Three incidents came to mind whilst reading Ali Ekrem Bolayır’s 1916 poem Lisân-ı Osmânî.

First. Not long ago, I was stopped by a pair of interviewers talking to passers-by for a Turkish-language learning YouTube series. “Is it possible to live in Istanbul as a foreigner without knowing Turkish?” “Böyle bir yabancıyım,” I joked, and we talked for a few minutes about life in Kadıköy, my work here, and my own process of learning Turkish.

The answer they were expecting for their question was clear enough, and it fit my own past experience, anyway: to live in Istanbul without Turkish, as a monolingual English-speaker, is doable but dissatisfying, limiting one’s social life to an expatriate circle that gets very stale quite fast. But I sensed, even then, the bitter edge to their question. Of course, there are many, many who live in Istanbul without much Turkish, and they do so because they live here precariously; under threat of deportation, of being driven one night to the border, or because they expect one day to transit to their next destination. If there is a question of “possibility” here, it is not one rooted in individual effort but in systematic barriers. A Somali restaurant has its sign defaced for “not being Turkish,” even as Burger King, Starbucks, and Pizza Hut remain sacrosanct. And there is also the historic fact that—once upon a time—one very well could have lived in Istanbul as a Greek-speaker, an Armenian-speaker, French, Ladino, Romany, Arabic, Kurdish, or Persian, without the question of “possibility” entering one’s mind: a fact claimed by revanchists and nostalgics alike, although testifying only to the necessarily political conditions by which things are made to seem possible or not.

Second. There is a friend of mine—one of those slightly maddening friends that make life worthwhile. And he has that sort of facility with languages which makes one alternately awed and envious. Not that it comes easily, without work. Many times, I have seen him with his stack of worksheets and grammar textbooks in the library, talking to strangers, going to classes, getting in his daily practice in French, Spanish, Arabic, Persian, and so on. He lives in Istanbul now and has set his skills to Turkish. Here, he has encountered a problem, he says. In his lessons, when he does not know well the colloquial Turkish word for a term, he will reach for his archive of Arabic or Persian: words that he knows, correctly, were once in Ottoman. He gives the example of cimri, “stingy,” for which he instead used the older word hasis. And the result, he says, are teachers who throw up their hands like the alafranga dandy Bihruz in Araba Sevdası and proclaim “Çince mi bunlar?” [“Are these Chinese?”] One teacher was so aggravated that she was led, in very Bihruz-like fashion, to declaring even ihtilaf [“dispute”] a “non-Turkish word” and unintelligible to her. Of course, we can sympathize with her: tasked with teaching basic Turkish, she was suddenly confronted with an endless, expansive vocabulary of every word which once graced an Ottoman theological treatise, the divan of an eighteenth-century poet, the tales of a meddah. Yet her response—to declare these all simply “non-Turkish”—is striking. It seems unlikely, to me, that she would have reacted with the same exasperation had he simply said “stingy”for cimri instead of hasis. It is the uncanniness of these words, then, that provokes: the way that they tug at memory, at the edge of mishearing, words encountered once or twice on a page in a Tanzimat-era novel read halfheartedly in high school. Spoken aloud, they are both vaguely familiar and utterly foreign. The classroom requires, of course, all things to be clear; yet isn’t it precisely these disconcerting, ambiguous words (the teacher would say belirsiz, my friend, müphem) that give language its poetry, its capaciousness, and color?

Third. On my walks through Kadıköy, I often encounter those kinds of shops which seem both totally singular and totally of-a-type: the stores that only sell one specific, hip product, like tiramisu, San Sebastian cheesecake, vegan sashimi, or handmade, artisanal çiğ köfte. Invariably, on weekends, one must wait two hours or four to sit at a spot which offers only one kind of photogenic croissant. Among these stores, however, one in particular caught my eye: a glass-fronted, pastel-toned boutique called the Güzel Kelimeler Dükkânı [The Beautiful Words Shop]. It doesn’t really sell beautiful words, of course, but pillows, shirts, notebooks, mugs, and other items emblazoned with them in large, elegant serif typeface: nâzende, ciğerpare, tahayyül, tebessüm, ümitvar, hayalperest. I had earlier seen quite a few people in hayalperest t-shirts, and the mystery of their origins was thus solved. But, at the same time, I became rather curious about the criteria by which words were deemed beautiful; a notebook with tebessüm [smile] printed across it is rather sweet, I think, but to wrap myself in a towel labeled müptela [addict], mâlumâtfürüş [pedant], or merdümgîriz [misanthrope] is somewhat less becoming. Even hayalperest, intended here to mean visionary or daydreamer, does not really capture the full connotations of perestarî, which (while generally positive) refers in Ottoman to an intense, abject sort of desire: see putperest [idolator], hodperest [egoist], meyperest [drunkard], or şehvetperest [debauchee], or its erotic forms, gulâmperest and zanperest (the derivatives of which, kulampara and zampara, persist in contemporary Turkish). Instead, the criteria which seems to make these words beautiful is precisely the fact of their loss, regardless of their original meaning or use. An aesthetic, certainly; a commodification of nostalgia, perhaps, although one could argue that the late nineteenth-century writers of Servet-i Fünûn tendency [referring to The Wealth of Sciences, a literary and aesthetic gazette] were doing much the same when they scoured their old dictionaries for striking turns of phrase like havf-i siyâh [black terror] and leyâl-i girîzân [fleeing nights]. Still, it is strange to note the evident contrast between the aestheticization and display of such words in daily life and the simultaneous rejection of them as “not really Turkish.” Indeed, one day I noticed on my aforementioned friend’s shelf a book sold at the Güzel Kelimeler Dükkânı, Lûgat365, containing one “beautiful word” for each day of the year: a wonderful coffee table accessory, of course, but one which I am sure was meant to give some other poor language teacher a sense of havf-i siyâh.

As for Lisân-ı Osmânî [The Ottoman Language]:Ali Ekrem (1867–1937), who wrote this poem in 1914 and published it two years later, was among those Servet-i Fünûn writers addicted to Redhouse, to Lehçe-i Osmani, Kamus-i Türki, and the other etymologies and dictionaries available at the turn of the twentieth century. The authors and poets of his generation wrote in the shadow of earlier, heroic figures like Namık Kemal, who, as the literary historian Jale Parla notes, served as the symbolic fathers in the literary realms that they, largely, brought into being; Ali Ekrem had the additional symbolic burden of actually being Namık Kemal’s son. It is not that he fled from this heritage—indeed, he wrote a nazire [parallel poem] to his father’s famous Hürriyet Kasidesi [Ode to Liberty], several biographies of his life, and helped to republish his letters and writings—but there is a sense that his life and career always existed in an uneasy tension with a more illustrious past. He was often discussed in the press merely as “Namık Kemal’in Oğlu,” even in his obituary—and this description was hardly meant to be flattering to the son. Ali Ekrem’s long bureaucratic and academic career naturally drew comparison with the radical romanticism of his father, and his own attempts at similarly rousing, patriotic verse are belied—at least in my reading—by his palpable elitism and preference for the status quo. But it was in the realm of poetic theory and language that Ali Ekrem struck out a more independent path. Whereas Namık Kemal had championed simplicity and verisimilitude in literature and condemned the influence of Persianate “exaggeration” and “artificiality” upon the Ottoman language, Ali Ekrem, like many of the other writers for the Servet-i Fünûn gazette, worked to revive and adapt long-disused Persian and Arabic words and compounds in order to concoct an aesthetic language which, in its expansiveness and conceptual subtlety, could accurately convey the shifting states of consciousness and affect. In the novel Mâi ve Siyah [The Blue and the Black], Halit Ziya puts the linguistic aspirations of this movement in the words of the struggling poet Ahmet Cemil:

Such a language that…to what should I compare it, I don’t know?… Let it be as eloquent as a theologian’s soul, a translator of all our fates, all our thoughts, all our joys, the many subtleties of the heart, the thousand depths of the mind, our thrills, our fits of pique and caprice; a language that can think and sink together with us into the many shades of despair, a language that can cry and mourn together with our souls. A language that can rage alongside us, in our nervousness and excitement […] A language… Oh! You will think I’m talking nonsense, a language almost as if it is fully human.[1]

In essence, the Servet-i Fünûn group sought to create a completely personal, completely “human” language by blasting apart language’s borders, its limits, and its body of received grammatical forms and tropes. To accurately communicate the variegated, individual self—and we should remember here that these writers were largely positivists, believing such a thing to be eminently possible—meant to scour their etymologies and encyclopedias for forgotten words and turns of phrase that, in their foreign familiarity, could depict the jarring nature of the unbared soul and, ultimately, to craft a new language and literature out of these building blocks. Although Ali Ekrem would later break with the Servet-i Fünûn group over an internal dispute, he remained committed to its essential project and among its staunchest defenders well into the Republic.

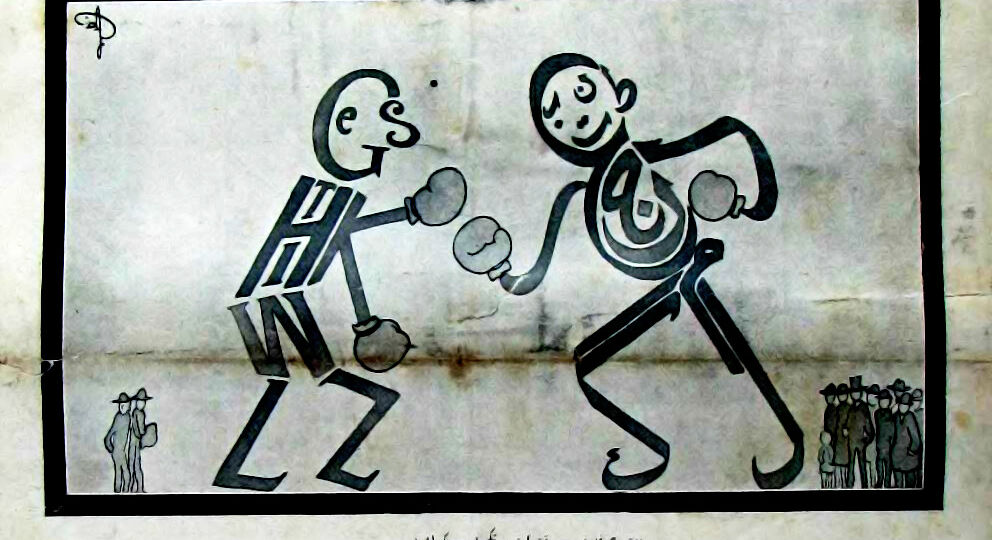

Lisân-ı Osmânî is perhaps his most forthright apologetic in this regard: a short verse treatise dedicated to the elder poet Abdülhak Hamit but composed in direct response to the provocations of another, younger author: the leading ideologue of the so-called “Young Pens,” Ömer Seyfettin. In manifestos like 1911’s “New Language,” Seyfettin attacked the “artificial,” “unnatural,” and “sick” state of Ottoman Turkish under Persianate influence and the “even more distasteful and meaningless salon literature” of the Servet-i Fünun authors. For Seyfettin, as for likeminded figures such as Ziya Gökalp, the notion of such an expansive, composite language was something freakish and bizarre, which had severed the realms of writing and speech and the culture of the elite from the vitality of the masses. For Gökalp, the prospect of conceiving Ottoman as a “language,” as such, was simply “impossible”—an adjective he did not use in quite the same way as Andrea Moro’s 2016 study Impossible Languages but which for him had similar connotations of something fundamentally irreconcilable with normative human psychology and sociality. Writers like Ali Ekrem had only exacerbated this problem: they had abandoned the search for what Seyfettin called language’s “stable ground”—that is, the correspondence between logos and ethnos—in favor of a language based upon nothing, a floating and endless realm of atomized words with no fixed reference point or social base. In the 1914 article “Turkish Against Palace Language,” Seyfettin directly criticized Ali Ekrem’s poetry, writing “what is this language? Who can write literature in a language that nobody speaks?” He summed it up simply: “nobody can call this ‘Turkish’.” Already, Ali Ekrem was composing Lisân-ı Osmânî as his response. It would eventually be published as a chapbook in 1916. The poem begins by recounting and adapting the verses of the great poets of the Ottoman past: Fuzuli, Nef’i, Nedim, Recaizade Mahmud Ekrem, Tevfik Fikret, Abdülhak Hamit, and, of course, his father. Yet it then switches to address Seyfettin directly:

If you can, then, write in full, clear Turkish.

But can you, really? Before such language,

one must go back five, six hundred years,

our language had stalled, and Persian swept us

into captivity; but from Persian

we built a pillar of wisdom, of thought.

We wrote, masters of the Persian manner,

even Yunus Emre fell into Iran.

Persian, too, was worthy of praise and faith,

its spirit steeped in the Quranic tongue.

That is, the soul of our tongue is divine,

our language shines, today, eternally.

Then, from Europe, came civilization,

all the sciences, developed with time,

written with Arabic and Persian words,

and helped to forge a powerful language.

It is said: “write for the nation,” very good!

You vouch for the whole nation, all of us.

The whole nation are farmers, then, villagers?

Today the enlightened youth, rare in their time,

are they not the face of the future, these youth?

Is it right to trade them for the masses?

The youth must be enlightened for their sake,

just as flowers take life from the sunlight.

The political elitism of Ali Ekrem’s position is evident; the latter lines, in particular, drip with condescension. But the shape of his argument is laid out well enough: the capaciousness of Ottoman, its borrowings from other tongues, is not a weakness but a strength. It is what makes the language able to synthesize the immanence of the divine with the epistemology of modern science and is key to its future adaptability. He then moves on to an historicist defense of Arabic and Persian compounds, listing them one by one, as though their beauty and value were innate and obvious:

Shall they say, “big gate” for “Bâb-ı Alî”?

Or shall “Saray-ı Humâyûn” be, to / us, a foreign word? […]

Finally, he criticizes the radical linguistic break advocated by Seyfettin, instead proposing that his “New Language” simply exist as an aesthetic among other aesthetics:

I love this style; you write for the masses.

A bare tongue with plain melodies… Fine, but

don’t touch this tongue’s sharpness of expression,

don’t touch its harmony, its bravery!

Don’t touch it, else our great works be lost,

as our language ends, so will our future.

To return to the beginning. It is not that the three incidents recounted above weigh in favor of one side or another. Rather they testify, I think, to the ways in which the terms of the argument between Ali Ekrem and Ömer Seyfettin are still with us—how they still structure our relation to language. Does the vitality of language depend upon exclusivity or openness? What are the boundaries, where one language ends and another begins? How does one deal with the heritage of words which have long since lost their old usage, their old contexts, to the point of untranslatability? Etymology, Ali Ekrem might have said, is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake: the drive to sort words by lineage as if they belonged to different species. Yet even as Ali Ekrem’s rhetoric is rooted in a kind of classist contempt for the “masses,” the xenophobic aspect of Ömer Seyfettin’s legacy is also clear. As has been said elsewhere, the use of slang by the poor or a refugee marks them as uneducated, unwilling to assimilate to the norm; the use of slang by an expatriate marks them as fluent. And the embarrassment of the chattering classes at Boğaziçili Türkçesi and plaza dili suggests this anxiety is hardly limited to nativist rhetoric but reflects a broader conception of “real language” as something exceedingly brittle, easily betrayable, quickly lost. Certainly, in the case of minoritarian or indigenous languages threatened by setter colonialism, cultural genocide, and the hegemony of a globalized English, this sense of fragility may be apt; indeed, it may be critical for political mobilization. Yet if the linguistic condition of the twenty-first century is, as scholars like David Gramling and Yasemin Yıldız argue, to be one of “post-monolingualism”—that is, of formerly discrete, spoken languages chopped up and reassembled by the global movements of diaspora and the pervasive effects of online communication—then perhaps Ali Ekrem was rather perceptive in declaring Ottoman, in all its impossibility, as the language of the future. In that case, one may face a choice: to either struggle for a sense of authentic self within an endless realm of possible words and expressions, like Ahmed Cemil from Mâi ve Siyah, or else to throw up one’s hands in despair and confusion like Bihruz. For my part, I’m still stuck on another choice—whether my towel should read hayalperest or merdümgîriz.

————————————————————————————————————————–

[1] Please forgive my rather free translations here and below! Undoubtedly someone more skilled would be able to better capture the sense whilst losing less of the form.