Dr Gülhan Erkaya Balsoy (Associate Professor) and Dr Başak Tuğ (Assistant Professor) are two scholars who have made important contributions in the field of gender in Ottoman history, but they were also ANAMED’s junior fellows during the 2006-2007 academic year. Today, Balsoy and Tuğ are both faculty members at Bilgi University’s Department of History, and their respective PhD theses, which were in part written at ANAMED, have recently been turned into two prominent books.

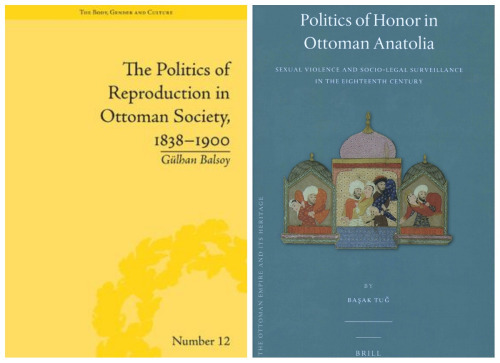

Balsoy’s book The Politics of Reproduction in Ottoman Society 1838-1900 was published by Pickering & Chattoo in 2013, later translated into Turkish under the title Kahraman Doktor İhtiyar Acuzeye Karşı: Geç Osmanlı Doğum Politikaları (The Heroic Doctor versus the Old Crone: Late Ottoman Birth Policies), andpublished by Can Publishing House in 2015. One of the best and most heart-warming developments of last year was that the book received the Yunus Nadi Social Sciences and Research Prize. Tuğ’s book, Politics of Honor in Ottoman Anatolia: Sexual Violence and Socio-Legal Surveillance in the Eighteenth Century is hot off the presses. It was printed by Brill Publishers, and has already become one of the most important resources for examining the 18th century history, which is not particularly well known, especially from the perspective of gender.

In the ANAMED terrace, which is familiar territory for them, we talked with Balsoy and Tuğ about their work, their fellowship years at ANAMED, and the developments that took place since that time in field of Ottoman gender history in Turkey.

Interview: Özge Ertem, ANAMED Editor and Publication Coordinator

Ö.E.: First, I would like to thank you both for agreeing to do this interview. The fact that we are now speaking on ANAMED’s terrace has a pleasant precedent as well. In 2007, when I was yet at the beginning of my PhD studies, I first met ANAMED through one of the “ANAMED Fellowship Mini Symposia” panel sessions, during which you spoke about “Petitions in the Ottoman Empire.” I had come to listen to you, was quite impressed, and learned a lot. Exactly 10 years have passed since. During this time, much has changed in our personal and social history. Of course, your research has also been through a journey. We shall mention these later. I would first like to go back to those days. What sort of an experience was it to be a junior fellow at ANAMED? If ANAMED has made some contribution to your work, what was it?

GB: In my case, it has made a direct contribution. In May 2006, I completed my PhD competency requirement, and I arrived in Turkey to make use of the archives during the summer. (During her fellowship, G.B. was a PhD student in the History Department at Binghamton University.) As I started my PhD dissertation, I had another topic in mind. Later as I got to use the archive, I realized that the topic in question did not excite me, and that I did not want to write about it. Working on gender had always been on my mind, hence everything took place for me right here. Spending time in the archives as though it were a 9 to 5 job was nice indeed, and a great luxury as well. At the time, it may have seemed like a drag, but as you look back, you say “what a pleasant time that was indeed.” All you do is research. Working in this fashion does have its difficulties; but it is possible to beat the loneliness of the research process by chatting, by sharing, by consulting with others who are on the same boat. Academically, it has got that kind of an equivalent. That presentation that you mentioned, I think we did it around April. It was the spring semester, and the major part of my archive work was about finished. I gathered that material and presented it here for the first time. I was not convinced about the presentation until the last minute. Yet, when I think about the preparation itself, and the reactions I got there, I see that ANAMED contributed a lot in terms of shaping my research. But making a debut is quite critical (laughter); you just do not know. For me it was the basis of my PhD thesis, it was the very beginning, and there was nothing before. At the end of one year of research, I wrote the first section of my thesis. That section never ended up in the thesis but served as a scratchpad, a thinking tool. “How will I formulate this, how will I turn those choppy archival documents into a consistent narration, what do I do with them?” It is thanks to this bickering that the thesis could emerge.

B. T.: My situation was a bit different than Gülhan’s because I had come before for my PhD research. (During her fellowship, Başak Tuğ was a New York University PhD student.) My topic was decided on as well. For me, this was more of place where I got my writing process done. I was living here as well; the advantage is that you are here with people night and day, you occasionally “shoot the crap,” but you still get to discuss your topics, you share your writing, at night you sit up, when you need to you work with the others until late hours. We read documents together. For me, the ANAMED Library was the first place where my thesis emerged. Amy Singer was here at the time, one of our senior fellows, and this is what she’d always say to us: “Guys, make the most of this period, afterwards you will never have free time like this.” She was really a hard worker. She would wake up at 8:00 AM, and worked non-stop until 21:00. We followed her example, “let’s work, there won’t be such an opportunity later” we thought. Indeed, in the aftermath we saw that there was no time (laughs). In that sense, it was a very nice and precious time. We had participated in excursions organized by archaeologists, by architectural history experts. While an issue was being discussed, I benefited a lot from hearing comments from people from different disciplines.

G.B.: When I got the scholarship, Donald (the late Professor Donald Quataert) said, “Look, you applied for a scholarship and you got in. You are very lucky, but chances are you are not aware of this. So, make best use of it, as this is a very rare opportunity.” Later, I really understood what he meant. He was right.

Ö.E.: At this point, I would like to move the discussion to your books a bit. While Gülhan focuses more on the birth and health politics of the state in the 19th century; Başak, you focus on the establishment practices of sexuality and gender on the legal and moral plane in the 18th century. As gender historians, one of you is studying the 18th century, and the other the 19th. What do you have to say about the dynamics of working on the gender question at these different periods?

B.T.: As a person who has studied 20th century history, the first years of the republic, in my previous master’s thesis, I decided to work on early modern society, which we can also call the transition period. Previously, we had always read the state through the questions “how does the modern state control, how does it regulate?” Thinking about the early modern society not only creates a great change in terms of sources but also requires moving to another mental plane, requires questioning our own assumptions. Being able to step outside of that framework, and being able to imagine something else has been educational for me. As researchers, as historians who study the early modern period, we have very few materials. With few materials, we work in a field that requires a lot of imagination. Sometimes, I am jealous of the abundance of material in the 19th and 20th centuries (laughter). I had feelings like “I wish there were more materials, I would experience less strain.” But to the contrary, I felt this as well: When you work with such few materials your creativity, your capacity to play with text increases.

G.B.: I agree a lot. I had a dream of gendering history in the context of the 19th century; but in effect, I [we] end up getting stuck on the question of the “nature of the state.” As much as I try to give women voices by looking at the population policy, and try to think about how women can be rendered agency as historical subjects, as a researcher of the 19th century, I end up thinking about the state quite a lot. It is an important hurdle. The documents we use also tend to force this upon us. We use archival documents, which are already prepared from the viewpoint of the state. We try to deal with a narration by questioning the state a bit, yes, asking those questions is valuable. But it becomes quite tricky to get out of that considering that even the material is permeated with the state. Hence, I believe that studying the 17th and 18th centuries could be an advantage to break this hurdle. Therefore, quite to the contrary I am jealous of that aspect sometimes (laughter).

B.T.: But your field does have its advantages.

G.B.: Sure, yes. I mean, abundance of material is a mixed blessing. There’s so much more material; but that same material does occasionally lead to reductionist comments. Or because the material itself is fascinating sometimes wonderful things can emerge as well, at that time one may forget to question. Hence, it’s always a two-sided phenomenon, but the issue of material is always a two-sided phenomenon for the historian anyways.

Ö.E.: In your respective studies, the concept of power holds a prominent place. In between these two periods, what kind of change or continuity can be discussed between power and woman’s body?

B.T.: Certain 19th century historians claim that there are many breaks. The most important thing in the discourse of modernity itself is already the idea that, “revolutions create breaks and everything changes.” But when we look at changes in Ottoman society, especially into the construction of gender, when we consider the reflexes of the state, I think that there’s a great deal of continuity between the 18th and the 19th centuries.

G.B.: In my opinion, the most important claim of the gender concept is that “it makes history different, encourages to think differently.” I agree with Başak, we do see that there is not that much of a radical break between centuries. Using the concept of gender as a tool of analysis reminds us that we cannot really wall up and separate centuries. Hence the materials are different, the issues that we can dig up are a bit different, but gender is a strong concept which reminds one of continuity itself. It also makes it possible to question state controlled understandings of history as well. In that sense, perhaps our biggest advantage comes from the method that we use.

Ö.E.: Gülhan, why does the “heroic doctor face the old crone”? How does “the old crone” cope with this situation, and when a woman is in need which one does she go to? How do you access the woman’s voice while looking for answers to these questions?

G.B.: It was the publishing house that wanted the title, but I liked it too (laughter). This was the subheading of the book. The concept of the oldcrone is one that 19th century physicians use a lot. It appears especially frequently in Besim Ömer’s books, who is the founder of midwifery, of the education of midwifery: “Dirty, nasty, old, ignorant, understands nothing, causes deaths, feels no remorse…” Besim Ömer draws a gruesome picture of the midwives, and constantly uses the term “crone.” He thinks that young mothers put up with these women only because of ignorance. On the other hand, there’s the concept of the physician who is educated, modern, knowledgeable, conscientious, protective of children, and truly very ideal. Sure, in this context the prototype of the heroic physician is Besim Ömer himself. As the first modern gynecologist, the person who started the education of midwives, who wrote the history of medicine, Besim Ömer embodies all those heroes. That is the irony that I was trying to point out there. As to the midwives, remember when we spoke about sources being limited… finding the voice of the midwives has not always been easy. Archive documents tend to contain indirect things. Because of documents such as şehadetname (testimonial), education and the like, the archives allow us to hear about midwifery, about the regulations relating to the profession rather than the voices of the midwives themselves. But it is still possible to reach a few things relating to the midwives from there. There, a picture much more colorful then Besim Ömer’s black and white portrayal emerges. Midwives sometimes reach compromises amongst themselves, sometimes they do not. On the one hand, the institution of midwifery is being put under regulation through şehadetname documents, but on the other hand, it is exactly because of this regulation that they acquire other advantages. They get to write petitions and request certain things from the state, at times they quarrel amongst themselves. Hence, I think that we can see the dynamism of the day-to-day life rather than a picture where they are completely passive. It must be considered that being a historical subject lies within that dynamism. When we talk about being the subject of history, we historians always try to see major strategies, major resistance, major clamor… Often times, in the story of “ordinary people,” there are situations from daily life, which sometimes involve efforts of adaptation, of deriving benefits, of using something to good account rather than major rebellions, disobedience and the like. And inside this dynamism is the thing called agency. While writing the first thesis, this was a bit of thing I idealized (laughter). I ran a bit into a wall there. Within the chaos in everyday life, there is an area that the historian can see or open a crack in the wall to allow the light to pass through. That’s why, the historian may find something exciting in those tiny beams rather than those massive acts of resistance.

As to the question of the relationship between women and midwives, in the 19th century the number of physicians who are graduates of medical schools is still very low, hence births are for the major part handled by midwives, especially in rural areas. Doctors are prominent only in large urban areas. Practicing midwives acquire the document entitled “şehadetname.” In the beginning—perhaps I can think about it in terms of the evolution of my own historianship—in my own mind there was the notion that “the doctor is worse; the midwife is better.” But especially afterwards, during the study I conducted on the Haseki Hospital, I saw this as well. Women who would otherwise be dead, who underwent difficult labor, are sometimes saved thanks to the intervention of doctors. Hence when this is reduced to “the doctor took total control of the woman’s body, made her passive,” a plain picture emerges there. At that point, I started thinking a bit more about the issue of catching the dynamism of daily life again. There was a case in Haseki Hospital; a woman had failed to give birth for a long time, for 8 days. Her baby died and, later the doctor intervenes with a C-section and manages to save the life of the mother. If a hospital had not been established there, if that physician were not there and if those medical changes did not take place, that woman’s life would most likely not been saved. I think the issue needs to be studied in its various aspects.

Ö.E.: Başak, in the context of your topic, how does the voice of the woman emerge especially in the adultery and rape petitions sent to the Divan? How does the woman herself manifest in the legal space where decisions directly related to her body are taken and precedents take shape? How do law and everyday life intersect or intertwine in the specific case of gender?

B.T.: Because I deal with the issue of law and because I am interested in it, in the thesis and in the book, I highlighted the section on the petitions that the people of the Ottoman Empire and especially women could send in Istanbul. Of course, that is not the only area that women use. In practice, they most frequently use the local “kadı” (Muslim judge) courts. In the petitions, in the relationship established with the state, again there is a usage that we cannot establish upon two oppositions. It is mostly men who enter a relationship with the big “father,” with “the father state.” In general, their voices are stronger there. They have more access to Istanbul. They speak a lot on behalf of women, they submit many petitions that state, “My wife, my daughter has been subjected to violence,” and the like. But, incredibly sometimes women manage to make their voice heard in situations where they cannot make their voices heard locally. The woman does all she can, and insists, and convinces the local court or local administrators to refer her case to the central authority. Hence, we cannot find the autobiography of the woman directly, but we can see that she tries to make her voice heard in other areas and that she is successful. Of course, they are less powerful in the legal area. According to Islamic law, in issues such as equality of the genders, they are already seen as a lower class, but there are also some rights that are being provided by the same Islamic law. They manage to use these rights. That was the thing that was interesting for me; legal rules are nothing, but you need to master the phase concerning how you will play with those rules, how you will use them. Women manage to show this mastery. What is more, which is quite interesting, they show it better because they are powerless. They end up having to act wiser so that they can execute all those maneuvers, because they already have next to nothing to lose. It is not in vain that women today need to act much smarter (laughter). It’s a result of powerlessness.

Ö.E.: You both explain that the establishment of gender is a political issue. You base this on that biology and law are not given categories, that they are in fact areas with extreme conflicts. As historians of gender, when you look at today, does the woman’s body have a similar appearance from the perspective of law and health policies?

G.B.: When considering directly through the topic I am studying, the issue of having children has turned into a very current affair today along with birth-related policies. In 2006, at the time I started researching the issue, the “three-children” policy did not exist. Actually, I did wonder “if it did exist, would I set out to research this?” (laughter). I might have been a bit afraid of the domination of everyday life. This policy became a vivid reminder of the appropriation by political power of a woman’s body and birth. The state of the 19th century and the state of today say “give birth,” but they do not necessarily have to. In fact, states intervene not by saying “give birth” but “do not give birth”—an example being the one-child policy in China—through methods that limit fertility. Not necessarily encouraging birth and fertility, but certain methods of birth, by creating discourses about how to give birth… Debates concerning C-Section, abortion are widespread not only in Turkey but also in the United States. The state intervenes in various ways, sometimes involving daily policies that are in opposition to one another. The intervention itself is an issue with a lot of history.

B.T.: From time to time I also think, but I am against drawing too many parallelisms with today. For example, during the recent debate concerning the draft law on sexual abuse and the age of consent, many references were made to Islamic law via the issues of early marriage and child marriages. Hence a kind of expertise area emerges. “How was it in Islamic law? How is it in modern societies? How is it in terms of human rights?” In my opinion, how it is in terms of human rights should be discussed. I think that the use of an Islamic law debate for legitimizing or criticizing arguments through statements such as “even in Islamic law it is such” or “this was better even in Islamic law” is quite essentialist. We need to be able to conduct those debates without falling into essentialism. Hence, I cannot establish a connection between my field and the debates that are ongoing today. It seems to be that the only parallels we can draw between the 18th century and today, is to point out how much women are being oppressed.

Ö.E.: The two of you have also hosted last year’s Gender History debates at the Tarih Vakfı (The Economic and Social History Foundation of Turkey) where historians who work on gender have delivered great speeches. Based on these, I would like to ask you this question: In the last decade, from the days of your ANAMED fellowship until today, what sorts of developments and changes have taken place in Turkey, in Ottoman gender history? Where have social gender studies come to?

B.T.: When we started, gender studies already existed in Turkey, in sociology and political science. In our field, at least from what we can see from our students, there’s increasing interest in the history of gender. Hence, we are happy. But when we look in terms of departments, ours (Bilgi University’s Department of History) is almost the only department where a two-person majority is studying gender (they laugh). Occasionally, we have students that we would like to refer to other institutions. And when we try to think of “institutions specializing in gender in the historical field,” we cannot find any. Often, we direct students to sociology and to political science. This situation still needs development.

G.B.: Indeed, there are very few, especially in Turkey. But in the world as well the field of gender still sits a bit on the periphery of history. I think in the last decade excellent articles and books have been published. The number of people who work on these issues, the number of interested students increased. I think this is quite important. A lot of road has been covered both in terms of questioning political power, and in terms of gendering history.

B.T.: Only the history of woman is no longer being made.

G.B.: Good studies in woman’s history and biographies have emerged. Its visibility also increased. I am very optimistic on this issue, especially concerning the young generation. The upcoming generation thinks about history differently.

B.T.: There are more people who want to do masculinity studies as well. That’s also an important development.

Ö.E.: Non-Muslim women, women from other classes, there is a lot of research on these groups that has started being published, right?

G.B.: Yes, additionally there is no required course on gender, but if we were to open one I think students would be interested and take it, because during the weeks we cover gender in our Ottoman history courses, even students who are not interested at first, later say they encounter questions they never thought about. And this makes you feel good. My own questions and perspective have also changed in these ten years. When I first started writing the thesis, I was preoccupied with “the subjectivity, strength, voice, visibility of the woman.” Now, I also see that women have had a much stronger potential without necessarily having to shout. It’s not something I discovered, as those people who study social history already point this out, but I now see this much better in terms of my own study. Individuals make tiny tiny choices, and this is where the human being is established. Not necessarily in the major actions that you participate in, but in the trivial things that you do.

Ö.E.: As we wrap up the interview, as ANAMED’s PhD fellows of 10 years ago, what would you like to say to ANAMED’s future junior fellows?

B.T.: They should make the most of their time here. That was a beautiful time. It is an utopic situation. A time that will most likely never occur again.

G.B.: Yes, it was really a great luxury to be able to focus only on your research for a whole year, without having to teach, without having to work. They should enjoy it. Later, especially when teaching starts, unfortunately there’s never such free time.