We are all going through extraordinary times. The Covid-19 pandemic has forced us to change our daily routines and lifestyles and adapt to a mostly home-based life supported by digital technology that enables us to continue working and keep in touch with friends and colleagues. For us as ANAMED fellows, this had a relatively devastating effect as we suddenly lost a lively research environment which we all enjoyed and from which we all benefited at a level one rarely experiences. Being a residential ANAMED fellow also meant living in Beyoğlu and experiencing the bustling and cheerful life along İstiklal Caddesi at the social heart of Istanbul, which used to be a place full of people almost 24 hours a day. İstiklal and parts of Beyoğlu surrounding it are now more or less deserted except for the members of the working class, who struggle to keep the service industry functioning as they have noother alternatives. Staying or working from home is sadly not an option for them, and life continues as it has always been.

Although this is the first time we are directly facing a pandemic in our lives and witnessing its devastating effects, we all knew that epidemics and pandemics took the lives of entire populations, caused socio-economic systems to collapse, and left deep marks on the cultural memories of people throughout history across the globe. As my research focuses on the Ancient Near East, I decided to look back at how deadly outbreaks in the region’s distant past—the earliest attested written records of epidemics we can refer to—were described, hoping that we can relate to them in these hard times.

Ordinary people did not mean much to the ruling classes of ancient states of the Near East. They were vital for the economic and socio-political systems to function, but they were more or less seen as masses that were created to serve the political and religious elite, work all their lives under severe conditions under the pretext of obeying and serving the gods, and had no rights whatsoever. Once an epidemic hit the land, these people deemed unimportant were the first to become victims, but losing too many of them meant economic depression and, in some cases, the collapse of the whole system. People did not really know how deadly bacteria and viruses functioned, and these diseases with such huge impacts could only be explained with reference to some sort of divine intervention or the wrath of gods, to be more specific. It was widely believed that supernatural beings spread such diseases, in a way possessing people and causing them to die, and so people sought the help of other supernatural beings or deities in these situations.[1] So instead of wearing masks and adopting “social distancing,” they prayed, conducted rituals, and wore protective amulets, hoping that these would keep the malicious beings that brought diseases away from them.

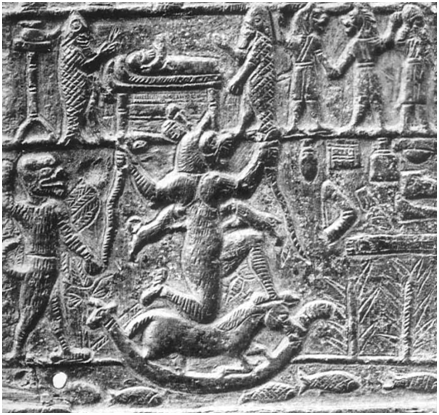

Detail of an ancient Mesopotamian amulet showing a sick person, priests, and a demon.

Various Sumerian texts from the end of the third millennium BCE from southern Iraq mention symptoms of diseases and possible epidemics.[2] These texts talk about people having difficulty breathing, and having contorted faces and twisted muscles because of diseases that spread with the wind like a storm, in one case originating from a distant land and in another asking it to return to its home. People cry with pain and feel helpless as they have no remedy and lose all their loved ones. The texts also refer to economic problems that made things even worse, such as famine, another calamity people had to face at these times of trouble. These epidemics were defined as destroyers of cities, causing masses to die.

The earliest mention of an epidemic from Turkey can be found in Hittite texts from central Anatolia. King Murshili II talks about a 20-year epidemic in the 14th century BCE that took the lives of two kings and many subjects, blaming Egyptian prisoners as the source of disease.[3] Based on recorded symptoms and analyses of human bones, some scholars suggest the concerned disease was malaria, but others have suggested tularemia, bubonic plague, or smallpox.[4] In fact, it was understood that during the same period there were also outbreaks in Egypt, and some think that the sudden shift of the capital to Amarna, a newly founded city with a purely administrative and ritual purpose, which was abandoned not long after being established, is directly related to an epidemic, in a way helping the elites and the upper bureaucracy to isolate themselves during that period.[5] Based on archaeological data and ancient textual sources, it was claimed that this was actually a regional epidemic that affected most of the Eastern Mediterranean world during this period.[6]

Although some scholars would like to label these outbreaks as the main causes for the collapses of the Sumerian city-states and later the Hittite Empire, the evidence implies that there were other reasons like political, economic, and more importantly climatic events, to which the states and the people could not quickly adapt, which resulted with the weakening of the systems and their final collapse. In any case, epidemics were one of the main causes of socio-political and economic disruptions and resulted with change in positive or negative ways.

Today we know the mechanisms of how bacterial and viral infections spread and affect our bodies, and we try to avoid contamination with physical distancing and with an adequate level of hygiene. However, many still would like to believe that epidemics are linked to some sort of divine intervention, like in ancient times. Besides being a result of certain ideas that belief systems dictate and in some cases being an outcome of old superstitions, I think this is also a sign of guilt as people are well aware to what extent we have damaged the ecosystem of our planet and feel that the current neoliberal capitalist system, which is exploiting and devouring the planet’s resources and all beings inhabiting it, is not sustainable. The connection between the human-imposed climate crisis and the pandemic seems to be strong and makes us all think that the global socio-economic system cannot continue to exist in the way it used to function.[7]

İstikal Caddesi these days.

It is now the end of spring and the weather is beautiful. As we approach the end of our fellowship period at ANAMED, İstiklal Caddesi is getting more and more crowded, with many shops opening after two long months. People hope that things will get back to “normal” and this nightmare will be something of the past, but many studies predict something different. The Covid-19 pandemic most probably will not cause systems to collapse but, considering the level of distrust it has resulted with, we are surely to witness drastic changes and will be living in a very different world after it is over. Unfortunately, whether this will be a better world or a darker version of what we currently have is something hard to guess in this time of uncertainties.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

[1] Mujais, S. 1999. “The Future of the Realm: Medicine and Divination in Ancient Syro-Mesopotamia” American Journal of Nephrology 19: 133-39; Bácskay, A. 2017. “The Natural and Supernatural Aspects of Fever in Mesopotamian Medical Texts” in S. Bhayro and C. Rider, eds. Demons and Illness from Antiquity to the Early-Modern Period. Brill: Leiden, 39-52.

[2] Niazi, A.D. 2014. “Plague Epidemic in Sumerian Empire, Mesopotamia, 4000 Years Ago” TheIraqi Postgraduate Medical Journal 13(1): 85-90.

[3] Singer, I. 2002. Hittite Prayers. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature; Pritchard, J.B. 1955. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (ANET), ANET 395.Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[4] Smith-Guzmán, N.E., J.C. Rose and K. Kuckens. 2016. “Beyond the Differential Diagnosis: New Approaches to the Bioarchaeology of the Hittite Plague” in M.K. Zuckerman and D.L. Martin, eds. New Directions in Biocultural Anthropology. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, 295-316.

[5] Kozloff, A.P. 2006. Bubonic Plague in the Reign of Amenhotep III? KMT-A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt 17(3): 36–46.

[6] Gestoso-Singer, G. 2017. Beyond Amarna: The “Hand of Nergal” and the Plague in the Levant. Ugarit-Forschungen 48: 223-48.

[7] Lorentzen, H.F, T. Benfield, S. Stisen and C. Rahbek. 2020. “COVID-19 is Possibly a Consequence of the Anthropogenic Biodiversity Crisis and Climate Changes” DanishMedical Journal 67(5): A205025.