Ketty, doktorasına başlamadan önce Bologna Üniversitesi’nden Kültürel Miras alanında lisans, Klasik Arkeoloji alanında yüksek lisans ve Klasik Arkeoloji alanında uzmanlık derecesi almıştır. Dr.Iannantuono ayrıca birçok uluslararası arkeolojik projeye katılmış ve Radboud Universiteit, Vrije Universiteit ve Universiteit van Amsterdam’da Eskiçağ Tarihi ve Arkeolojisi alanında çeşitli akademik dersler vermiştir.

KHI ve ANAMED’deyken, iki güç arasındaki savaşın patlak vermesinden sadece bir yıl önce, 1910’da Ankara’da arkeolojik misyonun gerçekleştirilmesini mümkün kılan İtalyan ve Osmanlı ajanları arasındaki akademik ve diplomatik ilişkileri araştırmayı planlamaktadır.

Archaeology on the Threshold of the Italian-Turkish War: The 1909–1910 Italian Archaeological Mission at the Temple of Augustus and Roma in Ankara

Ketty Iannantuono

Introduction

In the last half-century, archaeology has endured a major phase of self-criticism that has shaken the foundational epistemologies of the discipline. This ongoing “loss of innocence” is turning archaeology into a self-critical practice.[1] From this perspective, the growing number of studies dedicated to the history of the discipline is particularly significant.[2] Thanks to such studies, we have gradually begun to recognize archaeology as a process deeply influenced by the changing aims of its practitioners, who are, in turn, deeply affected by contemporary scholarly, social, and political agendas. Research undertaken on the history of archaeological activities conducted by “Western” actors in “non-Western” settings, in particular, has shed light on the major role played by archaeology in establishing forms of cultural, political, and socio-economic control.[3] Despite such ferment, the path to decolonizing archaeology is still a long one.

The project I am conducting as a joint fellow at the Kunsthistorisches Instituut in Florenz and the Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations follows this path. Specifically, my project aims at better understanding the ideological ties of early twentieth-century Italian archaeological activities in the eastern Mediterranean by looking at one archaeological mission conducted by Italians in Anatolia, at Ancyra, modern-day Ankara, in the years 1909–1910.

Focus

The 1909–1910 Italian archaeological mission at Ankara emerges as particularly striking when considered against the background of the scientific relevance of its outcome, its ideological scopes, and the existing Mediterranean geopolitics.

First, the mission held great scholarly relevance. Its aim was the production of a 1:1 plaster-cast copy of the temple dedicated to the emperor Augustus and the goddess Roma at Ankara. Such reproductions were coveted by epigraphists from all over the world: the walls of the pronaos of the temple were inscribed with the best-preserved attestation in Latin and Greek of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, the “queen of inscriptions”—as it was defined by the father of modern epigraphy, Theodore Mommsen. Visited and variously documented since the mid-sixteenth century, the Monumentum Ancyranum became an object of scientific interest by the mid-nineteenth century, when multiple archaeological missions were launched at the site.[4]

Second, the plaster cast produced by the 1909–1910 mission was meant to be exhibited in a particularly ideologized vitrine: the Mostra Archeologica, an archaeological exhibition organized on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the unification of Italy in 1911.[5]

Third, the Mostra Archeologica was permeated by the rhetoric of Romanità—the myth of ancient Rome and its dominion over the Mare Nostrum as an alleged justification for contemporary Italian colonialism. Times could not have been more mature. In September 1911, the Italo-Turkish war broke out in the Mediterranean.

The questions driving my investigation of the 1909–1910 mission are the following: Who were the people involved in the archaeological campaign? Which institutions participated? How did the diplomatic network between Italian and Ottoman agents function? What were the outcomes of the campaign? How were these outcomes presented to different audiences? What were Italian and Ottoman reactions?

Research activities

So far, my explorations have included the mining of various historical, diplomatic, and photographic archives. During my research stay in Italy, I have focused my attention on the Archives of the Museo Nazionale Romano, the Museo della Civiltà Romana, the Archivio Centrale dello Stato, the Archivio Storico Diplomatico della Farnesina (Italian Ministery of Foreign Affairs), the Archivio Storico Capitolino (Municipality of Rome), the Istituto Centrale per il Catalogo e la Documentazione, and the Istituto LVCE in Rome. In Florence, I investigated the Photothek of the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz, the archive of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Firenze, and the photographical archives of Fratelli Alinari.

Besides visiting archives, during my stay in Florence, I benefited greatly from the use of the library of the KHI, where I found a highly stimulating but also relaxed environment in which to conduct research. There, I could closely study documents such as the official catalog of the Mostra Archeologica and the Rassegna Illustrata dell’Esposizione di Roma del 1911, a popular Italian periodical that was published during the entire life of the exhibition and that offers much information about the display of the reconstruction of the temple and about its reception by the audience. Other great sources for my investigations have been contemporary publications concerning the exhibition, such as Italian and international reviews of it; for example, the extensive review by Eugènie Sellers Strong—at that time, vice-director of the British School in Rome. Furthermore, the catalogs of the Museo dell’Impero, the Mostra Augustea della Romanità, and the Museo della Civiltà Romana have been useful to trace the aftermath of the copy of the temple (after the end of the Mostra Archeologica, the plaster cast from Ankara moved across the collections of these museums). Scholarly publications related to the temple and to the Res Gestae that appeared just after the Italian campaign at Ankara have also been analyzed as sources of relevant information about the reception of the Italian mission at Ankara and of its results by the scientific community.

During my research stay in Turkey, I had the occasion to consult archival materials preserved at the Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi (Ottoman State Archives) in Istanbul and Ankara. Furthermore, I explored the archives of the ex-Italian Embassy at Istanbul preserved at Palazzo Venezia (today’s Italian consulate) and at SALT Research Archives. In Istanbul, the libraries of ANAMED, the Netherlands Institute in Turkey, the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, the Institut Français d’Études Anatoliennes, and the Istituto Italiano di Cultura have been fundamental assets for my research. In Ankara, I investigated the archive and library of the Türk Tarih Kurumu (Turkish Historical Society). A short stay at the British Institute in Ankara has allowed me to better investigate travel notes, archaeological reports, and historical photographs taken by various scholars passing through Ankara and visiting the temple between the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century, such as John Henry Haynes and John Garstang. Together with the study of the reports by Georges Perrot and Edmund Guillame, Andreas Mordtmann and Carl Humann, the analysis of the work by these scholars has helped me to better contextualize the Italian 1909–1910 mission within the history of scientific attention paid to this site. Thanks to a special permit granted by the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara, I could enter the temple of Augustus and Roma and produce photographic documentation of its current state of preservation.

In terms of scientific collaborations, my stay in Turkey has been particularly rewarding. In particular, I could get in contact with many local experts who have helped me in reading and interpreting Ottoman documents, getting in touch with local museums and archives, and looking at my research topic from a different perspective. A special note of thanks is here due to Prof. Dr. Edhem Eldem, Prof. Ufuk Serin, and Dr. Artemis Papatheodoru.

Preliminary results and prospects of research

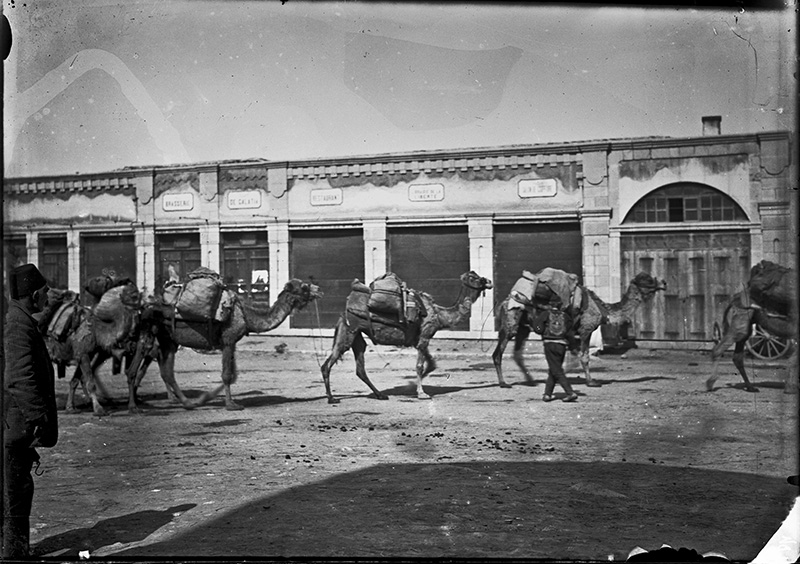

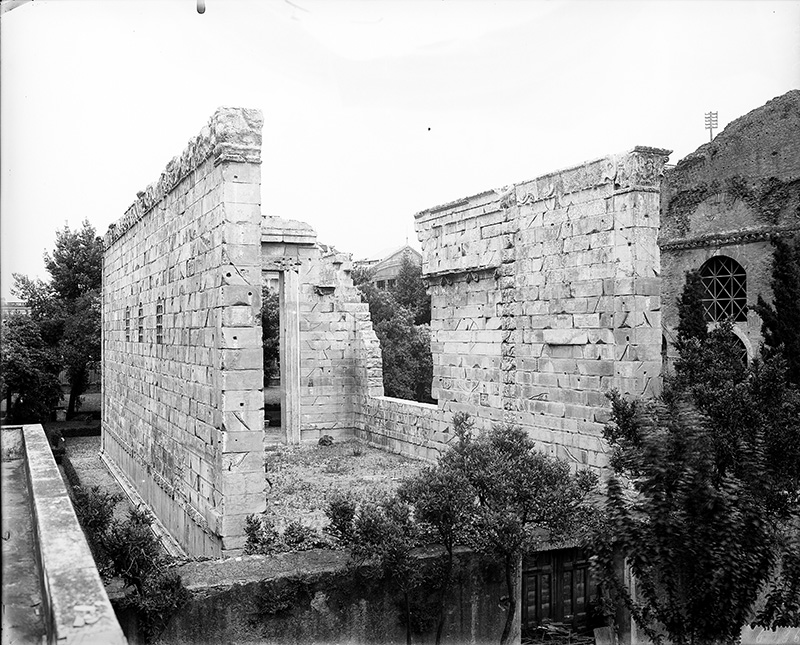

One of the most relevant results of my research so far has been the identification of an unpublished group of 45 photographs produced during the 1909–1910 Italian mission at Ankara. Such photographs were preserved uncatalogued in the archives of the Museo Nazionale Romano. They mostly reproduce architectonic details of the temple, documenting the presence of local housing on the site. Some of the photographs also capture general views of the city, while others attest to the archaeological campaign and the probable involvement of local people (see, e.g., Fig. 1). Unfortunately, no written working notes, diaries, and/or travel reports from the campaign seem to have been preserved. On the other hand, the photographs taken in situ are accompanied by—scare—metadata. Further photographic documentation of the temple prior to and after the Italian archaeological mission and of its reconstruction as exhibited at the Mostra Archeologica, the Mostra Augustea della Romanità, and the Museo della Civiltà Romana has been retrieved in various archives (see, e.g., Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. The Italian mission departing for Ankara. Asia Minor, 1909, unknown photographer. Photo courtesy of the Museo Nazionale Romano archives.

Fig. 1. The Italian mission departing for Ankara. Asia Minor, 1909, unknown photographer. Photo courtesy of the Museo Nazionale Romano archives.

Fig. 2. Reconstruction of the temple of Augustus and Roma at Ankara as displayed in the courtyard of the Baths of Diocletian during the Mostra Archeologica. Gelatin silver print, Rome, 1911. Photographer: Carlo Carboni. ICCD, C006936. Photo courtesy of Istituto Centrale per la Documentazione e il Catalogo.

Fig. 2. Reconstruction of the temple of Augustus and Roma at Ankara as displayed in the courtyard of the Baths of Diocletian during the Mostra Archeologica. Gelatin silver print, Rome, 1911. Photographer: Carlo Carboni. ICCD, C006936. Photo courtesy of Istituto Centrale per la Documentazione e il Catalogo.

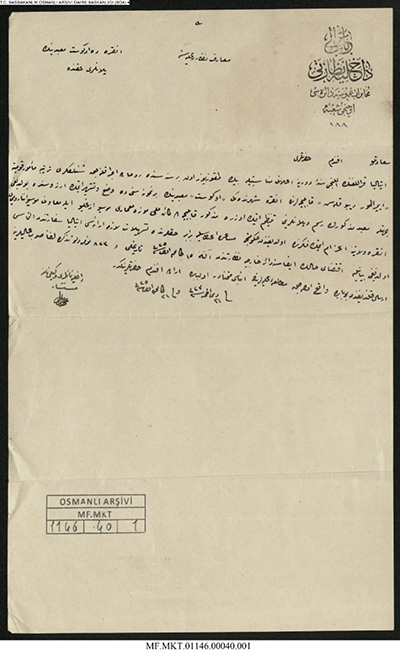

The permits granted to the Italian mission in order to perform archaeological activities at the temple were preserved at the Ottoman State Archives in Istanbul (see, e.g., Fig. 3). Such documents—also unpublished—are interesting for the reconstruction of the Italian-Ottoman diplomatic network that enabled the mission, as much as for the analysis of contemporary Ottoman policies in cultural heritage management.[6]

Fig. 3. Permit granted to the 1909–1910 Italian mission at the temple of Augustus and Roma at Ankara by the Ottoman State. Photo courtesy of the Osmanlı Arşivi.

The scientific outcomes of my research are informing a scientific article currently in preparation. Furthermore, the retrieved archival and photographic documents will be made available via a virtual exhibition about the mission and its protagonists. Finally, the study of the 1909–1910 Italian mission at Ankara will constitute a first pilot case study for the development of a larger project about the history of early twentieth century Italian archaeology in the eastern Mediterranean that I am currently developing.

Stay tuned!

Works cited

Bahrani, Z., Z. Çelik, and E. Eldem, eds. Scramble for the Past: A Story of Archaeology in the Ottoman Empire. Istanbul: SALT, 2011.

Barbanera, M. L’archeologia degli italiani : storia, metodi e orientamenti dell’archeologia classica in Italia. Rome: Editori riuniti, 1998.

Casson, S. Progress of Archaeology. London: McGraw, 1934.

Ceram, C. W. Götter, Gräber und Gelehrte: Roman der Archäologie. Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1949.

Clarke, D. “Archaeology: The Loss of Innocence.” Antiquity 47 (1973): 6–18.

Daniel, G. A Hundred Years of Archaeology. London: Gerald Duckworth, 1950.

Díaz-Andreu, Margarita, and T. Champion, eds. Nationalism and Archaeology in Europe. Boulder CO: Westview, 1996.

Kohl, Ph. and C. Fawcett, Politics, and the Practice of Archaeology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Hamilakis, Y. The Nation and its Ruins: Antiquity, Archaeology, and National Imagination in Greece. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Iannantuono, K. “Displaying Plaster Casts, Staging Romanization: The Mostra Archeologica at the Baths of Diocletian and Nationalistic Biases in Roman Provincial Archaeology.” Journal of the History of Collections 34, no. 1 (2022): 95–112.

La Rosa, V. L’Archeologia italiana nel Mediterraneo fino alla Seconda Guerra Mondiale. Catania: Centro di Studi per l’archeologia greca del Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, 1986.

Malone, C., and S. Stoddart. “David Clarke’s ‘Archaeology: The Loss of Innocence’ (1973) 25 Years After.” Antiquity 72 (1998): 676–7.

Marchand, S. “Orientalism as Kulturpolitik: German Archaeology and Cultural Imperialism in Asia Minor.” In Volksgeist as Method and Ethic: Essays on Boasian Ethnography and the German Anthropological Tradition, edited by G. W. Stocking, Jr., 298–336. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996.

Mattingly, D. “From One Colonialism to Another: Imperialism and the Maghreb.” In Roman Imperialism: Post-colonial Perspectives, edited by J. Webster and N. Cooper, 49–70. Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1996.

Meskell, L., ed., Archaeology Under Fire: Nationalism, Politics and Heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. London: Routledge, 1998.

Munzi, M. L’Epica del Ritorno: Archeologia e politica nella Tripolitania Italiana. Rome: L’erma di Bretschneider, 2001.

Schnapp, A. La conquête du passé: aux origines de l’archéologie. Paris: Carré, 1993.

Shaw, T. “West African Archaeology. Colonialism and Nationalism.” In A History of African Archaeology, edited by P. Robertshaw, 205–20. London: James Currey, 1990.

Trigger, B. G. A History of Archaeological Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

[1] According to the archaeologist David Clarke: “In the new era of critical self-consciousness the discipline recognizes that its domain is as much defined by the characteristic forms of its reasoning, the intrinsic nature of its knowledge and information, and its competing theories of concepts and their relationships—as by the elementary specification of raw material, scale of study, and methodology” (David Clarke, “Archaeology: The Loss of Innocence,” Antiquity 47 (1973): 7). On the impact of Clarke’s article, see C. Malone and S. Stoddart, “David Clarke’s ‘Archaeology: The Loss of Innocence’ (1973) 25 Years After,” Antiquity 72 (1998): 676–7.

[2] The first attempts in this direction were the pioneering—though largely romanticizing—works by S. Casson (Progress of Archaeology [London: McGraw, 1934]) and C. W. Ceram (Götter, Gräber und Gelehrte: Roman der Archäologie [Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1949]). See also G. Daniel, A Hundred Years of Archaeology (London: Gerald Duckworth, 1950). Between the late 1980s and the 1990s, with the push of post-colonial studies, a new, more thorough wave of analyses of the history of the discipline arose. See, e.g., B. G. Trigger, A History of Archaeological Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989); A. Schnapp, La conquête du passé: aux origines de l’archéologie (Paris: Carré, 1993); Ph. Kohl and C. Fawcett, Politics, and the Practice of Archaeology (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1995); Margarita Díaz-Andreu and T. Champion, eds., Nationalism and Archaeology in Europe (Boulder CO: Westview, 1996); M. Barbanera, L’archeologia degli italiani : storia, metodi e orientamenti dell’archeologia classica in Italia (Rome: Editori riuniti, 1998); L. Meskell, ed., Archaeology Under Fire: Nationalism, Politics and Heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East (London: Routledge, 1998).

[3] See e.g. V. La Rosa, L’Archeologia italiana nel Mediterraneo fino alla Seconda Guerra Mondiale (Catania: Centro di Studi per l’archeologia greca del Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, 1986); T. Shaw, “West African Archaeology. Colonialism and Nationalism,” in A History of African Archaeology, ed. P. Robertshaw (London: James Currey, 1990), 205–20; D. Mattingly, “From One Colonialism to Another: Imperialism and the Maghreb,” in Roman Imperialism: Post-colonial Perspectives, eds. J. Webster and N. Cooper (Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1996), 49–70; S. Marchand, “Orientalism as Kulturpolitik: German Archaeology and Cultural Imperialism in Asia Minor,” in Volksgeist as Method and Ethic: Essays on Boasian Ethnography and the German Anthropological Tradition, ed. G. W. Stocking, Jr. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996), 298–336; M. Munzi, L’Epica del Ritorno: Archeologia e politica nella Tripolitania Italiana (Rome: L’erma di Bretschneider, 2001); Y. Hamilakis, The Nation and its Ruins: Antiquity, Archaeology, and National Imagination in Greece (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007); Z. Bahrani, Z. Çelik, and E. Eldem, eds., Scramble for the Past: A Story of Archaeology in the Ottoman Empire (Istanbul: SALT, 2011).

[4] A good synthesis of the history of travel and scientific missions at the temple of Augustus and Roma prior to the Italian mission is offered by LCL 152: 334–35.

[5] On the Mostra Archeologica, see, e.g., K. Iannantuono, “Displaying Plaster Casts, Staging Romanization: The Mostra Archeologica at the Baths of Diocletian and Nationalistic Biases in Roman Provincial Archaeology,” Journal of the History of Collections 34, no. 1 (2022): 95–112, with bibliography.

[6] Osmanlı Arşivi MF, MKT 1146, 40.1; DH, MUI 50-2, 5.1–4.