und Grabkirche.” In Assos: Neue Forschungsergebnise Zur Baugeschichte Und Archäologie Der Südlichen Troas, edited by Nurettin Arslan, Eva-Maria Mohr, and Klaus Rheidt, 205–20. Asia-Minor-Studien 78. Bonn: Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, 2016.

Böhlendorf-Arslan, Beate. “Pilgerdevotionalien Aus Assos?” In Contextus: Festschrift Für Sabine Schrenk, edited by Sible de Blaauw, Elisabet Enß, and Petra Linscheid, 446–51, Taf. 67. Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum Ergänzungsband 41. Münster, Westfalen: Aschendorff Verlag, 2020.

Böhlendorf-Arslan, Beate. “Transformation Von Stadtbild Und Urbaner Lebenswelt: Assos in Der Spätantike Und in Frühbyzantinischer Zeit.” In Veränderungen Von Stadtbild Und Urbaner Lebenswelt in Spätantiker Und Frühbyzantinischer Zeit: Assos Im Spiegel Städtischer Zentren Westkleinasiens, edited by Beate Böhlendorf-Arslan, 23–90. Mainz: Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums; Propylaeum, 2021.

Buchwald, Hans. “Christian Basilicas with Isolated Aisles in Asia Minor.” In Architektura Vizantii I Drevnej Rusi IX–XII Vekov: Materialy Meždunarodnogo Seminara; 17–21 Nojabrja 2009 Goda, edited by D. D. Ëlšin, 35–57. Trudy Gosudarstvennogo Ėrmitaža 53. Sankt-Peterburg: Izdat. Gosud. Ėrmitaža, 2010.

Clarke, Joseph Thacher, Francis Henry Bacon, and Robert Koldewey. Investigations at Assos: Drawings and Photographs of the Buildings and Objects Discovered During the Excavations of 1881–1882–1883; Expedition of the Archaeological Institute of America. London: Quaritch, 1902/1921.

Comte, Marie-Christine. Les reliquaires du Proche-Orient et de Chypre à la période protobyzantine (IVe–VIIIe siècles): Formes, emplacements, fonctions et cultes. Bibliothèque de l’antiquité tardive 20. Turnhout: Brepols, 2012. Teilw. zugl. Paris, Univ. IV, Diss., 2006.

Dennert, Martin. “Außerstädtische Kirchen in Assos in Frühbyzantinischer Zeit.” In Veränderungen Von Stadtbild Und Urbaner Lebenswelt in Spätantiker Und Frühbyzantinischer Zeit: Assos Im Spiegel Städtischer Zentren Westkleinasiens, edited by Beate Böhlendorf-Arslan, 153–70. Mainz: Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums; Propylaeum, 2021.

Donceel-Voûte, Pauline. “Le Role Des Reliquaries Dans Les Pèlerinages.” In Akten Des XII. Internationalen Kongresses Für Christliche Archäologie: Bonn, 22.–28. September 1991, edited by Ernst Dassmann and Josef Engemann, 184–205. Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum Ergänzungsband 20,1. Münster: Aschendorff, 1995.

Serdaroǧlu, Ümit. Assos: Behramkale. Istanbul: Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yayınları, 2005.

[1] Joseph Thacher Clarke, Francis Henry Bacon, and Robert Koldewey, Investigations at Assos: Drawings and Photographs of the Buildings and Objects Discovered During the Excavations of 1881–1882–1883; Expedition of the Archaeological Institute of America (London: Quaritch, 1902/1921), 13.

[2] Ümit Serdaroǧlu, Assos: Behramkale (Istanbul: Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yayınları, 2005), 110–17.

[3] Beate Böhlendorf-Arslan, “Die Ayazmakirche in Assos. Lokales Pilgerheiligtum Und Grabkirche,” in Assos: Neue Forschungsergebnise Zur Baugeschichte Und Archäologie Der Südlichen Troas, eds. Nurettin Arslan, Eva-Maria Mohr, and Klaus Rheidt, Asia-Minor-Studien 78 (Bonn: Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, 2016), 205–20; Martin Dennert, “Außerstädtische Kirchen in Assos in Frühbyzantinischer Zeit,” in Veränderungen Von Stadtbild Und Urbaner Lebenswelt in Spätantiker Und Frühbyzantinischer Zeit: Assos Im Spiegel Städtischer Zentren Westkleinasiens, ed. Beate Böhlendorf-Arslan (Mainz: Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums; Propylaeum, 2021), 153–70, esp. 153–58. This project was carried out together with Martin Dennert (Freiburg/Marburg) with the help of Bilge Bal and Christof Hendrichs. The project would not have been possible without the support of the excavation director Nurettin Arslan and the Turkish and German excavation teams. I would like to take this opportunity to once again express my sincere thanks to all those involved in the project.

[4] I would like to take this opportunity to thank the entire ANAMED team for this great opportunity.

[5] Marie-Christine Comte, Les reliquaires du Proche-Orient et de Chypre à la période protobyzantine (IVe–VIIIe siècles): Formes, emplacements, fonctions et cultes, Bibliothèque de l’antiquité tardive 20 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2012; Teilw. zugl. Paris, Univ. IV, Diss., 2006), 116–18; Pauline Donceel-Voûte, “Le Role Des Reliquaries Dans Les Pèlerinages,” in Akten Des XII. Internationalen Kongresses Für Christliche Archäologie: Bonn, 22.–28. September 1991, eds. Ernst Dassmann and Josef Engemann, Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum Ergänzungsband 20,1 (Münster: Aschendorff, 1995), 184–205, esp. 188–200.

[6] Beate Böhlendorf-Arslan, “Pilgerdevotionalien Aus Assos?” in Contextus: Festschrift Für Sabine Schrenk, eds. Sible de Blaauw, Elisabet Enß, and Petra Linscheid, Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum Ergänzungsband 41 (Münster, Westfalen: Aschendorff Verlag, 2020), 446–51, Taf. 67.

[7] Beate Böhlendorf-Arslan, “Transformation Von Stadtbild Und Urbaner Lebenswelt: Assos in Der Spätantike Und in Frühbyzantinischer Zeit,” in Veränderungen Von Stadtbild Und Urbaner Lebenswelt in Spätantiker Und Frühbyzantinischer Zeit: Assos Im Spiegel Städtischer Zentren Westkleinasiens, ed. Beate Böhlendorf-Arslan (Mainz: Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums; Propylaeum, 2021), 23–90, esp. 82.

[8] Hans Buchwald, “Christian Basilicas with Isolated Aisles in Asia Minor,” in Architektura Vizantii I Drevnej Rusi IX–XII Vekov: Materialy Meždunarodnogo Seminara; 17–21 Nojabrja 2009 Goda, ed. D. D. Ëlšin, Trudy Gosudarstvennogo Ėrmitaža 53 (Sankt-Peterburg: Izdat. Gosud. Ėrmitaža, 2010), 35–57.

[9] Beate Böhlendorf-Arslan, “Forschungen Zum Spätantiken Und Byzantinischen Assos: In: N. Arslan / K. Rheidt (Eds), Assos. Bericht Über Die Ausgrabungen Und Forschungen Zur Stadtentwicklungsgeschichte 2006 Bis 2011,” Archäologischer Anzeiger 1 (2013): 228–38, esp. 230–32.

[10] (Böhlendorf-Arslan 2016, 212–13