Evliya Çelebi, a prolific authority on the 17th-century Ottoman Empire, relates in his Seyâhatnâme or “Book of Travels” a curious notion about fish. It is buried in his retelling of the “Procession of the Guilds” that took place in Istanbul before Sultan Murad IV in 1638. A dispute had arisen between the Fish-Cooks and the Helvacıs, or Sugar-Bakers. It came down to which group would get to promenade in front of the Sultan first, with the Sultan deciding in favor of the latter guild. In Evliya’s retelling, the Sugar-Bakers won their place by arguing that:

“…fish was very unwholesome and an infatuating food. In proof they [the Sugar-Bakers] adduced what happened when … Mohammed Efendi, the author of the Mohammedieh, sent his work in the year 847 (1443) to Balkh and Bukhara. When the doctors of those two towns were told that the author had written it on the seashore shut up in a cave, they decided that he could never have eaten a fish, because a man who eats much fish loses his intellect and never could have compiled so valuable a work…”

Evliya does not tell his audience if he agrees with the Sugar-Bakers’ argument regarding the effects of fish-eating. But as an Istanbulite, when he wasn’t being twirled in the air by the Sultan or playing the tambourine (the Seyâhatnâme is an entertaining book), Evliya certainly must not have missed the opportunity to taste what the rich waters of the Bosphorus had long been offering.

Sometime between the Neolithic and Late Iron Age, people living along the shores of the Bosphorus learned that fish were not only tasty but easy to catch here, and this probably had a lot to do with the real estate. To paraphrase the Roman historian Tacitus on the foundation of the city of Byzantium: location, location, location. The narrow Bosphorus connects the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara, leading to the Aegean, and currents push fish shoals towards the strait’s inlets, especially the Golden Horn. One can easily catch from shore the large and small species of fish that move between these bodies of water.

Catching the bounty of the Golder Horn: fishing with rods for istavrit (horse mackerel) from the Galata Bridge, early November 2019. (A side-note: the fish-sandwich seller boats at the Eminönü end of the bridge were officially ordered closed by the municipality on November 1, but they have defiantly remained open.)

In the 4th century BCE, the residents of Byzantium began to monetize their good fortune by exporting the bounty of the Bosphorus. The city soon earned a reputation throughout the known world for its salted fish sauces made of mackerel and tunny. So strong was the smell of fish guts and flesh being processed into garum that the city smelled like “the armpit of Greece” according to Athenian gossip preserved for prosperity by Stratonicus. Byzantium’s foremost product became such a source of pride (and wealth) that fish—closely resembling tunny—repeatedly appear on the city’s coins until the early 3rd century CE. Along the Theodosian harbor quays, now under the Yenikapı metro station, valuable Bluefin tuna and swordfish were landed and processed until Constantinople’s fall in the 15th century. Visiting the Ottoman Balıkhane (fish market) near today’s Eminönü Square around 1844, the English journalist Charles White notes in Three Years in Constantinople that “The abundance of seafish is remarkable… Providence, in its great bounty, has been more liberal in this respect to the Bosphorus than to any other waters in Europe.”

What makes the waters so rich in biodiversity is the contrast in the Black Sea and Aegean environments and the effects this has on the movement of fish. Through the Bosphorus, the less saline and cooler Black Sea waters flow on the surface into the Sea of Marmara and eventually the Aegean. The more saline and warmer Aegean waters flow in the opposite direction about 15 m below the surface current. Fish species are attracted to the change in salinity and temperature, easily riding the currents and migrating between these waters according to the different stages in their life cycle.

Ancient Greek writers, among them Aristotle and Strabo, understood this migration of shoaling fish and describe in surprisingly accurate detail their annual movements. Tunnies and bonitos enter the Black Sea in the spring, around April, and spend the summer spawning, returning to the Mediterranean in the autumn. Sardines and anchovy generally follow the same pattern. Some fish like chub mackerel enjoy a summer vacation in the Sea of Marmara and return to the Aegean in winter.

The Beṣiktaṣ fish market, late October 2019. Note the small Helva stand at the far right; it seems that the Sugar-Bakers and Fish-Cooks are continuing their 17th-century argument.

So what migratory fish are present along the shores of the Bosphorus during these autumn months? To answer this question “research” visits were undertaken to the fish stalls and meyhanes in Kumkapı (where the old Ottoman fish market was relocated from Eminönü in 1958), Karaköy, Kadıköy, Arnavutköy, and Beṣiktaṣ.

Like ANAMED Fellows, lüfer, or bluefish, appear in Istanbul usually by mid-September. This year, they (the fish) appeared a little later than usual, according to a fish-seller in the Beṣiktaṣ fish market. These can also be sold as çinekop, sarıkanat (smaller in size), and kofana (the largest bluefish), with their distinctive red gills pulled out to demonstrate freshness. Hamsi (anchovies) and istavrit (horse mackerel)—delicious snacks to lüfer and people alike—are also now in the Bosphorus waters and will stay a few months longer. Levrek (sea bass) and sadly small tekir and barbunya (red mullet) are here, too, reaching their peak in October. Fish-sellers in the Karaköy fish market lamented that bonito—the smaller called palamut and larger torik—were not as numerous as last year. These small pelagic fish have had the bad luck to fill the fish-seller’s baskets and land on our plates, but one species is no longer present, at any time of the year: Bluefin tuna, probably the fish whose image once appeared on the coins of Byzantium. That is another story for another time, however.

A fine basket of fishes: levrek (sea bass), barbunya (red mullet) and lüfer (bluefish) at the Beṣiktaṣ fish market, late October 2019.

Perhaps Evliya Çelebi’s retelling of the Sugar-Bakers’ claim that the wise Mohammed Efendi never ate fish lest it affect his intellect can be read as a farce. (The Seyâhatnâme is full of dubious claims, such as Alexander the Great being responsible for creating the Bosphorus.) Perhaps the account was simply meant to illustrate Sultan Murad IV’s questionable personal preference of sugar over fish—a century earlier, Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent had been so fond of anchovies that he had one of his sword handles decorated with a hamsi-motif. Or the story can be interpreted as an Ottoman commentary upon Central Asian geography: fish-loving İstanbullular could only pity the land-locked residents of Balkh and Bukhara who had never tasted the Bosphorus’ marine bounty. Surely, with the prodigious intellectual achievements of the citizens of Byzantium/Constantinople/Istanbul, Evliya’s story can be understood as but a temporary victory of 17th-century propaganda, perpetuated by the city’s jealous Sugar-Bakers over the favored Fish-Cooks.

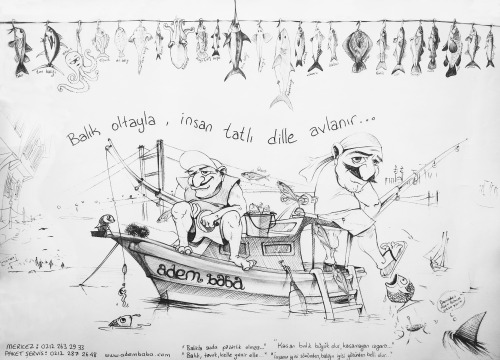

The wonderful placemat from Adem Baba’s restaurant in Arnavutköy. The author of this blog has enjoyed several meals here over the years and hopes it has not affected her intellect.