Reconstructions are a valuable tool for better understanding and visualizing the past. While archaeological evidence is often incomplete and takes many disparate forms—ranging from artifacts in museums to the results of chemical analyses—reconstructions allow for a more complete picture of the places, objects, and people that made the ancient world so vibrant. Reconstructions also enable an understanding of the history of an object or place, compressing the centuries or millennia between the past and present into a cohesive narrative.

For many people, the first type of reconstruction that might come to mind is that of archaeological sites. One famous example in western Anatolia is the reconstructed façade of the Library of Celsus at Ephesus. Other types of reconstructions range from drawings and videos to physical constructions that are used for experimental archaeology. The development of digital technologies also facilitates new avenues for archaeological reconstruction. For example, “The Curious Case of Çatalhöyük” exhibit—which was presented in the ANAMED gallery from June 2017 to February 2018—included an immersive virtual reconstruction that allowed visitors to experience what a Neolithic building might have looked like while it was in use.

The Istanbul Archaeology Museum has made extensive use of reconstruction during its recent renovations. Galleries are decorated with scenes such as a Mycenaean wanax (king) holding court in his throne room or Osman Hamdi Bey and his team removing sarcophagi from the necropolis of Sidon. Reconstructions are especially prevalent in the Troy gallery and its associated exhibit on archaeological methods and are used to tell multiple intersecting stories about the site and about the history of archaeological research in Anatolia.

Reconstructing Excavation

The history of excavation at Troy is referenced throughout the exhibit, along with information on a variety of archaeological methods. This presentation of archaeology at the Museum employs multiple types of reconstruction.

The most prominent is a representation of the site’s stratigraphy that dominates the center of the exhibit hall. This model and its associated text teach visitors about the study of stratigraphy—the layers of sediment, stone, artifacts, etc. that accumulate over time and allow us to reconstruct the phases of a site’s history—which is one of the foundational concepts of scientific archaeology. Simultaneously, the uneven lighting that leaves parts of the model in shadow gives it an almost mystical quality.

Figure 2. The impressive model of a stratigraphic section from Troy has an immediate impact on a visitor to the gallery (photo by author).

In a back room of the gallery, an exhibit on archaeological methods also makes extensive use of reconstruction. As one enters, the left side of the room is dominated by a reconstruction of an excavation area, combining a physical model on the floor with a video of actors carrying out day-to-day activities. The room further includes a viewing area for a video that shows the stages of excavating an object and preparing it for display in a museum, as well as scientific dating methods including carbon-14 and dendrochronology (a dating method based on tree rings). In a time where pop culture depictions of archaeology are often sensationalized or disparaging, reconstructions that show the realities of archaeological work are especially valuable.

Reconstructing Troy

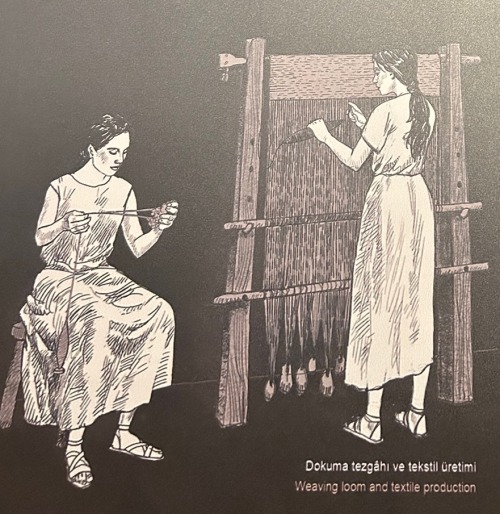

Elsewhere in the Troy gallery, displays of objects from the site are accompanied by artistic depictions of people using those objects in furnished spaces. These reconstructions, which include elements like wooden looms and woven rugs, remind us of the objects in our lives that often don’t survive in the archaeological record. Alongside these images are scale models of specific complexes; though these scale models are empty of people and objects, they provide a more striking image of the architecture at the site than is presented in traditional plans.

Figure 3. A reconstruction of women spinning yarn and weaving on a vertical loom (photo by author).

Figure 4. A scale model of a house from Troy I (c. 2920–2550 BCE) (photo by author).

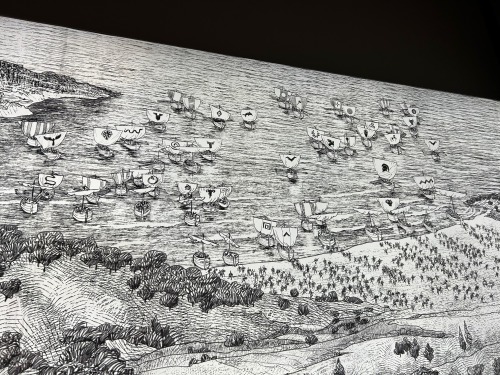

Reconstructing the past is not without risk, however. Visual media are a particularly powerful way of communicating information. Thus, a reconstruction can obscure the distinction between evidence and inference and leave visitors with a mistaken impression of its subject. In the Troy gallery, some of the displays and reconstructions lean heavily on the myth of the Trojan War, in which the city was besieged and sacked by a Greek army led by mythological heroes like Agamemnon and Achilles. For example, an impressive audio-visual reconstruction of Troy’s occupation phases depicts the Trojan War as the cause of the site’s destruction at the end of the Late Bronze Age (though it is unclear if the evidence supports this interpretation). A large reconstruction of the landscape around ancient Troy—ostensibly based on evidence from archaeological excavation and embedded within the part of the gallery focused on scientific archaeology—also depicts this landscape as under attack.

This myth is certainly an important part of the site’s history, as it shaped the campaigns of early explorers, including that of Heinrich Schliemann, who is remembered as the man who rediscovered Troy. However, by embedding the myth of the Trojan War into the narrative of the exhibit and into reconstructions of the past, the Museum obscures over a century of scholarly debate over the historicity of this event and the complex political history of Bronze Age Anatolia.

Figure 5. Photos of a reconstruction of the ancient Trojan landscape. A close-up highlights the inclusion of attacking Greeks (photo by author).

Figure 5. Photos of a reconstruction of the ancient Trojan landscape. A close-up highlights the inclusion of attacking Greeks (photo by author).

Reconstructing Dispossession

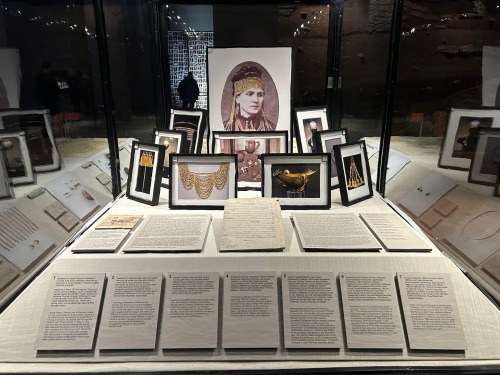

A final narrative that I want to explore is found in a single display case near the beginning of the exhibit. This area, which describes the mythology around Troy and its centuries-long history of exploration and excavation, visually refers to museums of the past with display cases of wood and warped glass and text made to look like newspaper headlines. One of these cases is dedicated to telling the story of “Priam’s Treasure,” a hoard of gold jewelry and other artifacts excavated at Troy by Heinrich Schliemann in 1873. Schliemann’s focus on mythological history led to his original conclusion that this treasure belonged to “the period of the Trojan War,” though later study revealed that it dates much earlier.

Figure 6. A display case with photos of objects from “Priam’s Treasure” that are held in other museums. At the center is a famous photo of Schliemann’s wife, Sophia, wearing items from the treasure (photo by author).

The display tells the story of how the treasure was smuggled out of the Ottoman Empire and how it moved between museums throughout Europe until it arrived in its current home in the Pushkin Museum in Russia in 1995. The absence of most of these artifacts is emphasized by a few of the objects that have been successfully returned to Turkey; meanwhile, the collection and its journey have been reconstructed using photographs, maps, and text. Other museums include similar exhibits that emphasize the loss of cultural heritage, such as the Acropolis Museum in Athens that uses plaster casts to remind viewers of the Parthenon Marbles that were removed from the country and remain in the British Museum today. (See also this video on the museum website that traces particular marbles around the globe.)

Research on provenance—where an object came from, its history of ownership, and the ways it may have been damaged, altered, or repaired over time—is important for understanding the authenticity and legality of museum collections. However, this research also highlights the unethical or illegal ways that many cultural heritage objects have been removed from their original contexts.

Archaeological reconstructions are often imperfect and not without bias; it is wise to approach them with a healthy amount of skepticism. That said, they remain a valuable tool for interpreting our past—both ancient and recent—and bringing it to life today.