Here is how, in her own words, ANAMED 2015–2016 Fellow Trisha Myers came to ‘embrace the liminal space of Yabancıstan with a smile and a sense of humor.’

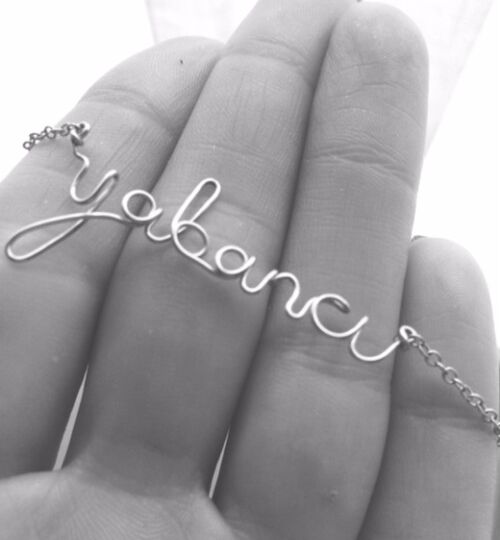

Yabancı [noun]: 1. Stranger, foreigner 2. Foreign, alien.

To be or not to be a yabancı, that is the question you will probably ask yourself at some point if you spend any considerable amount of time in Turkey. Unfortunately, it will likely not be you who decides the answer, but the vast majority of others you interact with on a daily basis. Us, non-Turks, occupy a territory that can be affectionately referred to as Yabancıstan – we are not Turkish, not İstanbullu – we fall under a blanket distinction that is yabancı. Foreigner. Yabancı may as well be a four-letter word to those of us who feel savvy with the language, history, culture, and life of Istanbul. When the yabancı bomb is dropped, you ask yourself, “What did I do wrong? What gave it away? What can I do differently?” You feel bad, you feel like you don’t belong. Walking that liminal line, however, is something you must come to terms with living here.

I’ve been coming to Turkey since 2007. I study Ottoman history, language, and also modern Turkish language. At home I even teach Turkish literature and culture. While I feel decidedly un-foreign in regards to most things Turkish, I will be the first to admit that my modern Turkish capabilities in regard to speaking and conversation can always be improved and in what better way than being in Turkey? Four months into the fellowship, I feel confident in my ability to order food and wine, converse with Carrefour employees, and even make small talk with the employees at Fıccın (the people who know me best). As any good yabancı with a handle on the Turkish language knows, you are confronted with a dichotomy of praise or criticism of just how good that handle is on a daily basis. In a single day I am told that I speak great Turkish by an enthusiastic shopkeeper or a Zara employee who is pleased she doesn’t have to bust out the Tax Free form, but just hours later a waiter will interrupt my order by less than gently explaining that he can speak English. In Sultanahmet, a kind restaurant owner jokingly chastised me for speaking Turkish to him when he messed up my order after we spoke in English together – he mistook “ellilik Efes” for “iced latte.”

There is also a dichotomy of visibility and invisibility experienced by the yabancı, especially in the wild known as İstiklal Caddesi. As a not quite 30-year-old woman, I am used to being the object of many types of attention here. Walking the gauntlet of İstiklal on any given day garners a multitude of reactions ranging from a symphony of clicks signifying disapproval (for what?!) to catcalls and far too prolonged stares that you can’t help but laugh at after enough of them. On the flipside, you’re the lucky recipient of shoulder thrusts, jostling, and complete invisibility if you need help in a shop because, eh, yabancı. My heart even begins to break for the uninitiated yabancılar navigating the non-existent queue formation here. I have found, however, that knowing this pattern can come in handy, especially at the Göç İdaresi where I have successfully defied all queuing logic by elbowing my way to the front unapologetically with the battle cry of “Burası Türkiye.” If that doesn’t earn me an ikamet I don’t know what will.

In sum, you can only embrace this liminal space of Yabancıstan with a smile and a sense of humor because we can also get away with a lot more. For instance, buying beer past 10 p.m. If all else fails, just smile and say, “Anlamadım.” Because we don’t and probably never will.