The 2020–21 ANAMED Fellowship proves to be a quite unusual one. Because of the Covid-19 pandemic the facilities at Merkez Han still remain closed, and I am far from Istanbul.

The city must have changed quite a bit since the last time I visited. For one thing, two of its main Byzantine sites, the Hagia Sophia and the Chora Monastery, have been turned into mosques again, after decades of serving as museums. One of the most visible changes accompanying these conversions has been the installation of motorized curtains in front of some of the city’s most important Byzantine mosaics. They now vanish from view for considerable spans of time each day. The ideological symbolism of such acts of removal can hardly be missed.

Turkish politics of course have no monopoly on the removal of images as a form of political or ideological messaging. And these acts are often much more permanent than just hiding a depiction behind a piece of fabric. In Byzantine history, religious images came under attack several times, especially during the Iconoclasm of the 8th and 9th centuries. But even beyond that, the elimination of inconvenient works of art always remained a tool in the political arsenal. The practice of damnatio memoriae might come to mind, which entailed the erasure of names and portraits of disgraced politicians from public monuments. One instance comes to us through the writings of Niketas Choniates. In his account of the reign of Andronikos I Komnenos, the infamous 12th century emperor not only orders the murder of his predecessor’s wife, Maria of Antioch, but also has public paintings of her altered to make her look like a shriveled old hag. Still unsatisfied, he later wants them completely removed or replaced by his own visage. His spiteful triumph over Maria is short-lived, however, as his own violent demise was followed in turn by a similar round of damnatio memoriae.

The fall of Andronikos and his portraits is echoed throughout history in many places. Pharaoh Akhenaten’s radical religious reforms netted him the posthumous defacement of many of his public images. Grūtas Park in Lithuania is populated by the toppled monuments of Communist thinkers and politicians, serving as a stark reminder of the paradigm shift that was the fall of the Soviet Union. Pictures of Saddam Hussein’s collapsing statue on Baghdad’s Firdos Square went around the world in the wake of the Second Persian Gulf War. Just this year Black Lives Matter demonstrations resulted in the defacing and even removal of monuments honoring slave traders, Confederate soldiers, and colonialists throughout North America and Europe.

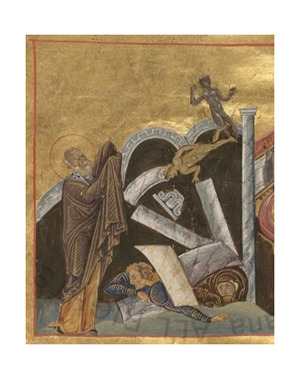

2) Saint Cornelius the Centurion overcomes pagan idols, Vat. Gr. 1613, p. 125

Paradoxically, the erasure of a memorial only works as a statement as long as both the depicted and the destroyed depiction remain part of collective memory. As the depicted transforms into something that is overcome by society, the destruction of the depiction becomes a symbol for this overcoming. To reinforce this, acts of iconoclasm are often turned into powerful images themselves. The toppling of pagan idols was a standard component of Byzantine saintly iconography. More recently Daesh widely disseminated videos of the destruction of cultural artifacts through its online propaganda.

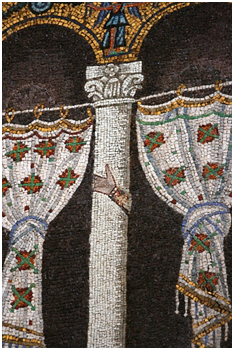

Understanding this dynamic might also help to explain why many acts of damnatio memoriae remained seemingly incomplete. The church of San Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna preserves one such example. It had originally been built as the palatial chapel of the Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great at the beginning of the 6th century. A depiction of his palace can still be seen in a wall mosaic at the western end of the nave. It is an empty palace though, with just lonely curtains swinging between its many columns. Only closer inspection reveals that this cannot always have been the case. On many of the columns one may spy a disembodied hand or an arm. These once belonged to the Gothic courtiers inhabiting the palace, their ghostlike visages still faintly visible in outline here and there between the columns. The mosaic was altered after the troops of emperor Justinian I conquered Ravenna, and the handover of the formerly Arian church to the Nicaean congregation. Maybe the Byzantine craftsmen left the removal of the palatial figures purposefully unfinished, small reminders of the victories of Roman arms over the Goths and Orthodox Christianity over the heretical Arians. Thereby they turned the image itself into a lasting monument to its own destruction.

3) Detail from the Palace Mosaic in San Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna

4) #GoodbyeLooser tweeted by @paulandstorm showing an altered press photo from Getty Images taken on September 15th, 2017

Modern internet culture is usually a lot more volatile than Byzantine art, but we can find some parallels here as well. On November 6th, 2020, the twitter-account @paulandstorm tweeted a seemingly innocuous picture of a little boy mowing the lawn in front of the White House. More observant viewers might notice some strange shadows, tell-tale signs of image alteration. But it is only knowledge of the unaltered original that gives the image its punch. It once showed none other than US-president Donald Trump, apparently yelling something at the boy. The picture had been taken in 2017, and its comedic potential had soon ensured its wide dissemination through social media. But three years later, just when the reality of Trump’s election loss began to dawn on people, his looming departure from office is most forcefully visualized by having him simply vanish from the picture. Finally, the boy can mow that lawn undisturbed.

Seeing all this, it might seem that image removal always has triumphalist connotations, with the image itself as the defeated other. But art historians must be cautious about interpreting all man-made damage to an image in this way. In some cases, these might even attest to diametrically opposed attitudes. Wandering through Cappadocia one can encounter a wealth of Byzantine paintings, some meticulously restored but many others in rather poor condition. If left unprotected, they are often covered in a layer of soot and bear countless scratches and graffiti. In some cases this damage might have been intended to banish the image’s idolatrous power. In many others, it probably stems from simple indifference towards these works of art. But in still other cases, quite paradoxically, are vestiges of an intense admiration towards the portrayed holy figures: graffiti begging for the protection of the saints, smut from devotional candles placed in front of the holiest icons, accretions of bodily oils built up from adoring hands or lips. Sometimes, devotion proves to be just as destructive as enmity or indifference.

5) Damaged Icon of Christ, Dumbarton Oaks MS 3, BZ.1962.35 fol. 39r; Kathryn Rudy recently suggested it as a possible example for iconophagia (https://twitter.com/katerudy1/status/1309060848585977861)

While these acts of worship have chipped away ever so slightly at the paint of the objects of their veneration, others have come even closer to erasing images entirely. The Dumbarton Oaks Library in Washington, D.C. houses many precious Byzantine manuscripts, among them a book of Psalms and the New Testament with several nicely preserved illuminations. One, however, sticks out: an icon of Christ with severe damage. The damage appears deliberately targeted, because it is focused on surfaces where bare skin was shown. Here the paint has been almost completely removed from the parchment. Because the parchment itself and areas of it not depicting skin remains in pristine condition, it seems unlikely that the damage results from kissing or touching the image. Instead, it might be speculated that we see here the results of iconophagia, the deliberate removal of paint for ingestion. Byzantine sources record several instances in which particles from holy icons were mixed with eucharistic bread and wine or consumed as a remedy against illness. Naturally, it is almost impossible to verify traces of this practice concretely, and one can only wonder how many damaged Byzantine works of art might have received their injuries because of this most intense form of devotion.

In the end the reasons for getting rid of an image can be just as varied as those for making one in the first place. We would therefore be well advised to pay close attention not only to how they were created and what the original intentions of their makers might have been, but also to their afterlives. There can be power in an image—today just as much as in the past—but sometimes even more so in its removal.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

Illustrations

1) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Albert_Pike_Memorial_vandalism_9.jpg

4) https://twitter.com/paulandstorm/status/1324766001376993280

5) https://www.doaks.org/resources/manuscripts-in-the-byzantine-collection/psalter-and-new-testament