The Pera Museum houses an outstanding collection of “Anatolian Weights and Measures” formed by Suna and İnan Kıraç. As ANAMED fellows, we were kindly given a guided tour of this collection’s gallery by its Supervisor, Yavuz Selim Güler.[2] Following an elaborate introduction to the agro-economic origins of weights, Güler pointed to the Bronze Age examples, some of which were dexterously shaped as sleeping ducks, frogs, and bulls (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Bronze Age weights in the shape of bulls, frogs, and sleeping ducks (ca. 2000–1000 BCE) in the Anatolian Weights and Measures Gallery.

These weights formed the basis of long-distance trade networks between Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and the Mediterranean for the exchange of resources and luxurious goods. As commodities changed hands, so did precious metals, such as gold and silver. Yet, completing any transaction was a painstaking process: traders had to test gold and silver by touchstones and weigh all the goods using a system of units: shekel, mina (or mana), and talent, corresponding to variously set values of grain and, later, silver.

Figure 3. Hellenistic period weights (third century BCE) in the Anatolian Weights and Measures Gallery.

Visiting this gallery, any careful enthusiast of human history would notice a time jump—to the Hellenistic period (Figure 3)—and wonder about the lack of weights from the earlier part of the first millennium BCE (i.e., the Iron Age). This was exactly my question to Güler in personal communication. His reply that “the situation in the gallery reflects a larger pattern; Iron Age weights are also underrepresented in the archaeological record” was not at all surprising to me as a specialist of this period, because, in these centuries, the world witnessed a major shift: the introduction of coinage and gradual change to monetary economies.

How do we tell the tale of this shift, then? Ancient sources give us some clues. Most commonly cited among them, The Histories of Herodotus (I.94.1) mention that “the Lydians … were the first of men, so far as we know, who struck and used coins of gold and silver; and also they were the first retail-traders.”[3] This reference obviously downplays the role of who came before the Lydians. After all, earlier weight systems, along with ancient tablets listing transactions that were valued in measures of silver, make it quite plain that pre-coinage people had an understanding of the concept of money.

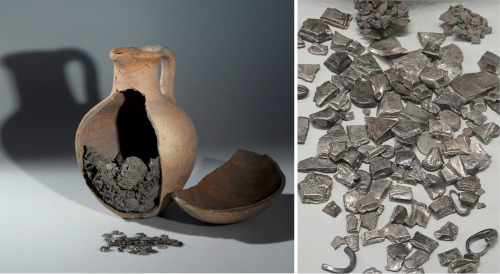

Figure 4. Hacksilber hoard from Tel Dor, after Davis 2021.[4]

A growing body of evidence from Iron Age sites (eleventh–eighth centuries BCE) in the Levant and Syro-Anatolia has started to fill the gap in our understanding of this transition. These sites feature an intriguing class of finds:lumps or cut pieces of silver sealed in juglets (Figure 4) or sacks (of cloth or leather that have now perished). Known by the German term hacksilber,[5] such silver hoards are interpreted as residuals of former dealings. Imagine that a merchant cuts pieces off a silver ingot until its weight is correct for a specific transaction, then collects and weighs leftover silver pieces, packs them in a container, and seals it to guarantee the weight of the silver content, so that they can be used more easily in future transactions. Thus, hacksilber seems to have planted the seeds of the idea behind coinage by speeding up the process of exchange with the use of an official mark of authority, the seal.

Figure 5. An early type of Lydian coin with impressed punches on the reverse and plain striations on the obverse.

Given this long history, why do the Lydians receive the credit as the inventors of coinage? One reason lies in the definition of a coin that sets it apart from any earlier apparatus of payment. Coins were, as they are today, metal pieces with standardized weights whose values were approved by a governing body, and the Lydians seem to have produced coins, by this definition, the earliest.[6] Found in Lydia and its western Anatolian realm of mutual influence (particularly Ionia), these early coins followed the denominational fractions of a specific weight: 14.7 grams, known as the Lydo-Milesian standard.[7] As proof of their authorization, they all had impressed punches on the back (reverse) (Figure 5) and, later, impressed reliefs on the front (obverse), symbolizing the identity of the issuing city and ruling elite.

Figure 6. Gold and silver coins from the Lydian capital, Sardis. © Archaeological Explorations of Sardis.

The Lydians were also rightly acclaimed for being the first to use a bimetallic system in coinage (Figure 6), for their brilliance lay in manipulating the metal contents of their coins. The early generation of coins were struck of electrum, a natural alloy of gold and silver, a.k.a. “white gold.” Despite standardized weights, the metal ratio in these coins varied widely across western Anatolia and the Aegean. Lydian electrum coins, on the contrary, had relatively well-set ratios of 54% gold, 44% silver, and 2% copper—the latter to give coins a more goldish hue. This ratio, unmatched with that of the available natural electrum (73% gold: 27% silver) at the Lydian capital Sardis, demonstrates that they artificially alloyed gold and silver from both local and distant sources to produce their coins.[8] One of the striking consequences of debasing the gold ratio was that people made large profits out of their overvaluation.[9]

Figure 7. A trench in the refinery at Sardis with cupels for silver refining (left) and litharge and foils (right). © Archaeological Explorations of Sardis.

Eventually, Lydians became such experts of these chemical processes that they were able to refine gold and silver out of existing electrum. This process was fabulously documented during the excavations of the “refinery” at Sardis (Figure 7).[10] Later, Lydian kings minted pure silver and gold coins to further control their values. They are known as croeseids (Figure 6), named after the last Lydian king, to whom the English language owes the phrase “rich as Croesus.”

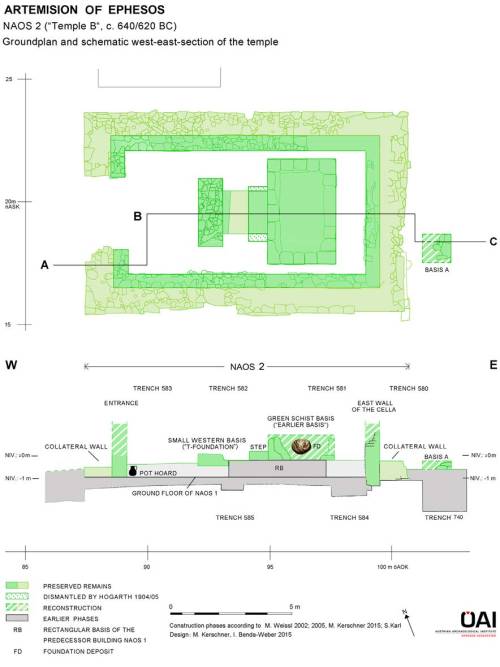

Figure 8. Plan and section of the Naos 2 shrine at the Artemision of Ephesus, after Kerschner and Konuk 2020, 117, fig. 12.

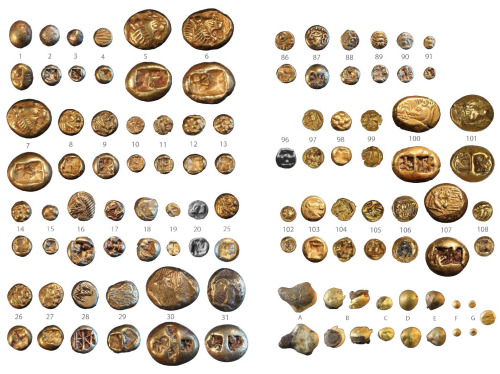

Figure 9. Selected electrum coins from the Artemision of Ephesus, after Kerschner and Konuk 2020, (left) 94, fig. 5, (right) 107, fig. 8.

I keep saying the earliest coins, but how far back in time do they go? Dating early coinage is notoriously difficult, because we rarely find them during excavations in association with other finds and architectural features. They are dispersed around the world in private collections and museums, including renowned ones such as the British Museum and the MET. Most of the time, therefore, numismatists study coins out of their archaeological context, based on comparative weights-denominations, countermarks, style of impressions, die-linking, etc. Exceptions to this exist, however. The earliest group of coins known thus far was dated via their in situ discovery in a very special context: the Artemision of Ephesus. Here, the builders of the second-phase shrine (Naos 2, Figure 8) deposited a jug of coins (Figures 1 and 9) at its foundations, seemingly to consecrate its construction. An excellent recent study of these coins’ archaeological contexts renewed their dating to the third quarter of the seventh century BCE (640–625 BCE).[11]

Figure 10. Electrum coin from the Artemision of Ephesus bearing the KUKALIM insignia associated with the Lydian king Alyattes. © Archaeological Explorations of Sardis.

So, when coins are found in such good contexts, they allow archaeologists to place important developments in time and space but also to scrutinize economic and political relationships. For instance, this Ephesus hoard comprised coins that bear the head of a lion next to the legend “KUKALIM” (Figures 9 (no. 107) and 10). This particular insignia, meaning “I am of Gyges” in the Lydian language, associates their minting with the Lydian king Alyattes, the father of Croesus and a descendant of Gyges, the first king of the Mermnad clan.[12] Another notable hoard of croeseids was found, in context, at Gordion, the capital of the Phrygians. Their date corresponds to the time when the Phrygians came under the rule of Lydia in the earlier sixth century BCE. These discoveries have come to signify the growing power and territories of the Lydian kings.

Figure 11. Nine silver croeseids discovered in 2021 in the palatial complex of Croesus at Sardis. © Archaeological Explorations of Sardis.

At their capital city, Sardis, however, finding Lydian coins in original contexts has been an extremely rare occasion. So, you can imagine how ecstatic we were to add another discovery to the list of only three incidents since 1922[13] during our 2021 field campaign, when nine silver croeseids came out of the ground. Their context is simply superb: on the destruction floor right in front of the monumental limestone terraces that encircled Croesus’ palatial complex, which was entirely burnt and destroyed by the Persians with the rest of the city in 547 BCE. The coins were next to the remains of a male individual, who seems to have possessed the coins in a pouch at the time of his death. Accompanied by a knife next to him and a large number of arrowheads, he must have died defending the king’s palace. After strenuous treatments from Sardis conservators, the coins’ weights matched the known Lydian denominations (1, 1/6, and 1/24), and two of them were of the rarest type: full staters. These coins, given their precise dating, now provide invaluable information for future studies of production technologies, circulation, iconography, and much more.

Figure 12. Animal impressions on coinage of the seventh and early sixth centuries BCE, top left: Miletus, top right 1, 2: Ephesus, bottom left: Phocaea, bottom right: Aegina.

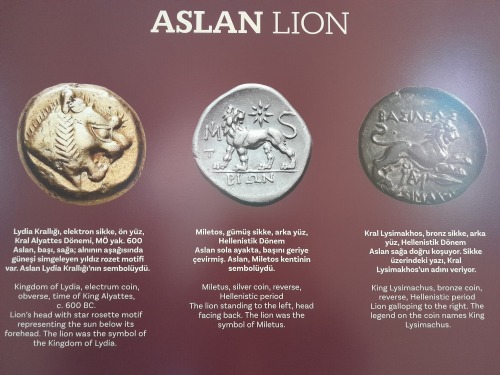

Issued by Croesus, these coins portray a lion facing a bull on the obverse, but Croesus’ use of lion imagery has a deeper history. His ancestors had already borrowed its symbology from the Assyrian world, where it had long been associated with royal power. The same imagery signified the city of Miletus on their early coinage (Figure 12). Though the lion was not the standalone icon—from the onset, we observe the depiction of different animals on coins, with which the issuers echoed their historical-cultural identities: for instance, the stag in Ephesus, a seal in Phocaea, and a tortoise in Aegina (Figure 12).

Figure 13. The entrance to the Fauna and Currency Exhibition at AKMED and the lion poster welcoming visitors.

The choice of animals only diversified through time, and this is the theme of an ongoing exhibition at Koç University’s Suna ve İnan Kıraç Akdeniz Medeniyetleri Araştırma Merkezi (AKMED), Fauna and Currency.[14] Curators Oğuz Tekin and Arif Yacı designed this poster exhibition thematically by the types of animals impressed on currency, from ancient coins to the present day’s paper money. So it is no surprise that, upon entrance to the gallery, the lion poster welcomes you with the image of a Lydian coin (Figure 13). The posters then proceed with various animals of the air, the land, and the sea. A selected few offer a glimpse into their diversity: an eagle, goat, mouse, scorpion, crocodile, hippopotamus, crab, octopus, etc. Two posters advertise each of these animals. One provides brief biological facts and ancient references, while the other flashes the images of animals on currency with their dates and locational information.

Figure 14. Turtle imagery on a fourth century BCE coin from Aegina

In my opinion, these posters do a brilliant job on three accounts. First, explaining the historical and cultural significance of each animal in their own context of currency, the posters help you appreciate how they came to be on monies from significantly different time periods. Second, the printed images of coins magnify their scale remarkably, from their original fingernail-size (and sometimes much smaller) to the size of human head, so they allow you to observe every detail on coins. Finally, their high-quality gives a sense of liveliness, such that you feel you are about to pick up a giant 3-D version of the coin, such as this one from fourth century BCE Aegina (Figure 14).

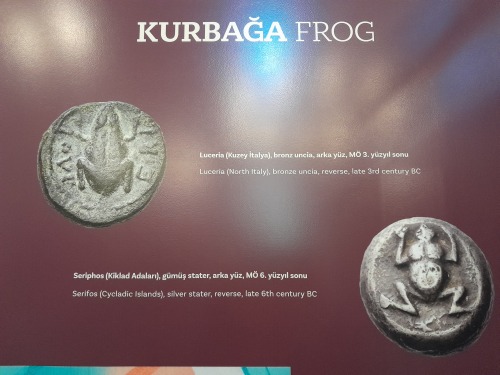

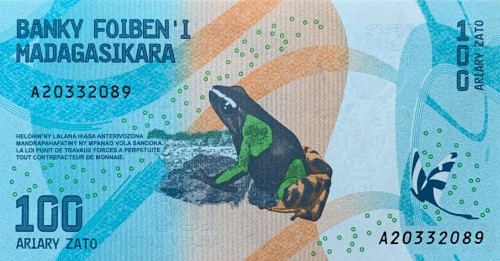

Personally, I enjoyed the millennia-long significance of certain animals that people associated themselves with—for instance the lion, boar, stag, rooster/cock, and horse, which were already embossed on coins of the Ephesus hoard, and the swan and frog that adorned Bronze Age weights, which opened our tale of coinage to today’s money. So, I am leaving you with a few of their images from the gallery (Figures 15–30) to do the same.

Figure 15. Lion imagery on ancient coins.

Figure 16. Lion imagery on ancient Roman coins and on paper money of Tanzania.

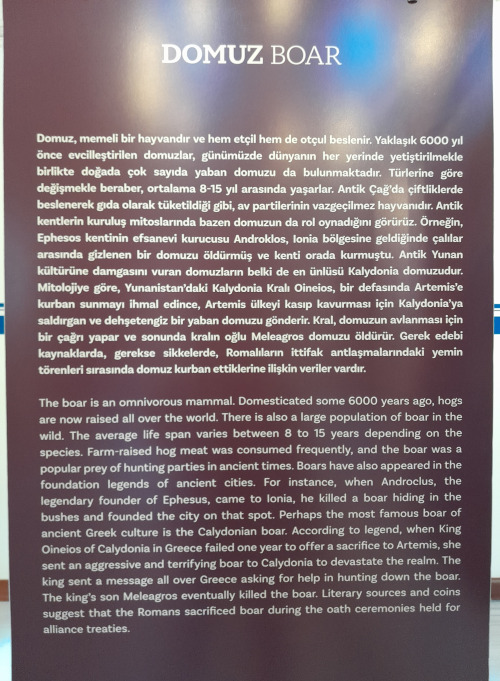

Figure 17. Boar poster in the Fauna and Currency Exhibition at AKMED.

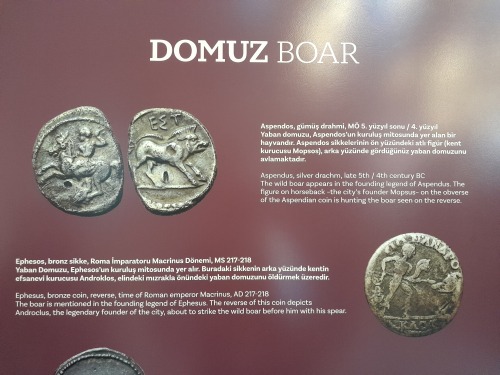

Figure 18. Boar imagery on ancient coins.

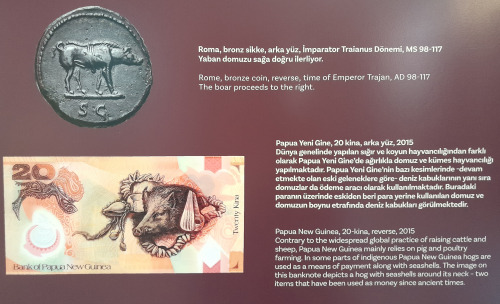

Figure 19. Boar imagery on ancient Roman coin and paper money of Papua New Guinea.

Figure 20. Boar imagery on modern coins.

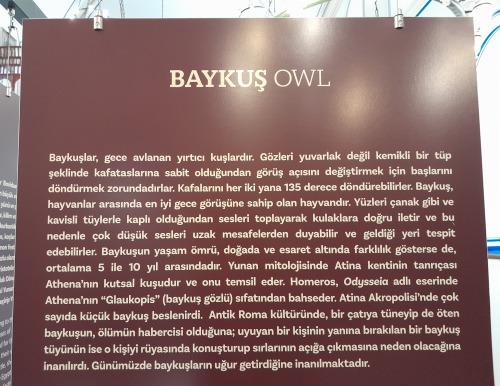

Figure 21. Owl poster in the Fauna and Currency Exhibition at AKMED.

Figure 22. Owl imagery on fifth century BCE Athenian coin and on modern Greek Drahmi and Euro.

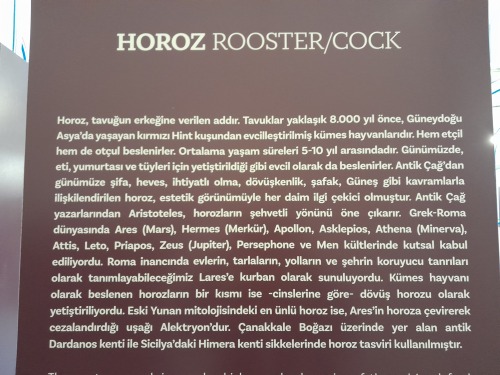

Figure 23. Rooster poster in the Fauna and Currency Exhibition at AKMED.

Figure 24. Rooster imagery on ancient coins.

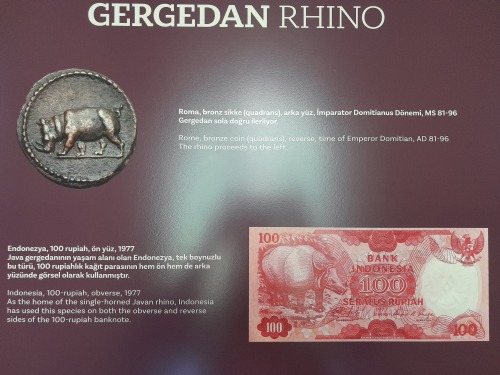

Figure 25. Rhinoceros imagery on ancient and modern currency.

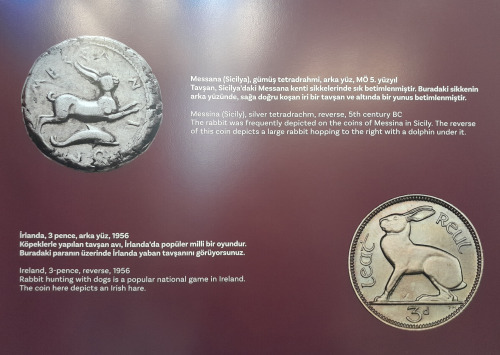

Figure 26. Rabbit poster in the Fauna and Currency Exhibition at AKMED.

Figure 27. Rabbit imagery on ancient and modern coins.

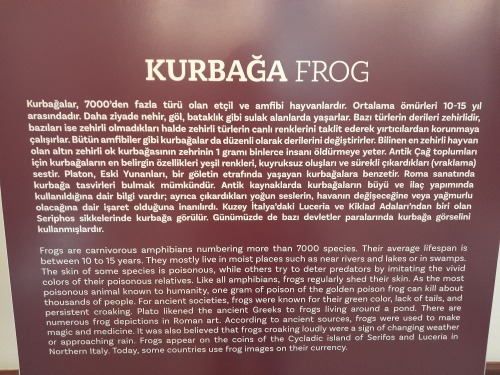

Figure 28. Frog poster in the Fauna and Currency Exhibition at AKMED.

Figure 29. Frog imagery on ancient coins.

Figure 30. Frog imagery on paper money of Madagascar.

————————————————————————————————–

[1] M. Kerschner and K. Konuk, 2020, “Electrum Coins and Their Archaeological Context: The Case of the Artemision of Ephesus,” in White Gold: Studies in Electrum Coinage, eds. P. van Alfen and U. Wartenberg (New York: The American Numismatic Society), 83–190.

[2] On this visit, see also Dr Elisa Galardi’s post on the ANAMED blog.

[3] As the second-century philosopher Pollux discusses early coinage in his Onomasticon (9.3), he refers to Xenophanes of Colophon (ca. 570–478 BCE), who suggested that the Lydians were the first to mint coins, decades before Herodotus did. So the basis of Herodotus’ information may be Xenophanes himself (R. A. Mundell, 2002, “The Birth of Coinage,” Columbia University Department of Economics Discussion Paper Series, Paper #:0102-08.)

[4] G. Davis, 2021, “The Rise of Silver Coinage in the Ancient Mediterranean,” The Ancient Near East Today 9, no. 12.

[5] W. Fischer-Bossert, 2018, “Electrum Coinage of the 7th Century B.C,” In Second International Congress on the History of Money and Numismatics in the Mediterranean World, ed. O. Tekin (Antalya: Koç University Suna & İnan Kıraç Akdeniz Medeniyetleri Araştırma Merkezi), 15–23.

[6] U. Wartenberg, 2017, E. Millman, 2015, “The Importance of the Lydian Stater as the World’s First Coin.”

[7] A coin of this specific weight is called a stater. Its fractions are 1/3 (trite, the most common), 1/6 (sixth-stater, hekte), 1/12 (twelfth-stater, hemihekte), and all the way down to 1/96, which weighs only 0.15 grams. However, other standards existed simultaneously; e.g., the standards of Phocaea and Aegina were, respectively (and roughly), 16 and 18 g.

[8] N. D. Cahill, et al., 2020, “Depletion Gilding of Lydian Electrum Coins and the Sources of Lydian Gold,” in White Gold: Studies in Electrum Coinage, eds. P. van Alfen and U. Wartenberg (New York: The American Numismatic Society), 291–336.

[9] J. H. Kroll, 2010, “The Coins of Sardis,” in The Lydians and Their World, ed. N. D. Cahill (Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Yayınları), 143–56;P. van Alfen, 2020, “The Role of “The State” in Early Electrum Coinage,” in White Gold: Studies in Electrum Coinage, eds.P. van Alfen and U. Wartenberg (New York: The American Numismatic Society), 547–67.

[10] A. Ramage and P. Craddock, 2000, King Croesus’ Gold: Excavations at Sardis and the History of Gold Refining (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press); C. H. Greenewalt, Jr. and N. D. Cahill, 2010, “Gold and Silver Refining at Sardis,” in The Lydians and Their World, ed. N. D. Cahill (Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Yayınları), 134–41.

[11] Kerschner and Konuk 2020, ibid.

[12] A. Dale, 2015, “WALWET and KUKALIM. Lydian Coin Legends, Dynastic Succession, and the Chronology of Mermnad Kings,” Kadmos 54 no. ½: 151–66.

[13] These include one hoard with some thirty gold croeseids in a jug (T. L. Shear, 1922, “Sixth Preliminary Report on the American Excavations at Sardes in Asia Minor,” American Journal of Archaeology 26: 389–409), two coins found near the fortification wall within its destruction debris, together with the skeletal remains of a soldier, apparently a casualty of the city’s sack by the Persians (N. D. Cahill and J. H. Kroll, 2005, “New Archaic Coin Finds at Sardis,” American Journal of Archaeology 109: 589–617), and three more coins on the Acropolis from a Persian looter’s trench of perhaps a cultic building dedicated to Artemis (N. D. Cahill, et al. 2020, ibid.).

[14] I had a chance to see this exhibition during a short research trip to Antalya, thanks to the kind support of ANAMED. Thanks also go to my colleague and friend Assoc. Prof. Erkan Dündar for his gracious hospitality during this trip.