Dr. Ritter received his PhD in the field of Byzantine Studies in 2017 from Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, and he is a research associate at the same university. His domains of expertise are the political and economic history of Late Antiquity and the Middle Byzantine period. He is the author of Zwischen Glaube und Geld: Zur Ökonomie des byzantinischen Pilgerwesens (4.–12. Jh.) (Mainz: RGZM press, 2019) and has published many articles on Byzantine pilgrimage and travel but also on other research subjects like Byzantine Paphlagonia and Venetian Cyprus.

As part of the DFG-funded project “Procopius and the Language of Buildings,” he prepared the historical component of an interdisciplinary commentary co-authored with Élodie Turquois and Marlena Whiting (forthcoming with Routledge). At ANAMED, he is aiming to extend his research on Justinian’s Constantinople to the subsequent periods until the tenth century by studying the building culture of emperors and the elite in this city in times of turmoil.

Processes of Negotiation in Stone: Building Activity as a Reflection of Social Relations in Middle Byzantine Constantinople (Sixth–Tenth Centuries)

During my time at ANAMED as a Postdoc fellow (2023–2024), I had the precious opportunity to experience key monuments, visit museum collections, access Turkish academic publications not widely available, and—perhaps most importantly—discuss methodology and field observations in a group of Byzantinists and Ottomanists of diverse backgrounds.

All of this contributed to significantly advancing my work throughout the academic year. In the main, I focused on my current book project, the concept of which I will briefly outline in what follows. This book is going to explore the building culture of Byzantine Constantinople after the period of its formation to its acme (sixth–tenth centuries).

Building is a form of utterance of power, as one has to marshal the resources and builders necessary. The completed building is a statement of the credibility and fulfilled ambitions of its patron. In Constantinople, imperial and elite agency met in the field of building activity, as this city was the unchallenged capital across the four centuries of study and was, as the focal point of power in a centralized empire, the primary place of negotiating power among the elites. As a result, the city itself gave rise to a distinctive building culture from the sixth to the tenth centuries. During these troubled times, Constantinople was thoroughly transformed in all its aspects, from its inner topography and visual outlook, to its social and cultural fabric and its identity.

My first aim was and still remains to examine how members of the power and status elites made use of Constantinople with its spaces and traditions for their political agendas. These elite groups, and the emperors above and part of them, redefined, shaped, and appropriated urban spaces. My second mission is to explore the building policy and building culture of the elites as a reflection of their exercise of power. My premise is that the organization and the shaping of urban spaces in Constantinople can be explored through the prism of political relations. In terms of imperial patronage, there is yet no comprehensive study on the building activity initiated by the emperors in the city. Yet it is evident that they treated the image of Constantinople as a tool for conveying power and legitimizing their might, as building continued to be considered a classical imperial virtue.

My study is developed around the premise that the building activities of the elites exerted a great impact on the various parts of the city and entailed negotiations between the elite and the emperor. These processes of negotiation took place, and can be localized, in the various neighborhoods of Constantinople. It is apparent that some building initiatives seem to have more vigorously targeted the people living in a given neighborhood. Questions of spatial hierarchies and nodes are therefore tackled by an investigation and reconstruction of the evolving topography of imperial and elite patronage, based on Byzantine texts and material remains.

My work is obviously grounded in the spatial turn, so I investigate agency over and through space, but I also examine the social embeddedness of the act of building and its processional character. This project closes a gap in scholarship between the fields of architectural, liturgical, and topographical studies by studying processes of negotiation between imperial and elite agencies in the field of building activity in the Byzantine capital.

My evidence derives primarily from historical texts of the period and some documented remains of buildings, as much as they survive. The richness of the written record, including literary genres such as historiography, hagiography, patriography, ekphraseis, and normative texts, allows a fair level of specificity for the study of the building culture. These texts typically emanate from the ruling elites and can thus be taken as mirroring the elite’s view of Constantinopolitan building culture.

Yet, the material evidence, in the form of surviving monuments and excavated remains, is also key for studying the building culture. Just like the texts, the buildings were also overwhelmingly produced for the elites. Worth highlighting is a particularly fascinating aspect of Byzantine building culture during the study period, namely monograms on architectural sculpture. I treasured the chance to access many of them first-hand to compile a comprehensive catalogue which will serve as a basis for one book chapter.

After all, as Istanbul is the arena of my book, I cannot stress enough how great it was to spend nine months in Istanbul. The exploration of the remnants of Constantinople, and especially the in-person surveys of buildings, such as the Fenari İsa Camii or the Bodrum Camii, added a new dimension to my understanding of elite patronage.

Fig. 1. Fenari İsa Camii (Lips Monastery, North Church), small pier in the apse with the ΦΧΦΠ tetragram (φῶς Χριστοῦ φαίνει πᾶσι – the light of Christ elucidates everything).

Additionally, I had the opportunity to visit sites generally not (yet) open to the public, such as Saraçhane/St Polyeuktos, Haydarpaşa, Boukoleon, and the stone collection of the Patriarchate in Fener. I even had the unexpected chance to take part in a field trip to İznik organized by Koç University, which allowed me to more thoroughly explore the hinterland of Constantinople. This also prompted me to later interact with students in the classroom, whose enthusiasm ignited me to push my work even further. Another field trip led me, together with a few other ANAMED fellows, to Upper Mesopotamia (Mardin, Dara, Urfa, Diyarbakir). It was a blast.

Fig. 2. Vaulting of a fortification tower in Nikaia.

Fig. 2. Vaulting of a fortification tower in Nikaia.

In the course of the fellowship, I wrote a paper together with my colleagues M. Dennert and F. Stroth (both Freiburg University) on the processes of spoliation in the Pantokrator Monastery/Zeyrek Camii, which is now prepared to be submitted to a leading scientific journal (as of May 2022). This paper centers around Zeyrek’s minbar from the Ottoman baroque period (late eighteenth century), which constitutes an amalgamation of little-studied Byzantine spolia. The paper, provisionally titled “Deconstructing the Pantokrator: The Minbar of Zeyrek Camii and its Spolia Revisited,” attempts to establish the spolia’s origins and the contexts of its amalgamation in the Pantokrator Monastery/Zeyrek Camii.

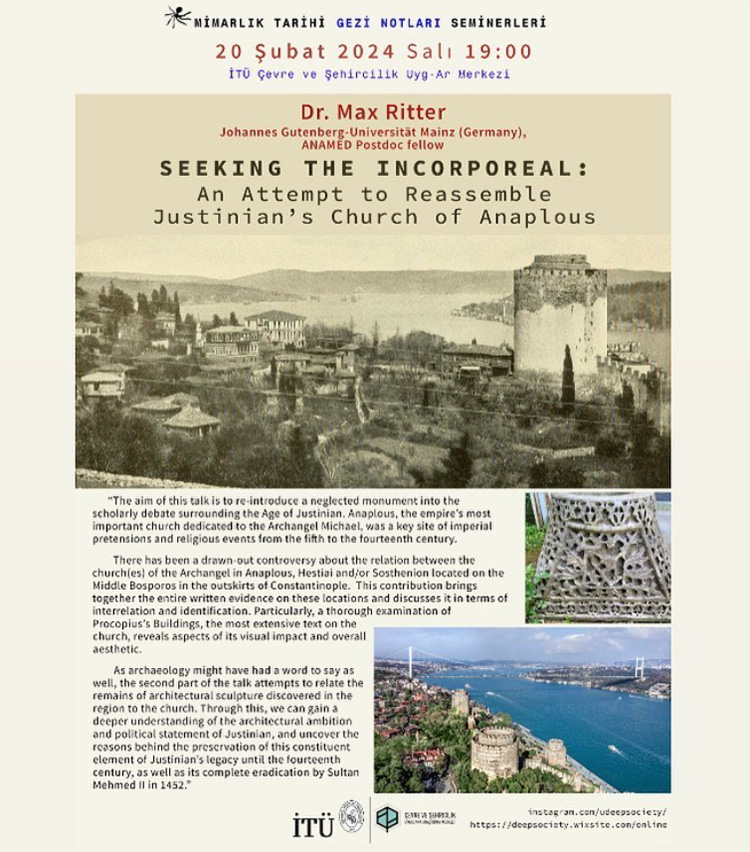

As another part of my work during the fellowship, I have presented on Justinian’s church of Anaplous at the Faculty of Architecture of Istanbul Technical University (İTÜ).

Fig. 3. Announcement of my talk at ITÜ

Fig. 3. Announcement of my talk at ITÜ

This brings me to one of the special benefits which ANAMED provided: the opportunity to discuss in a cross-disciplinary setting with the other fellows and Byzantine scholars based in Istanbul. Thanks to ANAMED, I could expand my personal network to İTÜ, Mimar Sinan University, the German Archaeological Institute, IFEA, Bilkent University and more.

In conclusion, I owe a lot to ANAMED and the people running it. My stay in Istanbul proved to be fruitful and enjoyable and constituted an essential step towards developing my current book project.

See comment above on captions